Carnaval (carnival in English), the celebration that we also know as Mardi Gras, occurs each year, on or around Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday. In the Mixtec villages along the Pacific coast of the Mexican state of Oaxaca, these masked fiestas tend to occur over a period of days before Ash Wednesday. This year, as we have often done in the last few decades, my wife Lucy and I traveled to Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca, so that we could travel up the coast to revisit and research these dances. Here is the view from the beach in front of our room in Puerto Escondido.

We could choose between this quiet stretch of ocean, a section of pipeline surf several hundred yards to the viewers left, or a peaceful swimming pool next to our bungalow.

On a low wall behind the swimming pool, the Mexican artist Alejandro Colunga has left a zoology lesson.

During our visit in February the sea was calm. More recently, in early May of this year, the surf became far more dramatic and waves advanced to wash over the street along the beach. A few hardy surfers challenged waves of horrifying size, as you can see in this video.

As always, we stayed in the Hotel Santa Fe, a place that can be counted on to keep us comfortable, rested, and well-fed in the intervals between our exhausting all day forays to the Mixtec villages. This hotel is the creation of our friends, Robin and Barbara Cleaver, and an additional attraction of these visits is that we can share their company. They have been visiting the Mixtec villages since the 1970s.

One must drive two or three hours up the coast, spend several hours more visiting friends there and observing the dances, and then return to Puerto Escondido as night is falling. Usually sundown finds us still on the road, despite our best intentions to leave sufficiently early that we don’t have to drive at night. And why is that? It is common for domestic animals such as horses to stray onto the road; occasionally serious collisions result. We would also like to avoid daily long trips to and fro, but the hotel situation has not advanced to a point where we would want to stay in the villages overnight.

For those who have never been there, here is the place where we were staying.

http://www.hotelsantafe.com.mx/

The area of the Pacific coast that borders the boundary between the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca is known as the Costa Chica, or “Little Coast.” The Mixtec villages lie along the Oaxacan (wa-ha-kin) side of the Costa Chica while the Amusgo villages span the border between the two states. I showed Amusgo masks in my post of November 3, 2014.

Barbara Cleaver and I are in the early stages of writing a book about the masks, dances, and towns of the Costa Chica. During this year’s visit Lucy and I traveled to some of the Mixtec villages with Robin and Barbara. Usually such trips focus on the dances, but this time we spent several days visiting traditional Mixtec carvers.

On the first day we visited members of a famous family of carvers from the town of Pinotepa Nacional. In an earlier post, on August 18, 2014, I introduced you to the late Filiberto López Ortiz, a carver whose great talent was noticed in far-off Mexico City. Donald Cordry had included a photograph of Filiberto and his wife in the book Mexican Masks, along with photos of a few of Filiberto’s brilliant masks. For many years this has been the only publication that provided labeled photos of Filiberto’s masks, although there were unlabeled photos in Ruth Lechuga’s books.

Our first stop was at the house where Filiberto had lived with his wife. Filiberto was killed in a land dispute more than 40 years ago, but his wife continued to live there until her death in 2008. This time we visited their grown children. There we saw an ancient photo from Filiberto’s wedding; the image has suffered greatly from the tropical heat and humidity.

The family has kept some of Filiberto’s masks and other carvings and these illustrate his talent as a sculptor and mask carver. The first one that I will show may be the very best mask by this carver that I have ever seen; it is also his most unusual mask.

Does this mask represent a man or an ape? I do not know the answer.

The bold but yet careful nature of this carving is obvious.

We measured these masks but then we mislaid the paper. Obviously this one is larger than the norm.

The back is smoothly carved as is typical for this carver. There is staining consistent with moderate use. This is apparently a mask that the family kept and used because it was so remarkable.

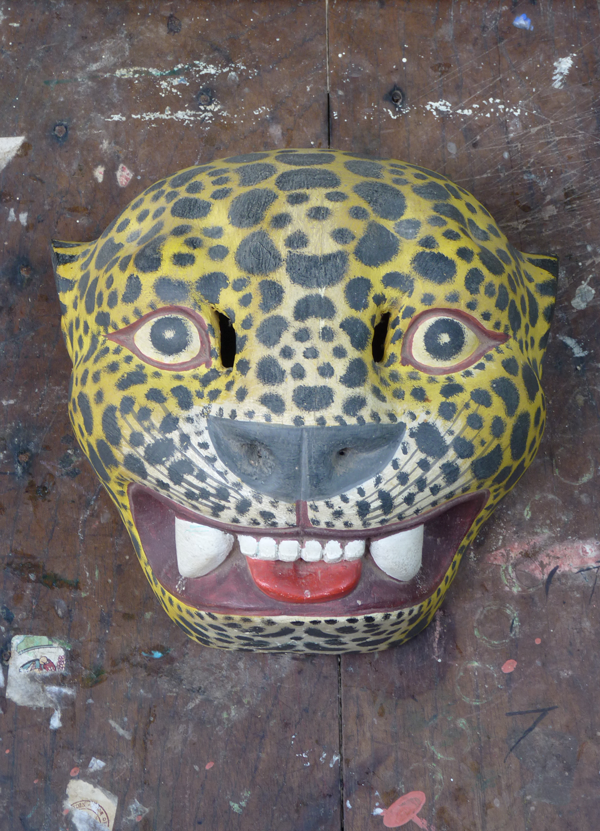

Several masks follow that were carved for use in the dance of the Tejorones. In the Mixtec towns, Tejorones seems to be an umbrella term that refers to a series of masked performances; one finds different variations from one town to the next. In the version that features these masks, there are Negritos (dancers wearing black-faced masks who represent farm or ranch hands), Cuanibuelas (the hacienda owners, wearing Caucasian faces and native clothing), Perros (dogs), and Tigres (dancers wearing Jaguar masks) that threaten the ranchers and the farm animals. First I will show one of Filiberto’s beautiful Tigre masks.

