Welcome to Mexican Dance Masks—a website that is devoted to the presentation and discussion of authentic masks from Mexico, along with such related topics as the dances that these masks appear in, associated dance accessories, the carvers, the music, and useful books.

My goal is to establish a database of masks and related objects, a discography, an annotated bibliography, and an atlas. I could simply present you with all this as an already constructed package, but I fear that many readers would find such a bundle of information indigestible. Instead I choose to build this collection of information, one post at a time, adding features as the accumulation of data warrents. I will frequently present material that illustrates the hand of a particular artist; often I will know that artist’s name, sometimes I will simply show a recognizable style. There may be occasions when a visitor will be able to supply the name or village of one of my anonymous favorites, and this will be much appreciated.

A related goal is to serve as an area for the exhibition of good Mexican masks from other collections. You are invited to submit photos and descriptive comments of a mask or dance accessory in your collection, whether the item is well documented or of unknown provenance. You will notice that I make it a point to provide multiple views of an object, to better demonstrate its qualities, and I encourage you to do likewise. I am often surprised to see how much more interesting a mask is, in multiple views, in comparison to its appearance in a simple frontal photograph. In photos that follow, you will have the opportunity to see this for yourself.

Although it is impractical for me to write about everything in my first post, I will just say briefly that this is not a site that is devoted to the artistic qualities of decorative masks. Instead, this site is meant to provide information about authentic dance masks, and one purpose of such information will be to assist you in differentiating between masks that were produced within a culture for ceremonial use versus other masks that have been invented, attributed to invented places, and falsely aged. The entire subject of decorative masks will be explored in depth in later posts (and see related discussion in FAQ).

Among other things, this site is intended to introduce or re-introduce you to my first book about Mexican masks—Mexican Masks and Puppets: Master Carvers of the Sierra de Puebla. This was published by Schiffer Publishing in 2012. If you click on the cover image to the right, you can learn more about that book. There I discuss masks from an area of Mexico that can be called either the Sierra de Puebla or the Totonacapan. The latter is an example of Mexican regional names that refer to the former and sometimes persistent inhabitants of a region. In future posts I will introduce you to others, such as the Huasteca, the Mixteca, and the Tlapaneca. In the book I have provided more detailed explanations of some topics (with references) than will seem practical in these posts. On the other hand, the website format is ideally suited to the presentation of photos, compared to the physical limitations imposed by printed books.

