In his Masters Thesis of 1967 on Rio Mayo masks and carvers, James Griffith wrote about Plácido and Marcelo Alamea (pp. 105-107). Marcelo was Plácido’s son and both are deceased. In the Spring of 1965, when Griffith was working in the Rio Mayo region, Plácido was about 60 years old, and living in Jitombrumui, Sonora. He had danced as a Pascola, foot pain led him to retire, but he continued to play the violin at fiestas. “He also makes violins, harps, and masks, and has some reputation as a curandero,” wrote Griffith. Marcelo , who was living in Loma del Refugio, Sonora, was also a mask carver and a festival violinist. Griffith felt that father and son carved similar masks, as if there might be an Alamea family style. He described their masks as having “complex borders” and observed that ” six of the masks have horizontally flat faces with vertically convex cheeks.” When present those cheeks do provide one marker for masks carved by the Alameas, although some of their masks lack this feature.

Mexican Masks, by Donald Cordry, was published in 1980. In that book we find a photo of “Don Plácido” that was taken by Cordry in Antanguisa, Sonora in 1938 (plate 140, page 101); Placído was carving a mask and a completed mask was nearby. According to Leonardo Valdez, who had assembled a Museo (museum) collection of Mayo dance material in Etchojoa, Sonora, this Don Plácido was Plácido Alamea. Leonardo had one of Plácido’s harps on display in the Museo. Unfortunately I have been unable to locate Antanguisa. Griffith shows Jitombrumui on a map that indicates it lay 10 Km. to the west of Navojoa (and 10 km. west of Loma del Refugio, Marcelo’s village).

I visited Jim Griffith at his home near Tucson in 1990, and he kindly allowed me to photograph the masks he had collected during his research among the Mayo Indians of Sonora. At the time I wanted these photos as visual records of carver’s styles (a reference library), and I never sought his permission to publish those images. Since then Jim has donated those masks to the Arizona State Museum in Tucson, Arizona. At about the same time I obtained the book written by James Griffith and Felipe S. Molina, Old Men of the Fiesta:An Introduction to the Pascola Arts (1980), and I began visiting the Arizona State Museum’s Yaqui and Mayo collections. Through these experiences I discovered the masks of Plácido and Marcelo Alamea. Today I will focus on Plácido.

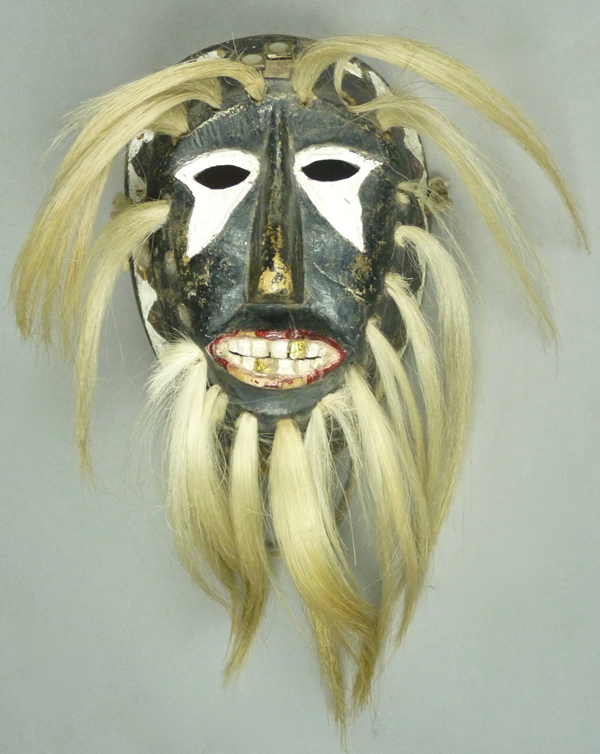

Here is one of the masks carved by Plácido Alamea that was collected by James Griffith during his research in 1965. What a beauty!

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/318629742362788611/

From the time that I first discovered Plácido’s classic mask style, I wanted one or more for my collection. Ultimately one doesn’t get to collect what they want, but what they encounter. I wasn’t able to buy a mask by Plácido until 10 years later, when Tom Kolaz offered to sell me one. As you will later see, this is a very unusual and interesting mask. Then, in around 2005 I obtained a more classic example, which I will show you first. I bought this mask from the John C. Hill Indian Arts Gallery in Scottsdale Arizona, with no provenance. While this mask exemplifies Plácido’s style, I am uncertain whether it was carved by Plácido or Marcelo.

