This is the fourth and concluding post in a series that explores and attempts to clarify the boundary between authentic Mexican dance masks and other invented (or “decorative”) masks that pretend to be authentic. This boundary had become dramatically blurred after the publication of Donald Cordry’s book, Mexican Masks, in 1980.

It would be easy to wonder about the value of Donald Cordy’s book—Mexican Masks—after learning that two thirds of the masks can be described as falsely presented (or “decorative”). In the last two posts I called your attention to the fact that the masks that make up the other third are not simply good, but frequently great. Today’s post will identify and examine the decorative masks in this book. For those of you who are joining this blog for the first time, there is a very brief explanation of “decorative” masks in the FAQ section (Question 7), a very detailed discussion in my post of August 4, 2014, and further comments by my friend Charles Thurow in the post of August 20, 2014.

As I noted in earlier posts, any attempt to specify exactly which of these masks is decorative is likely to contain an occasional error. The problem is this—there are so many variations in mask designs and related dances in the villages and towns of Mexico, and so many independent carvers, that no single person can possibly know everything that there is to know about these variations. In recent posts I pointed out instances of disagreement between myself and a very knowledgeable collector, Jaled Muyaes. I noted other instances when the two of us agreed that we didn’t know the status of a particular mask or group of masks.

In spite of this inherent ambiguity, various experts have made some effort to define those masks that are decorative. I introduced their work in my post of August 4, 2014. Despite their writings, which are admittedly in relatively rare, inaccessible, and out of print books, typical decorative masks like those in Cordry’s book continue to show up for sale, for instance on EBay™, with descriptions that suggest that these are authentic and traditional. That is, such masks continue to be falsely presented, despite Ruth Lechuga’s careful explanation in 1988 (in Behind the Mask in Mexico, edited by Janet Esser). This is why I have chosen to tackle this subject on these pages. I believe that the continuing false presentation of these masks has actively discouraged the appreciation of a huge body of remarkable Mexican masks that are traditional, authentic, and meaningful within their respective cultural contexts. Furthermore, this inaccurate labeling tends to discredit the invented masks as well, by inviting us to evaluate them according to specious attributes, rather than on their own merits. Nor do the prospective sellers of these masks benefit, when their erroneous and inflated ideas about the value of these masks frequently prevent the masks from finding buyers, even though there are collectors who appreciate these non-traditional masks as folk art.

In my last post (August 18, 2014) I was pleased to include many photos to illustrate the sort of authentic masks that are found in Mexican Masks. I wish that I could do as much for the decorative masks, but I have actively avoided their collection, so that I have very few of them. Fortunately my friend Charles Thurow, along with his late partner, Dale Hillerman, had chosen to consciously collect masks that we might have called decorative. Despite knowing the true origin of these masks, they nevertheless thought of them as great folk art. Charles has permitted me to photograph masks from their collection, I included some of the traditional masks in my last post, and today I will gratefully present the non-traditional masks, but without false labels.

I want to reiterate that although I will refer to these masks as “decoratives,” we could as readily refer to them as examples of folk art, provided that they were accurately labeled. The problem is that they are falsely labeled in Cordry’s book, whereas the examples that I will include from the Hillerman/Thurow collection will be free of such fiction and fantasy. Therefore in this week’s post I will call each of the mislabeled examples found in Mexican Masks decorative.

It has been an interesting experience for me to revisit the decorative masks in Cordry’s book and to see them through the eyes of Charles Thurow. As I noted in my August 4 post, and as Charles further explained in a special post of August 20, 2014, he prefers to focus on these masks as remarkable artistic creations by individual artists. He is not insensitive to the problematic nature of their labeling and marketing, although he also perceives this aspect as a reflection of the long history of miscommunication and sparring for advantage between indigenous peoples and those of European descent. Equally interesting has been my recognition of patterns within this heterogeneous collection—to essentially observe the unfolding or invention of these masks in a sequence that reflected the interaction between Cordry’s curiousity and the desire of his opportunistic dealers to accommodate him. I can’t say that I know what came first and then what else came next, but rather I can see the breadth of variations that were provided in response to Cordy’s inquiries, and I can see how interesting that process became for Cordry, and potentially for some of us.

In my last post, I discussed the traditional masks in their order of appearance in Cordry’s book, acknowledging the unique nature of each mask. I will approach the decorative masks with a different strategy, grouping them into arbitrary clusters. I am not particularly pleased with this clustering task, as it must sometimes hinge on false ideas or labels instead of the actual mask forms; for the sake of discussion I have to start somewhere.