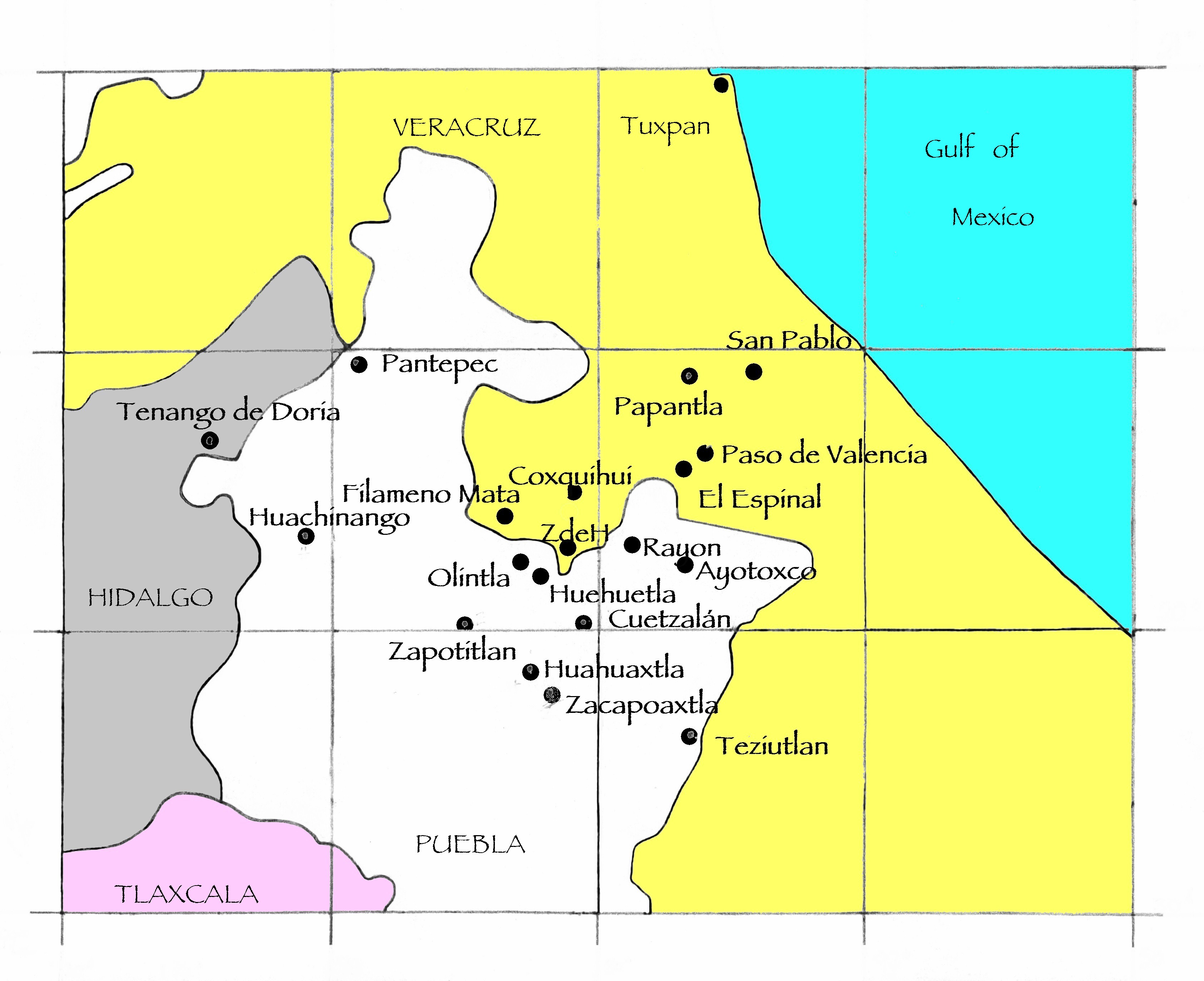

This is my map showing some of the towns in the Mexican states of Puebla and Veracruz where I found masks, dances, and carvers to include in the book.

I am currently writing a second book about masks from Mexico, focusing on Yaqui Pascola masks. I will be sharing some information from that manuscript in future posts.

I am also gathering information for a third book, which will present Mixtec Masks from the Mexican state of Oaxaca, along with some masks from neighboring cultures. My co-author on that book will be Barbara Bruneau Cleaver.

Such a blog has to begin somewhere. I will start with a pair of masks that reflect the early style of an identified master carver—Benito Juárez Figueroa—who lived in various villages in the Mexican states of Puebla and Veracruz. He grew up in Nanacatlán, Puebla, a town just south of Olintla and Huehuetla; in his latter years he lived in Fílameno Mata, across the border in the state of Veracruz. His masks are identifiable due to characteristic details of his carving style. I had featured this carver and his masks in my book.

First I will present a mask that I recently purchased on EBay™. When I first saw it, my attention was immediately drawn to the manner of carving of the ears. It is a strange and wonderful fact that masks with carved ears are the norm in the Sierra de Puebla, and that the mask carvers in this area each develop their own style for carving the ears. Therefore one can often reliably attribute a mask to a particular carver, based on the ear design. In this case, Benito apparently developed his own style as a young man, rather than copying the styles of his father and grandfather, who were established mask carvers. Later he adopted and improved upon his father’s style. Benito was born in 1910, he died in 1994, and I am supposing that the masks with his early ear design date to the first half of the 20th century. I have only seen a few of these masks, but I suspect that more of these will turn up, in museums, in private collections, and on the Internet.

