John Levin, a Mexican mask collector who lives in San Francisco, California, has sent photos of some of his masks that are from San Luis Potosí (SLP). I am pleased to share these with you. In his day job John is a screenwriter; he has just published a book of his plays, Three Plays By John F. Levin. If others would like to contribute photos for display on this site, I would be pleased to explore that with them.

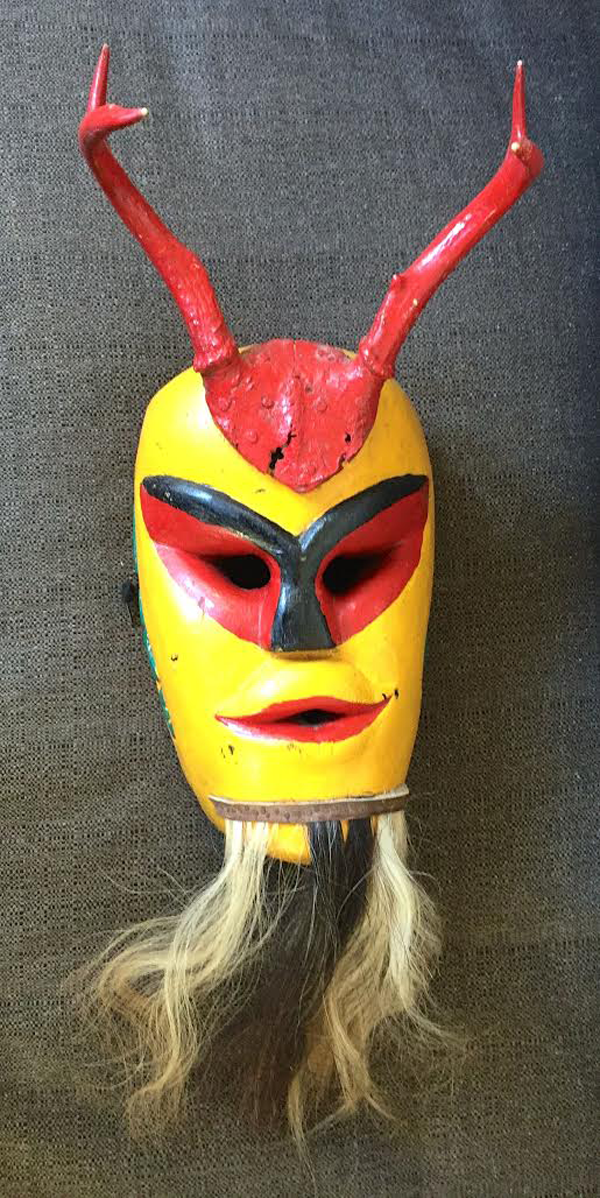

The first of these masks is an obvious devil, one of the Fariseos that perform during the drama of Semana Santa. Several aspects of this mask are notable. First, the features of the face are carefully carved, and enhanced by careful painting; I perceive the mask as having a glamorous feminine face. So I wonder if this is a Diablita, a female devil. Of course the beard argues against this, but that may have been applied by a dancer as an afterthought. Certainly there is a sharp contrast between this face and the faces of the brawlers in a recent post.