I. Masks with elaborate curling beards, Moors and Christians, and Archareo Masks

Some of these are the masks that Charles Thurow and Robert Anderson viewed as extensions of the baroque Christian art that was introduced into Mexico in the sixteenth century and others are bearded helmet masks. Here is a list of the masks of this type in Cordry’s book, with his labels and my remarks—

Plate 10 (page 7), “Vaquero, Vaquero Dance, Guerrero.” This mask has an articulated jaw that is connected to the central section of the beard, creating a large swinging panel. Of all the masks in the book, this is one of the strangest.

Plate 16 (13), “Probably for Dance of the Marquez.” This is a good example of the most impressive and beautiful of the Baroque style decorative masks, carefully carved from cedar, and with the misleading appearance of great age and wear. At least five near duplicates appeared in the Celebration of Masks book. I am sorry that I don’t have a good photograph of this type to include here.

Plate 32 (27), “Barbones (Bearded Ones) masks, Dance of the Marquez and others.” These masks have pink faces and elaborate beards. Although dramatic, they are not quite as impressive in appearance as the one in Plate 16, and they are made of zompatle wood, which is lighter, more fragile, and more easily carved than cedar.

Plate 188 (138), “Dwarf Masks, Dance of the Dwarves.” These resemble those in Plate 32, although they have been attributed to another dance.

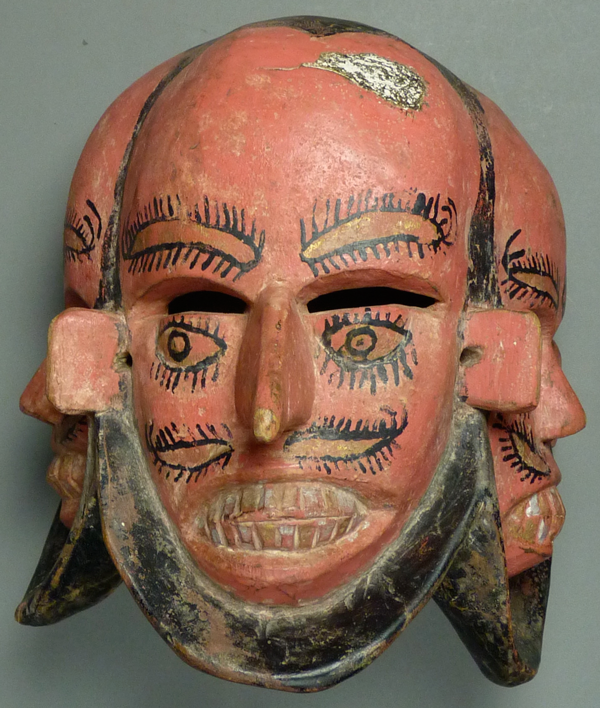

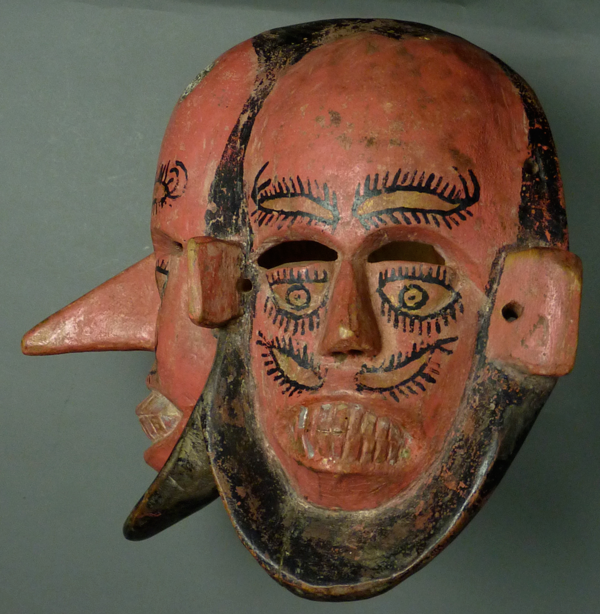

Here is a mask similar to those in Plate 32, from the collection of Charles Thurow. This is certainly a dramatic carving. This particular mask resembles the central statue at the Trevi Fountain, in Rome.

