In his Masters Thesis of 1967 on Rio Mayo masks and carvers, James Griffith wrote about Plácido and Marcelo Alamea (pp. 105-107). Marcelo was Plácido’s son and both are deceased. In the Spring of 1965, when Griffith was working in the Rio Mayo region, Plácido was about 60 years old, and living in Jitombrumui, Sonora. He had danced as a Pascola, foot pain led him to retire, but he continued to play the violin at fiestas. “He also makes violins, harps, and masks, and has some reputation as a curandero,” wrote Griffith. Marcelo , who was living in Loma del Refugio, Sonora, was also a mask carver and a festival violinist. Griffith felt that father and son carved similar masks, as if there might be an Alamea family style. He described their masks as having “complex borders” and observed that ” six of the masks have horizontally flat faces with vertically convex cheeks.” When present those cheeks do provide one marker for masks carved by the Alameas, although some of their masks lack this feature.

Mexican Masks, by Donald Cordry, was published in 1980. In that book we find a photo of “Don Plácido” that was taken by Cordry in Antanguisa, Sonora in 1938 (plate 140, page 101); Placído was carving a mask and a completed mask was nearby. According to Leonardo Valdez, who had assembled a Museo (museum) collection of Mayo dance material in Etchojoa, Sonora, this Don Plácido was Plácido Alamea. Leonardo had one of Plácido’s harps on display in the Museo. Unfortunately I have been unable to locate Antanguisa. Griffith shows Jitombrumui on a map that indicates it lay 10 Km. to the west of Navojoa (and 10 km. west of Loma del Refugio, Marcelo’s village).

I visited Jim Griffith at his home near Tucson in 1990, and he kindly allowed me to photograph the masks he had collected during his research among the Mayo Indians of Sonora. At the time I wanted these photos as visual records of carver’s styles (a reference library), and I never sought his permission to publish those images. Since then Jim has donated those masks to the Arizona State Museum in Tucson, Arizona. At about the same time I obtained the book written by James Griffith and Felipe S. Molina, Old Men of the Fiesta:An Introduction to the Pascola Arts (1980), and I began visiting the Arizona State Museum’s Yaqui and Mayo collections. Through these experiences I discovered the masks of Plácido and Marcelo Alamea. Today I will focus on Plácido.

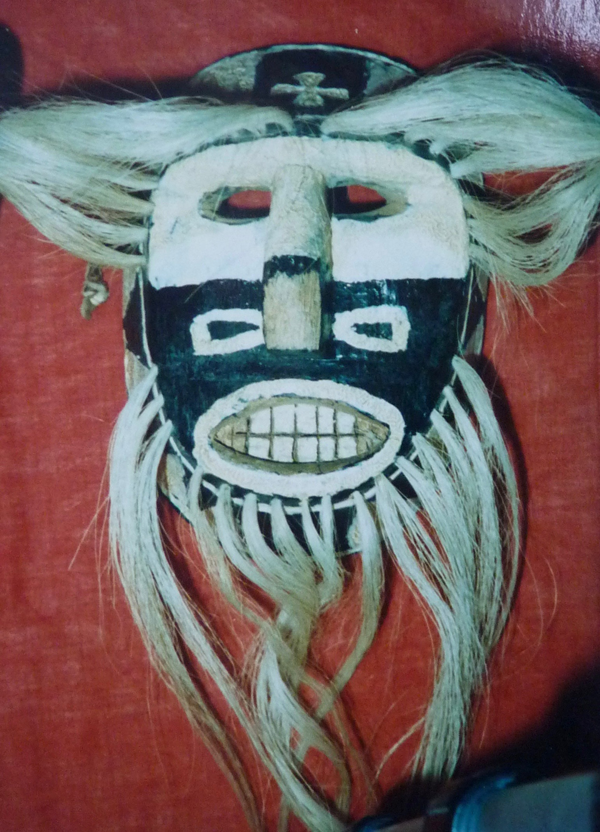

Here is one of the masks carved by Plácido Alamea that was collected by James Griffith during his research in 1965. What a beauty!

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/318629742362788611/

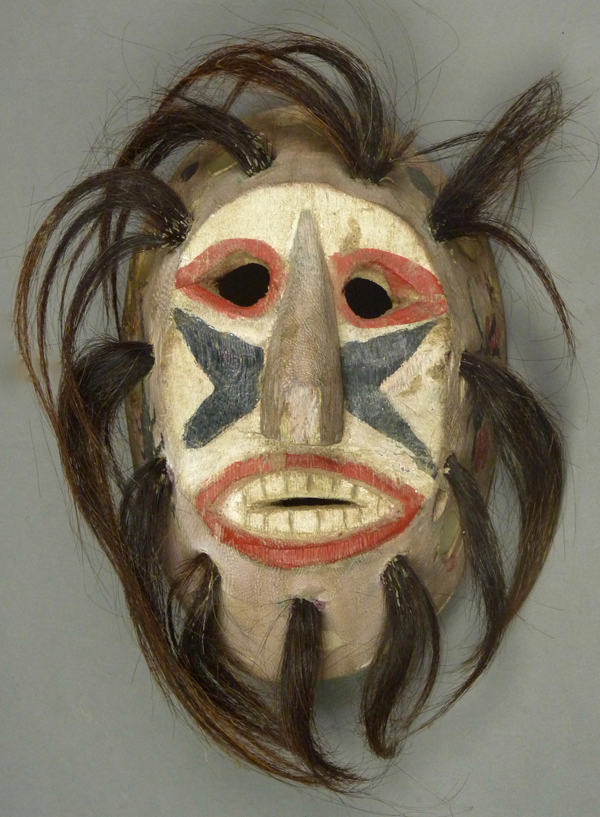

From the time that I first discovered Plácido’s classic mask style, I wanted one or more for my collection. Ultimately one doesn’t get to collect what they want, but what they encounter. I wasn’t able to buy a mask by Plácido until 10 years later, when Tom Kolaz offered to sell me one. As you will later see, this is a very unusual and interesting mask. Then, in around 2005 I obtained a more classic example, which I will show you first. I bought this mask from the John C. Hill Indian Arts Gallery in Scottsdale Arizona, with no provenance. While this mask exemplifies Plácido’s style, I am uncertain whether it was carved by Plácido or Marcelo.

On first glance, you may have noticed that this mask exhibits many generic Rio Mayo Pascola design elements, such as the chevron shaped wedges that flank the nose, a forehead cross composed of four triangles with their points together, a mouth like those on masks by Pancho Parra and Bonifacio Balmea, and hair bundles that frame the face in a circle. These are all typically found on Alamea masks. An unusual detail is the chin cross, which matches the one on the forehead, and appears to be original to the mask. The rims of the eyes were carved in relief, another common feature of masks by the Alameas.

Continue Reading →