In April 2006 I had the great pleasure of traveling with a group from the Arizona State Museum, in Tucson, to the Rio Mayo villages in Sonora to observe Easter celebrations by the Mayo Indians there. We were led by Diane Dittemore, a curator at the Arizona State Museum, with the assistance of Emiliano Gallega Murrieta, an ASM Intern who had grown up in Sonora. We visited Leonardo Valdez, who had established a Museo in Etchohoa to display his collection of Mayo Fiesta regalia. By coincidence, we ran into Bill and Heidi LeVasseur there; they later established a mask museum in San Miguel D’Allende, and Bill’s book followed to catalogue their museum collection—Another Face of Mexico (Art Guild Press, Santa Fe New Mexico, 2014).

The group encountered a number of Mayo Pascola dancers, and we saw some attractive masks being danced, but it seemed that those were not available for sale at that time, and perhaps they were already promised to Leonardo Valdez. Then again, it is also my impression that danced masks are frequently not sold in the exciting time surrounding a fiesta, particularly if the dancer is using his favorite mask. Later, when the dancer wishes to raise cash, he may sell a mask that is no longer wanted.

We also visited with several mascareros (mask carvers) and they did sometimes have new and undanced masks to sell. This leads me to the subject of “made-for-sale masks.” Popular carvers are often asked by Pascola dancers to make masks to order, with particular desired features and sized to suit that dancer. However, in the absence of such orders the carver may elect to produce masks that he hopes to sell to some future customer. These made-for-sale masks may reflect local traditional design preferences or not. Ultimately they will prove to be either suitable or unsuitable for use by the average Pascola dancer, depending on the mask’s details and the dancer’s preferences. The suitable masks are meant to interest dancers as well as tourists or collectors, while the unsuitable ones are obviously produced for the latter groups and not for traditional use. Thus the term made-for sale is not inherently indicative of whether a mask is faithful to local traditions or not. In today’s post we will look at a pair of made-for-sale masks.

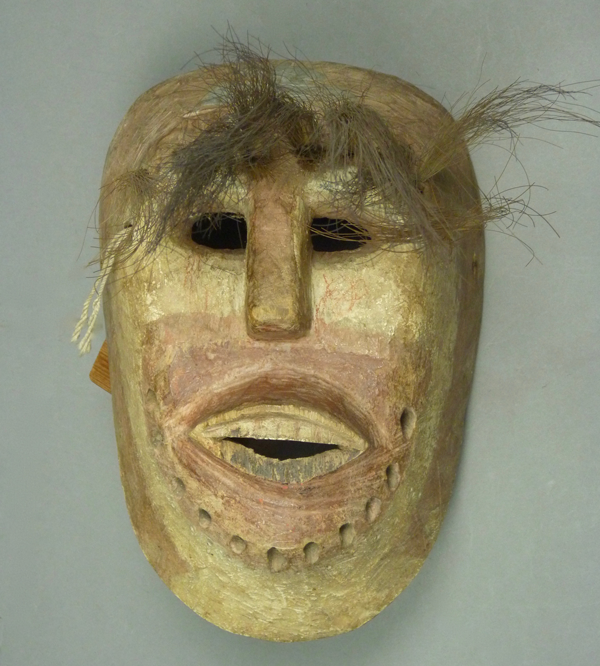

I bought this first mask from Arnulfo Yocupicio when we visited him at his workshop, in Masiaca, Sonora. I don’t know whether Arnulfo is related to Manuel Yocupicio. He carves traditional human faced Pascola masks that are painted black, along with others of dogs or wolves. Here is one of those wolf masks. Although such canine masks are popular among Yaqui Pascola dancers, one only occasionally sees danced Mayo examples.

This mask has very long (and carefully applied) hair, a trait that Rio Mayo carvers had recently copied from the Rio Fuerte Mayo style in Sinaloa.