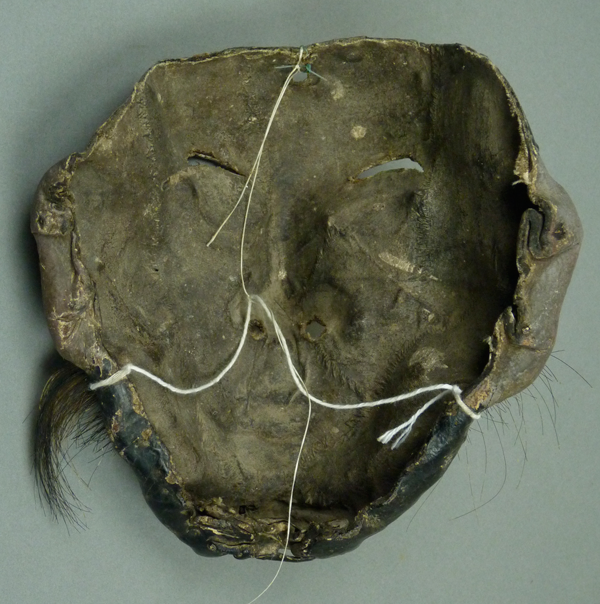

Note that the back of this mask is painted to suggest the inside of a skull.

Here is another mask of this style from the collection of Charles Thurow.

A positive feature about the back of this mask is that it was not falsely aged.

Plate 100 (73), “Probably Emperor Maximilian mask, from Morelos” This is a large mask with an elaborately carved beard.

Plate 138 (98), “Pilate Mask and Sultan Mask,” Plate 282 (230), “Moor Masks” (with painted leather caps), and Plate 286 (233) “Alchileo (or Archareo) masks” are all remarkably similar to one another, almost certainly they were all carved by the same carver. They demonstrate great style, and one feels regret that such masks are not actually appearing in traditional dances.

Plate 139 (99), and Plate 283 (231), are less dramatic versions of this type.

Plates 285(233), “Moro Pasión (Suffering Moor) mask, …Puebla.” This mask lacks a beard, but is attributed to the dance of the Moors and Christians. It appears to be an exaggerated copy of genuine masks that are made and danced in Veracruz. Whereas this mask has a nose that almost endlessly spirals, the authentic versions have upturned noses or milder spirals. There is another example of a decorative Moro Pasión mask in Changing Faces (51).

Here is a traditional Moor mask from Tenampa, Veracruz, from my my collection, the sort of mask that must have inspired these Guerrero copies. I purchased it from Spencer Throckmorton in 1995.

The inlaid teeth are apparently made from broken pottery.

This traditional Moor mask from Veracruz has a beautiful spiral nose.

The back shows signs of an old insect infestation, which may have been treated by dipping the mask in kerosene. If that treatment was carried out, the chemical has long since evaporated, leaving no odor. Note the small metal plate below the chin, an old repair of a split in the wood.

II. Masks studded with pochote spines and or Masks featuring Caimán, Mermaid, or horned serpent body masks.

In prior posts I mentioned Nalberto Abrahán, a carver who lived and worked in Tixtla, Guerrero. Cordry had included a photo of Nalberto in his book (103) and I showed a mask that Nalberto had carved for the Manueles dance, but which was later converted to a Diablo by the addition of horns. Ruth Lechuga (in Esser 1988, page 225, 229) learned that Nalberto was the carver of the remarkable “Horned Serpent mask and step-in figure” presented in Plate 241 (194). Nalberto’s son Ruperto, who also appears in Mexican Masks with several of his masks (also 103), was identified as the carver of Plate 201 (156), a decorative “Devil mask” that has the face of a frog with two jaguars on his head. Ruperto was also the carver of an authentic mask in Cordry’s book, Plate 284 (232), “Moro Chino mask.” Lechuga was also informed that Rupeto’s son, Ernesto, was the carver of the Harvest Celebration masks (Plates 252-256, pp. 204-205), while Ruperto’s grandson, Adelfo, carved the mask in Plate 291 (236), “Angel Mask, Pastorela dance.” Adelfo told Ruth Lechuga that the angel, the harvest masks, and the horned serpent carvings were all fantasy carvings that had no traditional basis.

Already Lechuga’s research has dismantled Cordry’s careful attributions of dances and towns, leaving us to discuss the masks that remain as best we can.

Charles Thurow has another Harvest Celebration mask to compare to the five in Cordry’s book; this one, a beetle, is surely by the same hand. Two of the legs have separated from the body and must be reattached, but this remains an exciting fantasy mask.

One cannot escape the observation that this mask has been falsely aged; the paint has been rubbed off to simulate wear, and the back of the face has been stained.

The items that follow are related to the Caimán dance or to the Dance of the Fish, which overlap. As Lechuga explained (Esser 1988, ), in Chapa Guerrero there is the Fisherman’s dance, in which a dancer does wear a step-in mask (also called a “body mask”) that represents a caimán, while another dancer wears the mask of a woman and a rump mask in the shape of a mermaid’s tail. These were carved by Baldomero Mendoza. Thus we find a tradition that could easily spawn duplicates or exaggerated forms for sale to tourists. It is in this context that we consider the next group of decorative masks and accessories.

