This is the fourth and concluding post in a series that explores and attempts to clarify the boundary between authentic Mexican dance masks and other invented (or “decorative”) masks that pretend to be authentic. This boundary had become dramatically blurred after the publication of Donald Cordry’s book, Mexican Masks, in 1980.

It would be easy to wonder about the value of Donald Cordy’s book—Mexican Masks—after learning that two thirds of the masks can be described as falsely presented (or “decorative”). In the last two posts I called your attention to the fact that the masks that make up the other third are not simply good, but frequently great. Today’s post will identify and examine the decorative masks in this book. For those of you who are joining this blog for the first time, there is a very brief explanation of “decorative” masks in the FAQ section (Question 7), a very detailed discussion in my post of August 4, 2014, and further comments by my friend Charles Thurow in the post of August 20, 2014.

As I noted in earlier posts, any attempt to specify exactly which of these masks is decorative is likely to contain an occasional error. The problem is this—there are so many variations in mask designs and related dances in the villages and towns of Mexico, and so many independent carvers, that no single person can possibly know everything that there is to know about these variations. In recent posts I pointed out instances of disagreement between myself and a very knowledgeable collector, Jaled Muyaes. I noted other instances when the two of us agreed that we didn’t know the status of a particular mask or group of masks.

In spite of this inherent ambiguity, various experts have made some effort to define those masks that are decorative. I introduced their work in my post of August 4, 2014. Despite their writings, which are admittedly in relatively rare, inaccessible, and out of print books, typical decorative masks like those in Cordry’s book continue to show up for sale, for instance on EBay™, with descriptions that suggest that these are authentic and traditional. That is, such masks continue to be falsely presented, despite Ruth Lechuga’s careful explanation in 1988 (in Behind the Mask in Mexico, edited by Janet Esser). This is why I have chosen to tackle this subject on these pages. I believe that the continuing false presentation of these masks has actively discouraged the appreciation of a huge body of remarkable Mexican masks that are traditional, authentic, and meaningful within their respective cultural contexts. Furthermore, this inaccurate labeling tends to discredit the invented masks as well, by inviting us to evaluate them according to specious attributes, rather than on their own merits. Nor do the prospective sellers of these masks benefit, when their erroneous and inflated ideas about the value of these masks frequently prevent the masks from finding buyers, even though there are collectors who appreciate these non-traditional masks as folk art.

In my last post (August 18, 2014) I was pleased to include many photos to illustrate the sort of authentic masks that are found in Mexican Masks. I wish that I could do as much for the decorative masks, but I have actively avoided their collection, so that I have very few of them. Fortunately my friend Charles Thurow, along with his late partner, Dale Hillerman, had chosen to consciously collect masks that we might have called decorative. Despite knowing the true origin of these masks, they nevertheless thought of them as great folk art. Charles has permitted me to photograph masks from their collection, I included some of the traditional masks in my last post, and today I will gratefully present the non-traditional masks, but without false labels.

I want to reiterate that although I will refer to these masks as “decoratives,” we could as readily refer to them as examples of folk art, provided that they were accurately labeled. The problem is that they are falsely labeled in Cordry’s book, whereas the examples that I will include from the Hillerman/Thurow collection will be free of such fiction and fantasy. Therefore in this week’s post I will call each of the mislabeled examples found in Mexican Masks decorative.

It has been an interesting experience for me to revisit the decorative masks in Cordry’s book and to see them through the eyes of Charles Thurow. As I noted in my August 4 post, and as Charles further explained in a special post of August 20, 2014, he prefers to focus on these masks as remarkable artistic creations by individual artists. He is not insensitive to the problematic nature of their labeling and marketing, although he also perceives this aspect as a reflection of the long history of miscommunication and sparring for advantage between indigenous peoples and those of European descent. Equally interesting has been my recognition of patterns within this heterogeneous collection—to essentially observe the unfolding or invention of these masks in a sequence that reflected the interaction between Cordry’s curiousity and the desire of his opportunistic dealers to accommodate him. I can’t say that I know what came first and then what else came next, but rather I can see the breadth of variations that were provided in response to Cordy’s inquiries, and I can see how interesting that process became for Cordry, and potentially for some of us.