On first glance, you may have noticed that this mask exhibits many generic Rio Mayo Pascola design elements, such as the chevron shaped wedges that flank the nose, a forehead cross composed of four triangles with their points together, a mouth like those on masks by Pancho Parra and Bonifacio Balmea, and hair bundles that frame the face in a circle. These are all typically found on Alamea masks. An unusual detail is the chin cross, which matches the one on the forehead, and appears to be original to the mask. The rims of the eyes were carved in relief, another common feature of masks by the Alameas.

An important detail that points to the Alameas is the nose design. On this mask, the bridge of the nose narrows to an extreme degree as it reaches the top of the mask.

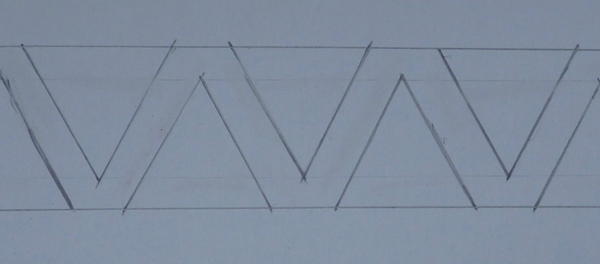

I am impressed by the interesting rim design that Plácido had used for many years. Here is a drawing of that design to compare with the rim design on this mask. Inscribed parallel lines anchor alternating triangles that are slightly separated from one another, creating the visual effect of triangles with double frames. Often the triangle with points facing towards the rim (or those facing up in this drawing) were painted one color, such as white or red, while those with points facing the cheeks were painted a contrasting color, and the zigzag strip separating the triangles might retain the background color, usually black of course.

This angle shot provides a good view of the characteristic Alamea rim design, with red triangles interlaced with white ones, but separated by a black zigzag element. In this instance, the laying out of the rim design is imprecise, which is one reason I am uncertain whether Plácido or Marcelo made the mask.

Noses by the Alameas tend to have either rounded or blunt ends.

The forehead and chin crosses have the same design, and the rim design has gaps for the placement of those crosses.

This mask is 7 inches tall, 5¾ inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The number on the back of this mask indicates that it had once been in the collection of Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazón, and appeared in their Mexican Mask show in 1981. I had initially met Leonardo Valdez at Jaled’s house in Azcapotzalco (a suburb of Mexico City), and Jaled displayed a group of Mayo Pascola masks on his bedroom wall, so I assumed that Jaled and Estela obtained their Mayo material from Leonardo. Jaled usually dipped an insect infested mask into kerosene to eliminate the infestation and arrest the damage. Such treatment causes a glazed surface. In this case one can see differential staining from contact with the faces of dancers, but this was further darkened by the kerosene.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Now I will show photos of the mask I purchased from Tom Kolaz in 1998. This one was more finely carved than the other and I feel certain that it was made by Plácido. Tom described it as a mask that had been “strongly reworked,” and he suspected that Marcelo might have played a hand in these modifications. It began fiesta life as a classic mask by Plácido Alamea, and elements of the original rim design can be observed. Probably the original rim design was much like the one on the first mask in today’s post, because where the paint is worn one can see red triangles shining through.

However, that design was painted over so that a more modern rim design could be installed. This new design featured an inlaid forehead cross composed of ½ inch brass squares with round imitation mother of pearl inserts; two of those squares remain. Those elements were undoubtedly commercial products that were adapted for this purpose. The rest of the inlaid new rim design was constructed from ½ inch squares of brass sheet that were probably hand cut with a jeweler’s saw from recycled brass cymbals. I had seen such cymbals at the workshop of Francisco Gamez, of Masiaca Sonora, when I visited him in the company of a group from the Arizona State Museum in April 2006. Francisco stated that the cymbals had been supplied by Barney Burns, mainly for the purpose of making round brass discs used in the Pascola’s hand rattles (senasom). Anyway, the brass rim design represented just another phase in the life of this mask.

