In my recent series of posts about La Danza de los Santiagueros I demonstrated how the Indians of Mexico had managed to insert hidden meanings into public dance performances. As James Scott explained in his book, Domination and the Arts of Resistance (Yale University Press, 1990, 1-16), it is common for the less powerful in any society to search for ways to safely complain about felt mistreatment by the more powerful; one solution has been to present the grievance in a disguised form. He calls such a disguised complaint a “hidden transcript.” One of the best documented examples of a Mexican dance drama with a hidden transcript is La Danza de los Tastoanes. Although it is usually rare to find detailed explanations of Mexican Indian dances in English, one can learn a great deal about the Tastoanes dance from the books and articles listed at the end of this post.

In light of what I have just written, here is a riddle—”When does a Mexican mask not represent what it appears to be?” The short answer—”frequently.” A slightly more precise answer is— “when it cloaks a hidden transcript.” In la Danza de los Tastoanes the same dancers wear the same masks in a two act performance, yet they probably portray two different groups of characters, one in each act.

Here is a link to a YouTube™ video of the Tastoanes dance:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JdmnpBErj7g

And here is another link, this one about how these leather Tastoane masks are made in Jocotán, Jalisco.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2neuiXeMkE

In this post I will begin with two traditional Tastoanes masks from San Juan Ocotán (Ocotán and Jocotán are neighboring villages), a town in the Municipio (county) of Zapopan, Jalisco, that I obtained from Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazon in 1997 . These are made from leather with attached wooden features and wigs of animal hair. Here is the first of these masks.

This Tastoane mask has the face of a dog. The mask is made of leather, and a carved wooden element provides the dog’s nose and open mouth. This is the standard method for the construction of such masks in villages near Guadalajara such as Jocotán and Ocotán. The hair appears to be horse tail.

Pan Bimbo™ (Bimbo Bread) is a popular brand of mass produced bread in Mexico. On the right side of this mask the dancer has personalized his mask with a small copy of the logo for that bakery, a comic figure wearing a baker’s hat. At the top one sees another such comic element, a pair of footprints.

On the left cheek we find a similar cartoonish design, a mermaid with bubbles and “Berna.” Although I don’t recognize this reference, I suspect that it refers to a soft drink; in Spain, “berna” is the name of a type of lemon.

This view from the back illustrates how a flat piece of leather is folded and stitched together to form the face of the mask. The crown of an old straw hat serves as the point of attachment for several strips of hide that carry the hair.

As you saw if you watched the dance video, Tastoane masks in current use feature the faces of diabolical creatures. The first mask seems so tame in comparison, The next mask goes to another extreme.

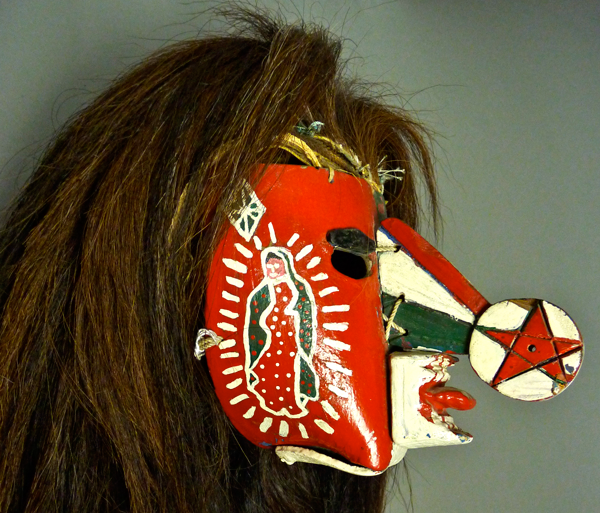

This Tastoane mask is a very classic example of the older style masks, with its stylized nose, decorated with a star, and a second wooden attachment that provides an open mouth with extended tongue.

In remarkable contrast to the current style, this old Tastoane mask has the Virgin of Guadalupe painted on the right cheek.