In my last post, I discussed the traditional masks in their order of appearance in Cordry’s book, acknowledging the unique nature of each mask. I will approach the decorative masks with a different strategy, grouping them into arbitrary clusters. I am not particularly pleased with this clustering task, as it must sometimes hinge on false ideas or labels instead of the actual mask forms; for the sake of discussion I have to start somewhere.

I. Masks with elaborate curling beards, Moors and Christians, and Archareo Masks

Some of these are the masks that Charles Thurow and Robert Anderson viewed as extensions of the baroque Christian art that was introduced into Mexico in the sixteenth century and others are bearded helmet masks. Here is a list of the masks of this type in Cordry’s book, with his labels and my remarks—

Plate 10 (page 7), “Vaquero, Vaquero Dance, Guerrero.” This mask has an articulated jaw that is connected to the central section of the beard, creating a large swinging panel. Of all the masks in the book, this is one of the strangest.

Plate 16 (13), “Probably for Dance of the Marquez.” This is a good example of the most impressive and beautiful of the Baroque style decorative masks, carefully carved from cedar, and with the misleading appearance of great age and wear. At least five near duplicates appeared in the Celebration of Masks book. I am sorry that I don’t have a good photograph of this type to include here.

Plate 32 (27), “Barbones (Bearded Ones) masks, Dance of the Marquez and others.” These masks have pink faces and elaborate beards. Although dramatic, they are not quite as impressive in appearance as the one in Plate 16, and they are made of zompatle wood, which is lighter, more fragile, and more easily carved than cedar.

Plate 188 (138), “Dwarf Masks, Dance of the Dwarves.” These resemble those in Plate 32, although they have been attributed to another dance.

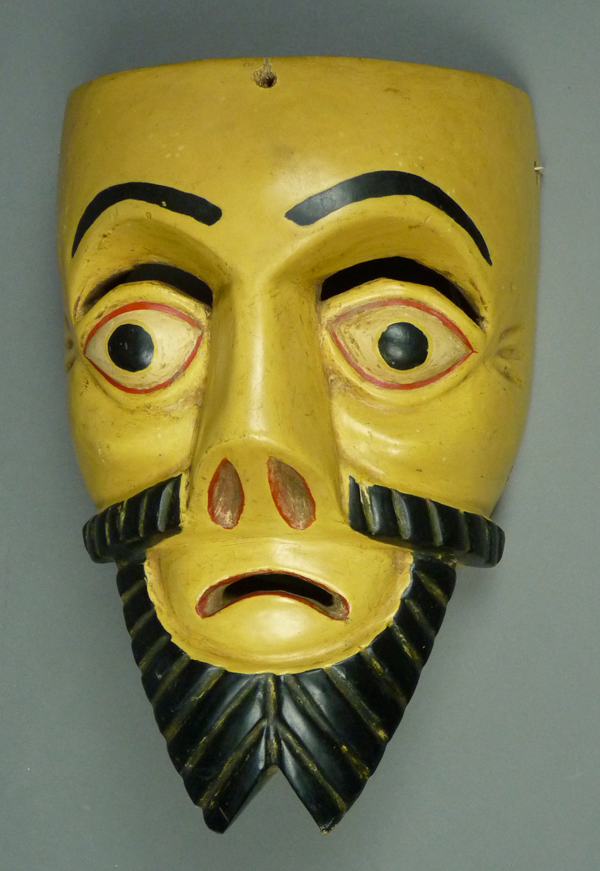

Here is a mask similar to those in Plate 32, from the collection of Charles Thurow. This is certainly a dramatic carving. This particular mask resembles the central statue at the Trevi Fountain, in Rome.