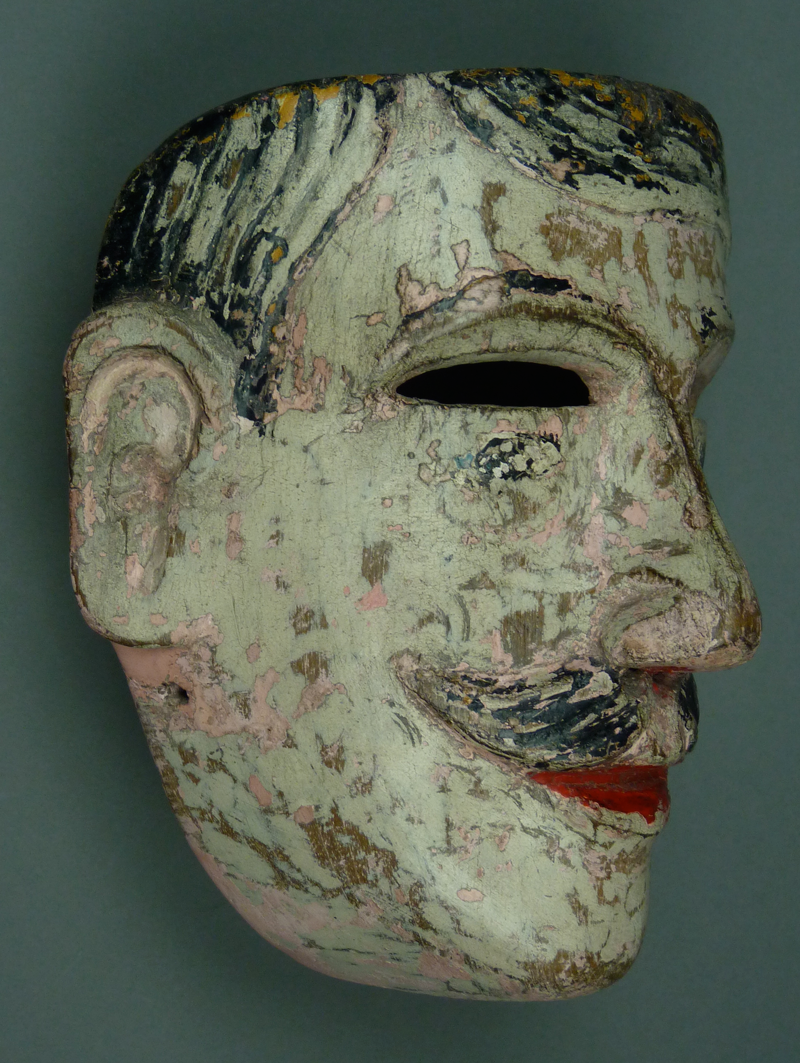

This is the EBay mask of a Tejonero (or Huehue), from La Danza de los Tejoneros (or Huehues). Unfortunately, the paint is worn away, but I want to call your attention to the carved features. Starting from the top, the hair is very carefully carved in relief, with grooves, as is the mustache. As is often the case for this carver, the designs for the brows and the nose are integrated; actually one sees this integration in the masks of many cultures, such as those of the Inuit and the Tarahumara. The eyes were painted but not carved in relief; this carver only occasionally carved the eyes in relief. Below the brows, and over the eyes, we find openings to permit the wearer to see; I call these vision slits. Look how carefully the vision slits are shaped and contoured on this mask. Note the curving planes over the vision slits that sweep down the sides of the nose. Finally, observe the jutting lower lip of the mouth, how it curls. Such details will be more apparent from the side view, as will also be the case for the ears.

From the side, you may be able to see the bulbous nares at the base of the nose, the curling lower lip is more evident, and one is particularly aware of the careful carving of the planes above the vision slit. Of course the main reason that I am showing this view is to demonstrate this very sophisticated ear design, which is unlike any of the styles used by other carvers in this region.

The photograph of the back of this old mask by Benito Juárez Figueroa provides an opportunity to introduce various subjects:

1. Patina or “wear”—When a dancer wears a wooden mask, his face makes close contact with the back in some areas, particularly along the rim of the mask, and less so on the flat back, which has been deliberately recessed to minimize or prevent such contact. After use for several hours, the points of contact become stained by the dancer’s sweat, which contains water, salt, and oils from the skin. Often the dancer will wipe the back with a cloth after use. Over repeated uses, the staining builds up, creating something that I call “sweat varnish.” Because of the variation in contact with the dancer’s skin, the back of the mask will demonstrate differential staining. The presence of differential staining is one test for the authenticity of a danced mask.

2. The back of a mask often presents a stylized form that reflects a regional design. Then, within those parameters, the individual carver will add his own characteristic design details. Benito, for example, has a tendency to hollow out an area in front of the nose, and to bore holes there to aid the dancer’s access to air. He also carves a small flat spot, or “shelf”” that corresponds to the position of the dancer’s mouth. Less commonly he would sometimes create a hollow pocket to hold the knot of the top strap (usually a heavy cord). This last feature is rare for other carvers. As it happened, this mask had not only the characteristic ear design for Benito, along with his characteristic sculpted brows and nose, but also three typical features on the back. By knowing the features of this carver, I am able to make a very positive identification of this mask.