Plate 187 (137), “Caimán mask and costume, Caimán Dance.” This is a mask of a bearded man, whose nose has an odd profile and his head is studded with pochote spines. He is wearing what appear to be mechanic’s coveralls, which are painted with green and yellow lines; the coveralls are also armored with pochote spines. Such elaborate costumes are decorative, as are masks bearing pochote spines.

Plate 199 (154), “Caimán mask, Caimán Dance.” Cordry states that this green-faced mask has three noses. I would prefer to say that there are two extended caimán jaws, and above them a vestigial nose. Like the rest, this mask has many pochote spines.

Plate 247 (200), “Caimán masks, Caimán Dance.” On the left, a human faced mask has pocote spikes emerging from his hair and beard. On the right there is a similar mask, except that the hair is turquoise instead of black, and the mask has the same unusual nose as the mask on the model wearing the coveralls.

As it happens, Charles Thurow has in his collection a mask like the one with turquoise hair, although his has relief carved hair instead of additional spines.

From the side one can better see the unusual nose that is often found on these masks.

Again one finds a refreshing lack of false aging on the back.

Plate 213 (170), “Caimán mask, Fish Dance and Caiman Dance.” This is a mask with a human face and a long beard, but under the beard the jaws of a caimán are emerging.

Plate 214 (171), Mermaid masks, Fish Dance.” On the left we find a mask shaped like a mermaid. On the right there is a woman’s face, but a mermaid’s tail grows up from her face. The two masks are said to represent a daughter and her mother, according to Cordry.

Plate 263 (214), “Mermaid mask, Fish Dance.” This mask resembles that of the mermaid mother in Plate 214.

Plate 302 (244) “Caimán/Mermaid mask, Fish Dance.” This is a two-faced helmet mask. On one side there is the grinning face of a caimán, on the other a woman’s face with a mermaid’s tail rising up from her head. This is a marvelous concoction.

Plate 303 (244), “Accessories for Fish Dance and Caimán Dance” There are two step in masks, one of a mermaid with prominent exposed breasts, the other of a caimán, but with bearded human heads before and behind the opening for the wearer. Cordry states that they represent the “Old Man of the River.” There is also a necklace of carved wooden fish, which a dancer would wear as a noisemaker. These are definitely fantasy masks, but they are quite vivid and entertaining.

III. Masks attributed to José Rodríguez and his school

In this section I will discuss the masks that were attributed by Donald Cordry to an invented carver, José Rodríguez.

In her essay about the masks of Guerrero (in Esser 1988), Ruth Lechuga told of her investigation of the masks attributed to José Rodríguez. She was able to identify at least two mask makers who specialized in the carving of such masks in the 1970s and 80s, and another man, Jesús Blanco, who painted them and antiqued the finish (233). Here is a short list of masks in Cordry’s book that share the typical features of this type: Plate 15 (10), Plate 17 (14), Plate 18 (16), Plate 37 (32),Plate 38 (34), Plate 150 (106), Plate 206 (163), and Plate 248 (202). The essential feature of these masks is that there is a central face, usually a human face, that is surrounded by aspects of other creatures such as devils, frogs, bats, or whatever. I regret that I don’t have an image of a typical Rodríguez mask to show you. Lechuga included a photo of Jesús Blanco, the man who painted these masks, holding a large and elaborate example of this type of mask (Esser 1988, 242).

IV. Next I will discuss a group of masks in Donald Cordry’s collection that are dominated by images of bats. Either a bat shape is overlaid with a human face or a human face hosts a bat—Plates 23, 24, and 25 (20), Plate 67 (51), Plates 116 and 117 (83), and Plate 181 (130). Plates 30 and 31 (27), Plates 120 and 121 (85) and Plate 309 (249) show helmet masks that present either a human face or a skull on one side and a bat on the other, while Plate 258 (206) combines a butterfly with the head of a bat, to create a particularly attractive variation. Plates 276-277 (227) “Malinche and Cortés Helmet mask, Tenochtli Dance,” has lizards crawling over the faces in place of bats, but extends the two-face helmet design. Here is a striking bat mask from the collection of Charles Thurow.

This mask is an excellent example of the type of masks found in Cordry’s book that I would call decorative. However, because this mask is honestly presented, I am calling it great folk art.

The back of this mask does demonstrate some false aging effects.

Here is a list of additional decorative masks in Cordry’s book that have the theme of bats—Plates 225 and 226 (182), Plates 227, 228, and 229 (183), Plates 230 and 231 (184), and Plate 232 (185).