In passing, I might add that this is the sort of mask that Tom Kolaz finds the most interesting, because such masks have been subject to such a variety of modifications and “improvements” over their years of use. The original mask became almost unrecognizable in the process.

Here is a Mayo senasom, hand carved from Catclaw wood (Acacia). Note the grooved brass disks that were cut from recycled brass cymbals. I don’t believe that it was ever used by a dancer, but this is the typical form preferred by Mayo Indians.

Later all the elements of the modern rim design were also painted over, and a simple rim design of alternating white and black triangles was substituted. Along the way the original chevron shaped wedges flanking the nose were replaced by triangular “tears” that dropped down from the eyes, a stylistic detail that I associate with Yaqui masks. Like the other mask, this one also has a ring of hair tufts around the face (although some are missing).

Here is a closer look at the nose, which tapers to a narrow point at the top.

The mouth was very finely carved, but it looks a little rough as the red nail polish has been flaking off the lips. Foil from cigarette packs emulates dental work on some of the teeth.

The nose on this mask has a delicate profile. In the following view from the side one can also observe some of the ½ inch brass squares that made up the second rim design, disguised by white paint.

There is another feature of Plácido Alamea’s pascola masks that is most easily seen in this side view—the cheeks are convex, meaning that they balloon out towards the front of the mask. In contrast most Rio Mayo Pascola mask cheeks are relatively flat in that dimension. On the other hand, some Alamea masks lack this feature.

On the top of the mask there are still two brass squares with mother of pearl inserts. There were probably five when these were installed. To the viewers left there are double diagonal lines from the original rim design. Then to the left of those lines one can see one of the ½ inch grooved brass squares, currently painted white. Still another of those squares may be seen to the right of the cross, nestled in additional horizontal and diagonal lines from the original rim design.

Likewise, three layers of rim design elements are visible in the photo that follows of the upper left corner of the mask. The characteristic double lines of the original rim design, which are difficult to see, shelter a painted over red triangle in the center of this photo. White painted squares on both sides are those hand-cut brass squares, covered by paint, and larger white triangles make up the most recent rim design.

All these elements appear again in this view of the right side of the mask. The grooves on the brass squares are visible, for instance, on the square adjacent to the strap. The deep groove to the right of that brass square was part of the original rim design.

And likewise at slightly greater magnification.

The chin of this mask has been rubbed bare of any finish, but it doesn’t seem that the rim design came this far, nor is there any evidence of a chin cross.

This mask is 7¼ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

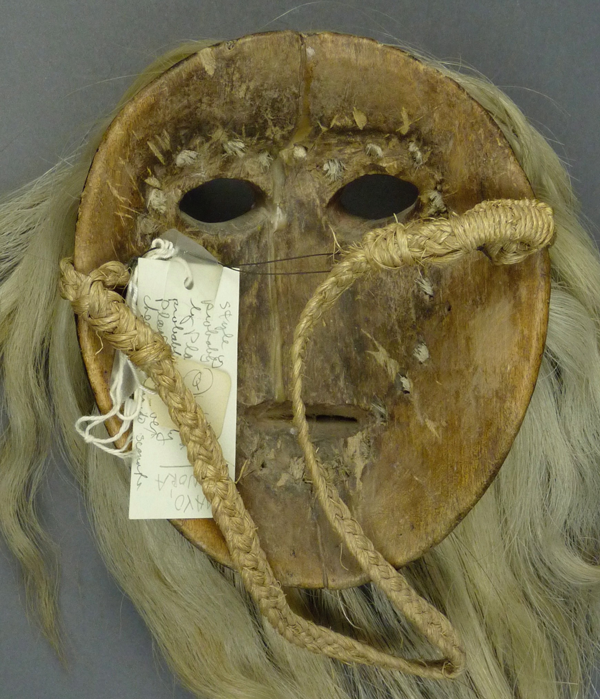

The back of this mask is stained a dark amber color from long use. There is an old cord strap that is likewise stained. This is a beautiful old mask that was heavily danced.

Now I will introduce some masks from another collection that are in Plácido Alamea’s style. I photographed all of the masks that follow when they were in the collection of Jerry Collings, in 2011, and he kindly gave me permission to publish them. I believe that they are no longer in his collection.