Filiberto had just finished carving this mask when he was killed. His apprentice, Che Luna, painted the mask in Filiberto’s usual style.

These Tigres are justly famous, and much copied by other mask makers in the Mixtec villages.

Seen from any angle, Filiberto’s best masks are carefully shaped so that one feature seems to flow or morph into the next.

As you can see, the back was never smoothed, nor was this mask ever danced.

Filiberto had started to carve another Tigre at the time of his death. This one provides a glimpse of how a master carver plans and executes a mask.

This is guanacaste wood, also called Parota (Enterolobium cyclocarpum). Even at this early stage in the carving one can see the emerging form of a jaguar.

These mask photos were taken on Filiberto’s old and well worn work table.

The back is particularly interesting, because Filiberto has marked the center and then drawn an arc to direct his hollowing efforts. The excellence of his masks reflects the combination of talent and careful planning.

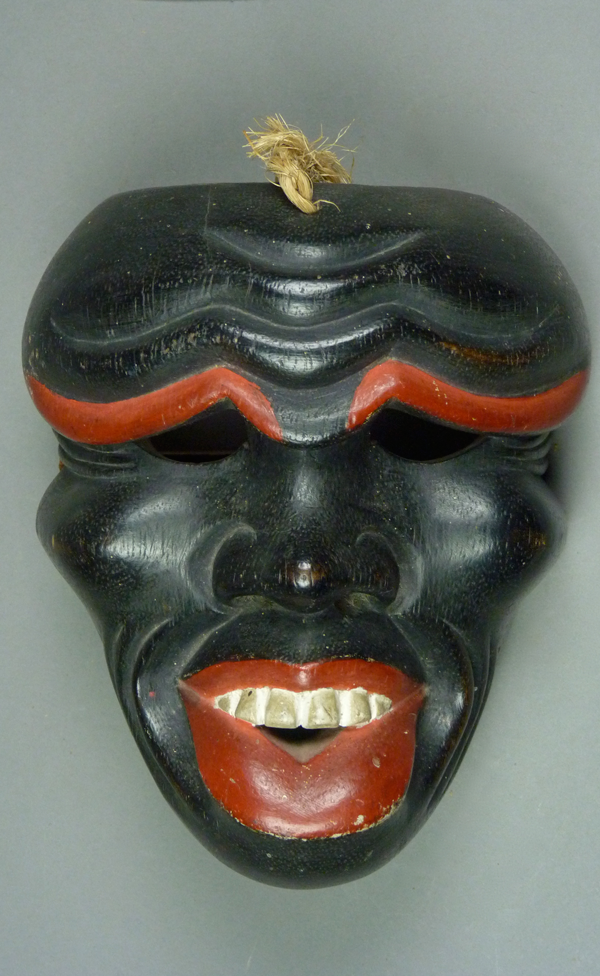

Filiberto and his brother Ladislao (or Lao) were taught by their grandfather to first carve a blank, a shaped slab that can then be marked and further reduced to the desired form. As we have seen, first one carves the face and then one hollows the back. Here is a partly completed Negrito mask by Filiberto, from the family collection, to further illustrate this approach.

If you look carefully at this photo, you may notice that Filiberto marked the tip of the nose on the blank; he had also marked another cross on the half circle over the nose. Then he shaped the face using these reference points. There is a center line coming down over the top of the blank and continuing to the chin.

In this case, Filiberto had only drawn a vertical center line down the back and he had drawn a small circle on that line about 2/3 of the way up from the chin.

This partly carved mask is already attractive. From a sculptural perspective, one might have accepted it as a masterpiece in its present state. But Filiberto was working towards a traditional design. Here I will add photos of an old and worn Negrito mask from my collection to illustrate the form that Filiberto was creating. Although I bought this in Tucson, Arizona as an anonymous mask, both Filiberto’s brother Ladislao and his apprentice, Che Luna, have independently stated that this worn mask was made by Filiberto.

One can see how the initial landmarks on Filiberto’s carving have been carefully shaped and softened. The features are exaggerated and almost grotesque on this example.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6¼ inches wide, and 3¾ inches deep.

The form flows as one turns the mask, although the majesty of this is interrupted by the broken edge of the chin.

The very careful smoothing of the back is one hallmark of a Filiberto mask. The patina indicates extreme wear and long use. This must be a very early mask by this carver.

Here is another example of Filiberto’s very best work. It is from my collection.

It was the rare, wonderful masks carved to this level that brought Filiberto fame in distant Mexico City. The masks in Cordry’s book are carved to this level.

This is spectacular work, no longer folk art, but fine sculpture. It measures 7 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 2¾ inches deep.

As usual Filiberto created smooth contours on the back of this mask.

Here is another mask from the family collection, a Cuanibuela (hacienda owner). This is another that was carved to a very high level.

There are male and female Cuanebuelas. This is the female mask.

I have a nearly identical mask that measures 8 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

As you can see, this mask was finished by Filiberto and subsequently used in dances.

I will complete this account with photos of the head of a processional saint from the family’s collection, an image that was made by Filiberto to be carried in a Roman Catholic procession on religious holidays. I do not know the identity of the saint, but it is undoubtedly meant to portray the Virgin Mary or one of her local representations, such as María Candelaria or the Virgin of Juquila.

Barbara Cleaver’s fingers provide a sense of scale; this is a large head.

I hope that you have enjoyed this introduction to the masks and other carvings of Filiberto López Ortiz. Next week I will tell about our visit to his brother, Ladislao López Ortiz, who continues to carve wonderful masks in the family tradition.

2 comments on “A Trip To The Mixtec Villages of Coastal Oaxaca For Carnaval”