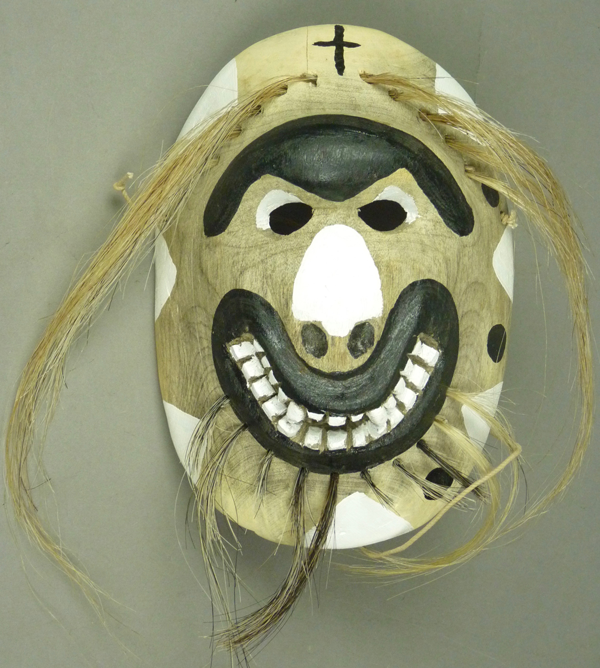

Today we will examine three Sinaloa Judio masks that demonstrate the evolution of these masks to ones that have larger wooden faces than the traditional masks and with more graphic and dramatic features. Large mask-like faces have replaced the much smaller face plates that were an earlier innovation, sixty years ago. When my friend Tom Kolaz first sent me photos of this mask in 2007, I felt very skeptical about the whole concept, and I suspected that Sinaloa Mayo performers were importing masks from other states in Mexico to enhance their Judio masks. At that time there were not yet YouTube™ videos available of these dances. But then Tom sent me a photo of a Mayo man who claimed to be the carver, and he was holding this mask before it had been combined with a fur cowl to form a Judio mask. That carver’s name was Cesar Velasquez. He sold the mask to Tom after it had been danced, and I purchased it in September 2008.

This mask appears to represent an American Plains Indian, perhaps an Apache. In the recently available YouTube™ videos included in my last two posts, you may have noticed that such Apache type Judio masks have become popular during Semana Santa performances, along with many other formerly unusual types such as Diablos.