V. Devil Masks

In Cordry’s collection there were many masks that are said to be “Devil masks.” Cordry explains that there are local Devil Dances and there is also the concept of the devil within local dance traditions. In Mexican dances, the devil does not simply reflect European ideas about Satan, instead dance devils can play many roles—they can serve a police function, they can be clowns, and they can criticize the powerful members of their community from within this role (Cordry 1980, 245-248, Stevens 2012, 69). Devils sometimes appear in Mexican dances that are essentially morality plays, performances that depict the struggle between good and evil, such as the Pastorela and the Siete Vicios dances. As I noted in my book about the Sierra de Puebla, devils can have covert purposes within a dance, possibly functioning as representatives of precontact gods.

It would seem that the majority of the Devil masks in Mexican Masks have little if any connection to formal dance traditions, because they are invented, and attributed to a variety of invented dances. Yet they probably reflect an idea that Cordry found interesting—the precontact gods of Mexico were relabeled by the Christian missionaries as devils, creating the possibility that the faces of Indian gods might be incorporated into the appearance of Devil masks.

If one examines the decorative “Devil masks” in Cordry’s book, many of them share a few stereotyped forms. To begin with, many of the José Rodríguez masks were said to represent devils. Another subset appears to be by a different hand, such as the 12 “Devil masks” included in Plate 68 (53). These masks have human faces, but these are overlaid with some creature or creature part, such as a lizard, a scorpian, a turtle, a frog, or the antlers of a deer. Similar masks are found in Plate 51 (43), but painted in bright primary colors. Another variation, seen on four masks in Plate 40 (35), unites European devil’s faces with applied elements, “Pre-Hispanic water symbols of snakes, frogs, and fish.” Four more of this type appear in Plate 133 (93); 133d; the last of these may be an authentic or made for sale mask by Victoriano Salgado, of Uruapan, Michocan. A striking variation in Plate 41 (35), “Devil mask, dance unknown …Michoacán,” has a devil’s face, with two sets of horns formed from “segmented wormlike creatures,” while one menacing snake emerges from the devil’s mouth and another crawls through the space between the forehead horns and hovers over the face. This is definitely one of the most exciting masks in the book, for me. But of course it is not from Michoacán and no mask of this specific design is known to be associated with any Mexican dance.

There are other masks in this book that are not labeled as “Devil masks,” but they are said to have been used in a “Devil Dance.” Such is the case for the delightful pair in Plate 9 (7), “Chameleon masks, Devil Dance.” Of these, Cordry states— “I know of no use for these masks save an Animal Dance that today would be termed a Devil Dance” (7). Flawed explanations lead to flawed theories.

Ruth Lechuga’s research revealed that the “Devil mask” in Plate 189 (140), a human face carrying two large lizards, was carved by Baldomero Mendoza of Chapa, Guerrero, the arstist who had carved the tradional masks and dance accessories for the Fisherman’s Dance in Chapa . When Lechuga showed him the photo of this mask in Mexican Masks, he was surprised to see the effects of false aging techniques. The mask had been commissioned by a dealer in Iguala, Guerrero, and Baldomero had delivered the mask in perfect condition.

Baldomero Mendoza was also the carver of two of the most extraordinary objects in Cordry’s book, seen in Plate 50 (42), “Rhythm-makers masks, Owl Dance.” These have the appearance of totem poles, or of columns of masks, each column capped by a carved owl. One is about 48″ tall and the other is a little taller. Based on Cordry’s perspective, I should have presented these carvings in a later section about animal masks and the Lord of the Animals, but these categories seem less and less meaningful as we learn of the fictitious nature of the masks’ labels.

In yet another variation of the Devil masks, Plate 193 (145), “Devil masks, various dances,” the masks have the faces of birds. A large crow’s head has a human skull on its forehead, while a smaller mask has the curled beak of a vulture; that mask has a small human face on its forehead. This represents a “spirit helper,” says Cordry. He was fascinated by the idea that masks might bear images of spirit or animal helpers, to lend power to the dancer. There are genuine masks that bear symbols for this purpose, such as Yaqui Pascola masks that have a cross painted on the forehead. However, the so called spirit helper masks in Cordry’s book are all invented.

By now we have discovered that Cordry used the term—Devil mask—to refer to a wide variety of designs and purposes. In fact there are more to come. On Plate 200 (155), “Devil masks, various dances,” we find masks with small human figures in their open jaws. These are children’s bodies, notes Cordry, and they may reflect precontact traditions of human sacrifice. The decorative masks provided Cordry with distorted and inaccurate data, upon which he engaged in loose speculation and drew conclusions that are potentially offensive to Indian peoples of the Americas.