On the left cheek we find an image of the Virgin of Zapopan, an extremely revered incarnation of the Virgin María in this community. As I will further explain in posts to follow, when Christians portray evil in fiesta dances, they often incorporate religious images to emphasize their distance from the character.

There is another style of leather mask for the Tastoanes dance. One frequently sees these masks labeled as Diablo masks for the Pastorela dance (the Shepherd’d Play). But in La Tierra y el Paraíso (see below for full reference), examples on pages 171 and 201 are labeled as Tastoanes. I believe that this labeling is probably correct, even though the related descriptions in that book tend to sometimes be imprecise, wishful, and overly poetic.

Here is an example of this style of leather Tastoanes mask, from the collection of Helmut Hamm. His was labeled as a Diablo.

Now I want to tell more about the dance. It must already be obvious that there is something strange going on; how could a dance have such extremes of mask designs? I won’t burden you with a lengthy explanation, but for those who are interested, I explained this dance extensively in my book, because it provides such a clear framework for our understanding of Mexican dances in general, demonstrating how a hidden transcript can be the secret driving force for the continuing performance of such a traditional dance. Here is a brief outline.

The dance is performed in two acts—the farsa (farce) and the juego (game). Although the characters in the farce are unchanged in the game, the two acts are as different from one another as day from night. In the farce, Santiago (Saint James the archangel) is pulled from his white stallion by the Tastoanes, who represent “barbarians”. They perform a comic dissection, pretending to remove such organs as the Saint’s liver, heart, and testicles. Abruptly the surgery ends, Santiago stands strong and vigorous, and then in the game he vanquishes the Tastoanes, who now seem to function as infidels or Moors, enemies of Cristendom. Documenting this strange plot, Frances Gilmoor could only shake her head with wonder. Many years later, anthropologist Olga Nájera-Ramírez did fieldwork to uncover the interesting explanation, and I will summarize the local legend that she discovered:

God had elevated Saint James the apostle to the status of a warrior/archangel, but when the Saint fought to support the conquest of the Indians of the Americas by the Spanish, he demonstrated a notable lack of compassion and mercy. Therefore God permitted the Tastoanes to defeat and kill Santiago, as a punishment. Then God restored Santiago’s life and power, but with the injunction that Santiago was to no longer behave as a warrior, instead he was to take up a new career as a sacred healer. This he did, so that now Santiago is greatly loved in such Indian towns as Jocotán.

Books in English about the Tastoanes dance:

de la Peña, Guillermo. “Fiestas de Tastoanes.” in Artes de México #60, Zapopan, published in 2001. Terrific photos with Spanish text are found on pages 54 to 62 and English translation of the text is on pages 79 to 80.

Gillmor, Frances. “Symbolic Representation in Mexican Combat Plays.” In The Power of Symbols: Masks and Masquerades in the Americas, edited by N. Ross Crumrine and Marjorie Halpin, 102–110. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1983.

Nájera-Ramírez, Olga. La Fiesta de los Tastoanes: Critical Encounters in Mexican Festival Performance. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997.

Starr,Frederick. “The Tastoanes”, in Journal of American Folk-Lore, vol xv, num LVII,, 1902. available free from JSTOR at link that follows, navigate with arrows in lower right corner: https://archive.org/stream/jstor-533474/533474#page/n0/mode/2up

And my book (Bryan Stevens—Mexican Masks and Puppets); see Chapter Three—”Dance Complexity in Mexico.”

Earlier I mentioned another important book, which was published in a French edition and a Spanish edition:

La Terre y el Paraíso: Máscaras Mexicanas, published as an exhibition catalogue for a show at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Charleroi, Belgium, in 1993 (and also published in a French edition, LA TERRE ET LE PARADIS : MASQUES MEXICAINS).

Next week I will show a variety of wooden Tastoane masks.

2 comments on “The Tastoanes Dance”