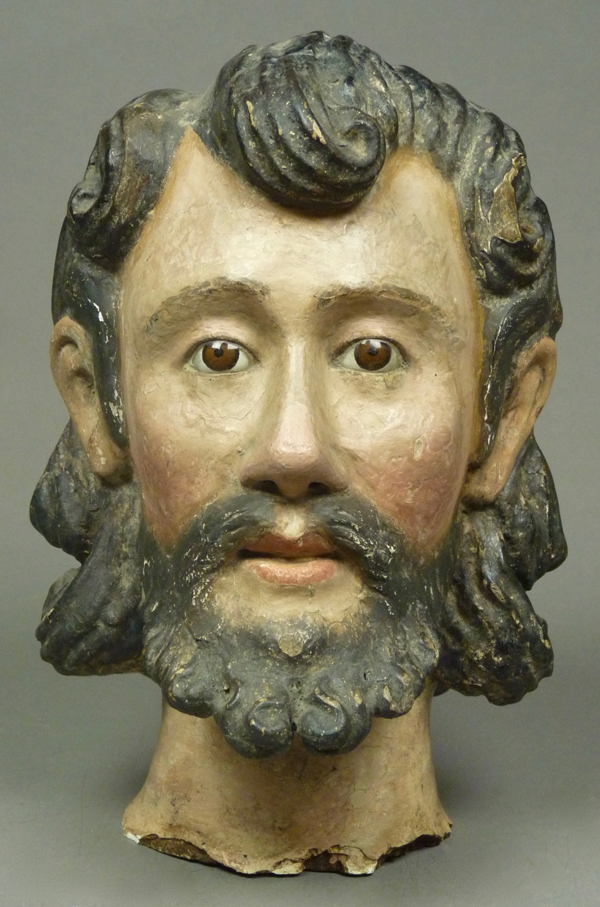

In early November, 2019, I became enamored of what appeared to be a rather old wooden head from a broken Santo figure. The seller stated that it was from a convent in Peru that was being restored during the first decade of the 21st century, and so old cast-offs such as alter cloths and this head were being sold to raise money for the restoration. The head had been separated from the body of the Santo in the 1820s, during an earthquake, the body of the saint having been destroyed. There are at least two Peruvian convents that match up with these dates (earthquakes in the early 1800s and restoration in the early 21st Century)—one in Arequipa and the other in Lima. The head was said to be from a statue of Saint John the Baptist, but the seller thought it might be the head of Christ, and my initial vote was for San José (Saint Joseph). My reasoning was that John the Baptist is frequently presented wearing an animal hide, so that the elaborately coiffed hair found on the Peruvian head seemed to point elsewhere. However we are discussing Baroque images, so perhaps even John the Baptist required such a nice haircut. Christ is seldom represented in paintings or Santos as serene; usually he is depicted in agony. On the other hand, paintings and Santo figures of Saint Joseph frequently show him holding with one hand the flower staff that marks him as the father figure of Jesus, while the other arm cradles the Infant Christ. In these images Joseph usually has the serene smile that we will see on my Peruvian head. Here is an initial look at that head.

Here is a Santo from my collection that presents San José with a staff and holding the Christ child on his hand. This old and obviously beloved carving was collected in the 1990s from a Chatino village on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca. Why would someone sell such a treasure, one might ask. Large numbers of Indians had converted to the Protestant faith, and they were instructed by their pastors to divest themselves of religious images, so they sold off their Santos. The Protestant concern about such images is that they tend to function as intermediaries between the worshiper and God. Thus we find a bare cross in the sanctuary of Protestant churches and Christ on the cross in Roman Catholic churches.

This San José has lost one if his feet.

Isn’t this a sweet carving of the Infant Jesus.

The thread is, of course, meant to prevent Christ from falling off the Saint’s hand.

Jesus was said to be precocious.

This figure is 14 inches tall.

Next I will include two masks from Michoacán that depict San José . You may have seen these in my posts in September, 2017. The first even has hand made glass eyes in the manner of the Santeros tradition.

https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=10583#more-10583

In Michoacán, the dancer wearing this mask is also called Terépiti, or Grandfather.

This mask is 10 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3¼ inches deep.

Here is a second example of one of these Tarépiti, Grandfather, or San José masks.

The wig is made from goat tails. This mask lacks glass eyes.

This mask is 10 inches tall, 5¼ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

Now I will look closely at this Peruvian head in multiple views. I will begin by repeating the frontal view that you saw earlier.

This is such a beautiful head that I think mere words are insufficient and unnecessary. Feast your eyes.

This is the serene smile that I am talking about.

The hole on the back of the head may have held the foot of a wire halo.

This head is 9 inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 6 inches in depth.

The head was connected to the body by a dowel peg.

I bought this next mask from Spencer Throckmorton in 1996. I’ll call it a mask of a Spanish Soldier, as it appears to be a junior version of an Alvarado mask from the Guatemalan Conquest dance. I include it here as an example of what happens when you ask a Santero (a carver of Saints such as our featured head) to make a mask; he makes one that looks like a Saint. It even has glass eyes. Many of the masks in Guatemalan dances appear to have been carved according to the Baroque traditions exemplified by Spanish wooden saints and their derivatives in the Americas. I don’t have a Peruvian example to illustrate this.

For example, look at the finely carved ears on this mask.

This mask is exquisitely carved. It measures 7 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches in depth.

The initials ET are carved on the back, the trademark of a well-known Morería (mask rental establishment) in San Cristobal, Totonicapan, Guatemala.

In next week’s post- a reader has sent photos of old masks from Guatemala for us to examine.

Bryan Stevens