Plate 259 (207), “Malinche mask, Pastorela Dance,” deserves special attention on two counts—first, because it has devil’s horns, and is thus a diabla (female devil), and second, because this wooden mask of unusual design was apparently the model for a near duplicate, formed from copper—Plate 278 (228), “Malinche mask, probably Malinche Dance.” Instead of wooden rams horns it has deer horns, and is once again a diabla. These two masks are flagrantly decorative, so extreme that I find them fascinating.

There are a few additional Devil masks that fall into one or another of the styles already described—Plates 248 and 250 (202), Plate 251 (203), Plate 257 (206), Plate 269 (218), Plate 292 (236), Plate 293 (237), and Plate 296 (240).

I do not have an image of a decorative Diablo mask to show you. However, I do have a mask from the collection of Charles Thurow that falls somewhere between the José Rodríguez masks and the Devil masks.

This mask has a human face peering from the body of a winged caimán. The caimán’s tail simultaneously functions as a colorful headdress worn by the human. This reminds me that one of the common features of many of Cordry’s masks, and perhaps a feature that Cordry evoked in the masks that were consciously created for him, was the theme of shamanic transformation, the shaman’s quest to enter the realm of animals and spirits in a trance state, in search of power. This mask seems to portray a shaman who has been transformed into a flying caimán.

VI. Masks of Animals and Lord of the Animals masks

Many of these simply present the head, or the head and torso, of some animal. Plates 26 and 27 (21), for example, are based on the head of a deer, Plate 80 (61) has the face of a jaguar, Plates 82, 83, and 84 (62) feature the head or the shell of an armadillo, Plate 176 (127) has a jaguar’s face, and Plate 180 (130) has the face of an owl. Plate 195 (147) has a human face that is partially covered with the hide from an armadillo. Plate 202 (158), “Tigre masks and costumes with small tigres,” resembles the “Caimán mask and costume” that we had discussed earlier, in that the dancers wear coveralls that are ornamented with small carved jaguar heads, mirroring their jaguar masks. Like the suit of the Caimán, these jaguar suits with attached maskettes are invented, and decorative. Tigre dancers in Chiapas do wear traditional jaguar suits that have painted stripes or spots, but those suits lack the applied maskettes. Cordry illustrated a detail from one of these authentic suits in Plate 223 (180) and I illustrated such a suit in my last post. Plate 240 (193, shows a pair of amusing masks—”Mask for Coyote Dance (a); Dog mask for Tlacololero Dance (b).” In this pair we find, once again, variations that follow a formula. The first mask has the head of a wolf or coyote, with identical miniature projecting heads on the forehead and on both cheeks. The second has the head of a dog or a cat, and small cat’s heads project from the areas where one would expect ears. One could imagine a carver making dozens of permutations of this design—fish with fish ears, lizards with lizard ears, etc. In fact, Plate 244 (199), “Dog mask,” has a carefully carved dog’s head that has caimán ears. On reflection, many of the decorative masks in Cordry’s book seem to have resulted from such formulaic designs.

Donald Cordry believed that there was a surviving dance that was based on traditional shamanism—the Lord of the Animals Dance—and that there were also masks to be found for that dance. I can understand Cordry’s theory, as I have been exploring similar ideas with regard to the Yoeme (Yaqui) Indians of Sonora, Mexico. Plate 219 (175), “Mask probably for Lord of the Animals Dance,” introduces this theory and this is another mask that Cordry attributes to the hand of José Rodríquez; a mask of what seems to be be an owl-man has the head of a snake or lizard for its nose, while a pig’s head emerges from the owl-man’s chin. This complex face wears a circular crown, upon which and from which a band of monkeys hang or play. The mask is initially confusing , then rather interesting, but definitely strange and unfamiliar. Plate 221 (177), “Helmet mask, said to have been for Coyote Dance,” is less strange and more immediately attractive—there is the face of an old man with a long wizard’s nose, but masks of a coyote and an owl appear in place of his ears. Cordry believed that this mask was also associated with the Lord of the Animals Dance. This brings us to Plate 222 (179), “Animal masks and four Lord of the Animals masks, Animal Dance.” Cordy attributed this set of masks to José Rodríguez as well. He comments that “In the top row we see four anthropomorphic Pastores (Shepherds) who represent the Lord of the Animals.” There are eight animal masks in the rows below the “Pastores.” Cordry went on to comment that “these animals suddenly came on the market in 1976, then disappeared entirely, indicating that this Animal Dance is no longer in fashion.” I can only say, in all humility, that Cordry was not so different from the rest of us in his willingness to adapt his thinking, in order to explain or justify something that interested him. It is my opinon that all twelve of these masks are decorative, and that their brief availability reflected the time of their invention and manufacture. As I have said in earlier posts, I particularly doubt these masks because they appear to have been deliberately carved to a crude or primitive standard, in contrast to the vast universe of well carved traditional Mexican dance masks.