3. There can be an interaction between the patination or staining process that results from the dancer’s sweat with these special features. Note that the hollow for the nose protected the bridge of the dancer’s nose from contact with the wood, as did the hollow spot to accommodate the mouth, so both areas are more lightly stained. The hollow spot for the knot is also less stained. Examination of such details allows one to feel more confident that one is seeing authentic differential staining. That is, the mask market is flooded with masks that have been stained to create a false impression of age. Usually those masks lack differential staining; instead the entire back of the mask is stained uniformly, often to a very dark brown color, or even black.

4. It is not uncommon to find writing on the back of a mask. Usually one sees the dancer’s name, or maybe several names, as if the mask was loaned to one person and then another. In this case the person who collected the mask wrote the name of the dance and the place where it was found—Almolonga, Veracruz. This mask was created in the Totonacapan, but it somehow ended up a hundred miles north, in the Huasteca, a region where the carvers do not ordinarily provide their masks with ears. Pickers and traders spread such objects around.

Next I will add a second mask by the same carver, to demonstrate the consistency of this carver’s style. I purchased this mask from Alina Juárez Pérez, who is the daughter of Benito Juárez Figueroa, in 2008. It introduces a new wrinkle, as this mask was carved to represent a female Tejonero, but the carver’s family later converted it to a male, apparently to please the carver’s grandson, by nailing on a wooden mustache. Such gender change operations are very common in the Totonacapan. One telltale sign is the hairline. In this region, female masks have a hairline that curls past the top of the ears, while male masks often have relief-carved sideburns that extend the hairline down to mid-ear. In this case the hairline was extended with paint alone, not by carving. In contrast, the relief-carved and grooved hair of the previous mask extended down the front of that mask’s ear. Also note that the ears of this mask were originally pierced for earrings, and the hole is still there on the right ear.

Otherwise, you may have already noticed some obvious similarities with the last mask. The combination of brows and nose is very similar, as is the mouth. The eyes are painted, not carved in relief. The ears have the same design.

From the side, one can see the ear very clearly, with its piercing. The delicate carving of the nose is much easier to see on this mask, compared to the last. The shape of the hairline at the ear remains difficult to see, although it is probably easier to see that the right sideburn is not carved in relief.

The back of the second mask is rather darkly stained, all over. This mask does have the same carved hollow for the nose, and that area does demonstrate differential staining. Likewise this mask also has that carved “shelf” below the nose that is typical for this carver.

And here is a third mask in Benito’s early style.

There is an amusing story about this mask. Vernon Kostohryz bought it from a dancer in a remote part of the state of Puebla. It was extremely dirty, so Vernon held it under the faucet in the bathroom sink at his hotel. To his shock, all of the dirt washed off at once, leaving him with this stark white mask with crinkled paint, which had suddenly lost the patina on its face. It did still have terrific patina on the back. In fact, if you compare the back of this mask to the second one in the last post, you will be hard pressed to see any difference between the two. At that time I had not yet discovered the female to male mask that came as the identified work of Benito, and this was just another anonymous mask, waiting to be identified.

The relief carved hairline on this mask is clearly in the female pattern. We see again the integrated design of the brows and nose, along with painted eyes. The ears have the right shape, but the details are obscured by heavy repainting.

Another view of the ear, still not very convincing on its own.

The back of the pale faced female Tejonero mask has all of the features that one could desire to verify that this mask was carved by Benito. We see the hollowed area for the nose, the flattened shelf at the level of the mouth, and the forehead hole for the strap that is recessed.

In conclusion, the general lesson of this post is that it is possible to study the style of an individual carver, permitting one to pick out excellent masks from the weird mixture that is currently offered for sale on the Internet. As you will continue to see in the masks to follow, one spots the work of an individual carver by the idiosyncratic details of his style.

Next week I will say more about this carver, Benito Juárez Figueroa, including a demonstration of the ear design that he typically carved during his later years.

Welcome to my website, and do let me know if there is a subject of particular interest to you.

Bryan Stevens

11 comments on “Welcome To Mexican Dance Masks”