Today we will view photos from a recent visitor, who provides us with examples of masks from a particular Morería, that of Cruz Juárez in San Miguel, Totonicapán, Guatemala. These masks are branded with two consecutive capital letters, C and J.

An enlightening book— Máscaras y Morerías de Guatemala/Masks and Morerías of Guatemala— was published by the Museo Popol Vuh of the Universidad Francisco Marroquín in 1993. The author was Luis Luján Muñoz. For those of us who were collecting Guatemalan dance masks at that time, this was our bible. One learned there that the Morerías were essentially cultural centers which specialized in the creation and maintenance of dance masks and costumes that were necessary for the performance of traditional Guatemalan dance dramas. In recent centuries these were family operated business establishments, although in earlier times they may have been indigenous tribal institutions. The proprietors of the Morerías were responsible for the creation of appropriate dance costume elements, and as I related in last week’s post, they maintained Spanish Baroque carving traditions that had been introduced by European missionaries, centuries earlier, for the carving of Saints in Roman Catholic churches.

In the Máscaras y Morerías book Luján Muñoz included a list of the brands (proprietary marks) that had identified the masks produced by the various Morerías, including the “C J” mark used by the Morerías of Cruz Juárez, in San Miguel Totonicapán and later in San Cristóbal (pp. 67-69) during the 20th century.

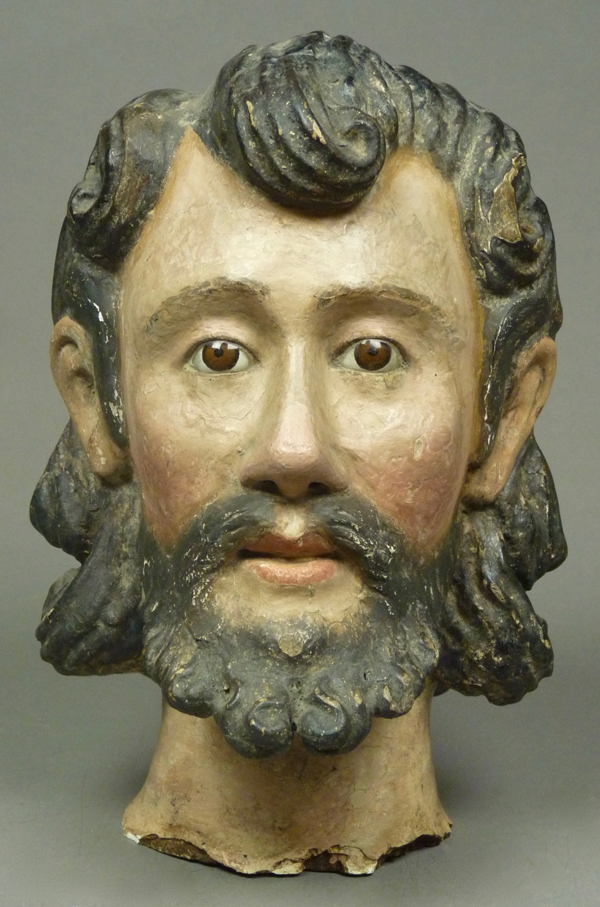

In their vivid and detailed compendium—Masks of Guatemalan Traditional Dances (two volumes, 2008)— Joel E. Brown and Giorgio Rossilli included a discussion of these marks (Volume 2, pp. 629-636). and they presented photos of the C J mark (p. 630). I have never owned a mask with this mark, but today we will see six of them from another collection. Although all six have European features, so that we might be quick to call them Spaniards from the Conquest Dance, they could have been worn during La Danza de los Moros y Cristianos, La Conquista, or Los Vaqueros/ Toritos. Mask details sometimes suggest whether a mask can be ascribed to one dance or another.

Jim Peiper, in his Guatemala’s Masks and Drama (2006, page 58) included a photo of a mask with the C J brand, but he attributed it to another morería. This book does contain many wonderful mask photos and much information of interest.

The first of the masks in today’s group has a very dark complexion. We find a very similar mask in Brown and Rossilli (Volume 1, page 60), labeled as a “Moro.”. It has the same colored eyes and the C J mark on the back.

Note the dark complexion and dark red cheeks.

Continue Reading →