In November 2008 I purchased an attractive old female mask on Ebay™. The seller described it as a Zoque mask from the Mexican state of Chiapas. I was intrigued by that description and after winning the auction I asked the seller for more information. There was no reply. I concluded that this was one of those familiar situations where a seller is guessing about the identity of an object in order to pitch it. I like it a lot, whether correctly identified or not, but what is it really, I wondered. Then and now, a search of books and the Web did not reveal such a mask from Chiapas.

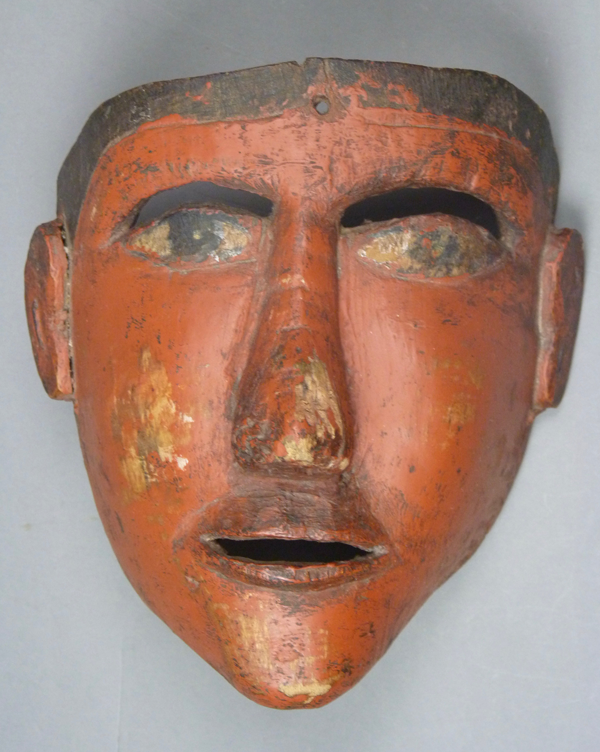

Ten years later, I decided to hazard a guess for myself. Here is the mask.

This is an old and heavily worn mask, judging from the patina on the front and the back. In general, it looks like a mask of Malinche from a Conquest dance in Guerrero. For example it has applied ears, something one often sees on masks in Guerrero. Also, this is a paint color that can be found on Tenochtli masks, a style of Conquest mask. In Donald Cordry’s book, Mexican Masks, there are dance photos and some masks from la Danza de Tonochtli, which demonstrate this resemblance. For example, plate 19 on page 16 shows a photo of a very old female mask of Abuela Teresa (Grandmother Theresa) from San Miguel Oapan, Guerrero. Other dance characters in this portrayal of conflict between Spanish forces and Native Americans include Cortez, Indian kings, and Malinche, Teresa’s daughter. The paint is entirely worn off of Teresa’s face, and there is no trace of red pigment. However, on page 34, plate 38, Cordry includes a photo of red faced Malinche masks from the Tenochtli dance; “both are painted red to signify lust and wantonness,” said Cordry. Then again, this color may simple be intended to identify an Indian character. A dance photo from Acatlán, Guerrero, on page 220 includes a pink-faced Malinche, who is wearing a feather headdress and carrying a bow and arrow.

You may recall that Malinche is sometimes viewed in Mexico as a traitor , because she helped Cortez to defeat the Aztec Indians, even though she was an Indian herself. This attitude leads Mexicans to portray her with disrespect. Cordry’s explanation of the color may reflect this attitude.