VII. Masks with double or triple faces

Plate 47 (40), “Death masks, various dances,” includes two masks with double skulls. In her research, Ruth Lechuga learned that those masks were carved by Rodolfo Blanco, the brother of Jesús Blanco. She also noted the photo of Miguel Cruz López (Cordry 1980, 135, Plate 186), “carving a Twins mask for the Máscaritas Dance.” The Máscaritas Dance is a variant of the Danza de los Tejorones, found in Mixtec villages such as San Juan Colorado, Oaxaca. When I observed this dance there in recent years the dancers wore masks with single faces. Miguel informed Ruth Lechuga that these masks were not used in dances. Nevertheless, in Plate 209 (166), “Twins masks, Dance of the Twins,” Cordry shows us four of these masks by Miguel Cruz López, and repeats his belief that these masks were danced in San Juan Colorado. In Plates 207 (164) and 208 (166), Cordy shows seventeen “Double- and triple-face masks, Quilinique Dance,” which he describes as ancient and little known; these masks are clearly by another hand.

In a “Cordry moment,” in 2001 I purchased a double faced mask that was said to have been danced in the Mixtec area of Oaxaca, an area that is of special interest to me. I have since doubted this history, and I now believe that this may well be another decorative mask, probably from Guerrero. It does demonstrate a unique design, as it has three eyes and two noses. Therefore I acknowledge my place in the reluctant ranks of those who have probably been deceived by the decorative masks, and I will display this mask without further comment.

In my experience, virtually all multifaced masks from Mexico are invented and decorative. However I have discovered one exception to this rule, the three faced Santiaguero masks from San Antonio Rayón, Puebla that were carved by Narciso Iturbide Charo in about 1970. I know that these are authentic because I have found a dance photo from the early 1980s and I have interviewed a former participant in the dance. I wrote about this carver and his masks in my book, Mexican Masks and Puppets (pages 123-129). Here I will include some photos of one of these authentic three faced masks.

This mask is from the only tradition of authentic Mexican three faced masks known to me, used in the Santiagueros dance in San Antonio Rayón, Puebla. The white patch on the forehead is a plaster repair. These are the faces of Pontius Pilate, King Herod, and Caiaphas, the High Priest of the Jewish Temple at the time of the Crucifixion of Christ. Obviously this mask was meant to be the personification of evil!

The face on the right side of the mask.

The face on the left side of the mask.

This is the back of the three faced mask from San Antonio Rayón, Puebla.

VIII.Decorative Tlacololeros masks

Plate 216 (173) contains dramatically oversized masks in the style of traditional masks used in Guerrero for the Tlacololeros Dance. These masks also vary from the norm by their painted faces. “These intense faces are richly carved and painted in sections, most probably to denote the look of the fields and crops during various stages of the slash-and-burn agricultural cycle,” explains Cordry. These “color block” Tlacololero masks are all invented and elaborated versions of their traditional counterparts. Here is a mask in this style from the collection of Charles Thurow. I do find it attractive in these colors. I showed a conventional Tlacololero mask in my post of August 4, 2014.

The areas of rubbed paint on this mask have the typical appearance of false aging techniques. For example, the side of the mouth shows paint loss, as if from abrasion, but this is an area that is sheltered by the mustache, which demonstrates no damage. That is, paint loss in hollow spots should always arouse our suspicion.

At first glance, the back of this mask seems to demonstrate the differential staining of a danced mask, but then one realizes that the staining extends to the top of the back, an area that would be far above the wearers face and hair, because this mask is 17 inches tall. This is a mask that has been falsely aged in a skillful manner.

IX. Pre-Columbian designs

In Mexican Masks there are five decorative masks that were inspired by helmets worn by Indian soldiers in the period before the arrival of Europeans. Such helmets, which framed the warrior’s face within imitation heads of eagles or jaguars, were meant to enhance the soldiers’ fierce appearance. So one reads of “Eagle Knights.” In their book, Mask Arts of Mexico, Ruth Lechuga and Chlöe Sayer note that such designs have inspired traditional dance masks in the communities of Huayacocotla and Silacatipan, in the Mexican state of Veracruz, and they show three examples (1994, 82-83). The decorative masks of this form in Cordry’s book are said to be examples from the state of Guerrero; four of the five are very large, while the smaller one has an almost cartoonish appearance. These are found in Plates 131 (90), 190 (143), 191 (143), and 215 (172). There are some additional examples of this type of decorative mask in Changing Faces (48).

Here is a photo of a traditional Jaguar mask from Veracruz that has a nearly large enough open mouth to reveal a warrior’s face and the dancer has the option of looking through the vision slits under the eyes or through the mouth (from my collection). The masks in question reveal a carved face within the animal’s open mouth, and the wearer has similar vision slits.

(Not a decorative mask, but a prompt to help you to imagine a decorative variation.)

Next I will show an authentic example of an Eagle Knight mask from Carpinteros, Veracruz, a village near Huayacocotla. This mask had severe infestation in the past with boring insects. Despite its condition, this is a very interesting mask. The back demonstrates significant wear.

X.Masks of Human faces with Strange Projections

There are four decorative masks in Cordry’s book that have unusual stalk-like projections. Two appear in Plates 56 and 57 (46), and two more in Plate 92 (69).

XI. Masks made of copper (or silver)

In this book there are several decorative masks that were hand tooled from copper sheets, and others made from sterling silver. Donald Cordry owned many more of these copper masks, and I have seen entire walls in important museums that were covered with such masks from his collection. Ruth Lechuga’s research led her to identify the craftsmen who made these masks (Esser 1988, 241, 243), and they acknowledged that these were newly invented and non-traditional. Here is a list of the metal masks—Plate 20 (18), Plate 21 (19), Plate 47, lower left (40), Plate 154 (108), Plates 157 and 158 (113), and Plate 278 (228).

Here are two copper masks in the collection of Charles Thurow.

This is a very large mask—24 inches tall and 15 inches wide.

This mask is 15 inches in diameter.

XII. Decorative masks of leather

In Changing Faces (51), a leather mask of a bearded man is identified as a decorative mask, although it was made on a traditional mold. In Plate 16 of Cordry’s book (116), the mask on the lower right is m/l identical to one in Changing Faces. Masks 161 b. and c., in the top row, seem to be by the same hand. Plates 238 and 239 (191), Maravilla (Dog) mask, Tecuani Dance,” show another decorative mask, this one of a dog. Plate 22 (20), “Helmet mask, Vaquero Dance (?),” is another of a several very strange masks in Cordry’s book. There is a leather face, a wooden nose, wooden horns, and what looks like a traffic light (also made of wood) that rises behind the wearer’s head. When I visited the Rafael Coronel museum, in Zacatecas, I was shocked to see a duplicate of this mask there, or perhaps it was this very mask. Cordry notes that this is a large mask that rests on the dancer’s shoulders. Such a remarkable invented mask is truly worthy of our interest.

Here is a leather mask from the collection of Charles Thurow that resembles the one in Plate 16 and the other in Changing Faces.

I believe that the back of this mask has been stained, in order to give the false impression of wear.

XIII. Masks of bone

In Plate 156 (112), “Mojiganga Procession Masks,” Cordry shows mammal pelvis bones that were allegedly worn as masks. Jaled Muyaes regarded these as decorative. But Jaled did not identify the mask in Plate 112 (81),”Mojiganga Procession mask,” shown in a dance photo”,as a decorative. I don’t really know whether these are traditional or decorative.

XIV. Other

Plate 110 (80), “Maromero (Tightrope Dancer) masks and Meromero somersault figure, Lenten Fiesta and Fair.” Cordry believed that these items had been used in street theatrical performances, fifty years earlier. To my eye, the two masks seem little different from others that are decorative in Cordry’s book. Jaled Muyaes also thought that these were decorative. Yet one must admire the imaginative efforts of those who prepared such things for Cordry.

Plate 294 (239), “Vaquaro Mask, Vaquaro Dance.” Ruth Lechuga was told by Baldomero Mendoza that he made this mask for his own use, but then sold it to a folk art dealer, who resold it with an invented provenance. Therefore this mask was originally within the Mexican masking tradition, but it became a decorative mask purely because of false and invented attribution.

I hope that you have enjoyed this lengthy review, over four posts of mine and a fifth by Charles Thurow, of decorative masks and their place in Donald Cordry’s book, Mexican Masks. Next week I will move on to an entirely new topic, telling about an old set of authentic masks that were used for the “Dance of the Dead” in the Mixteca Alta, during the early decades of the 20th century.

5 comments on “Mexican Masks—An Important Book By Donald Cordry, Part 3”