The first of these is a classic Plácido mask, and more finely carved than the opening mask in today’s post. It was collected in 1981 by Edmond Faubert, after allegedly having been danced for 20 years. Do notice the rim design that is visible across the top of the mask.

The upper end of the nose demonstrates the extreme taper that one associates with Placido’s style, although this is camouflaged by repainting at the top of the nose.

In profile, the nose on this mask is much like the one on the much modified mask that we just examined, and we see the same convex cheek design.

The forehead cross appears to be painted but not recessed.

This mask is 7 3/8 inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back of this mask is beautifully stained from use.

The next mask was collected by Roberto Ruiz in 1982. It was said to be 50 years old at the time of collection, and it was erroneously attributed to Pancho Parra. This is indeed a nose that could bring either Pancho or Plácido to mind, but the rim design leads us to Plácido, as do the painted arcs over the mouth. We see yet another ring of hair bundles on this mask.

In the side view one sees Plácido’s rounded convex cheek, and another beautiful nose.

The forehead cross appears to have been constructed with triangles of mirror glass, which have almost all been lost. The rim design is, as earlier noted, in the Alamea style.

The relief carved rims around the eyes are particularly beautiful.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

This mask had split down the center, and is lashed together with wires.. This is, of course, another heavily stained back.

At first glance this next mask looks a little different from the ones we have just examined. Then I saw that it had the same relief carved rims around the eyes as the last mask, and the nose tapers dramatically. It also has convex cheeks. It was purchased as an anonymous mask that dated to about 1950, and it was attributed to Plácido by an early collector.

There is a ring of hair bundles around the face.

The profile of the nose does look like Plácido’s, except for the hump at the top, and in this view on can see the convex cheek.

The rim design is attractive, although it does not make one think of Plácido’s classic design.

There is a carved recessed cross on the chin, which is difficult to see because a crack in the wood literally bisects the cross.

This mask is 7¼ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The back is very darkly stained. The crack that distorts the chin cross is visible on the back as well.

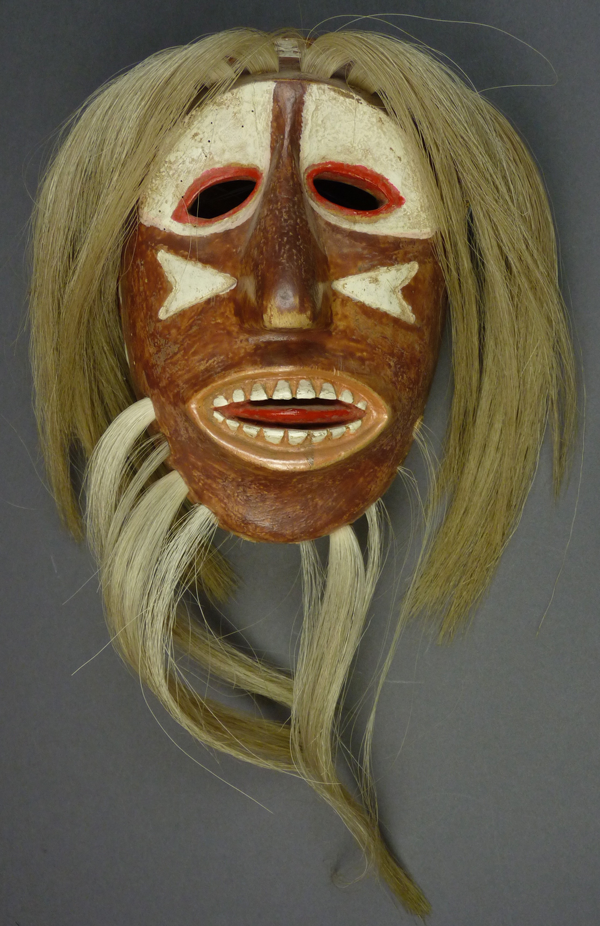

This brown faced mask was collected in 1980. The initial tag seems to say that it might have been made by Carlos Arcia, but the mask was subsequently attributed to Plácido Alamea.

Certainly the nose and the convex cheeks suggest that Plácido was the carver, even though the rim design is not in his classic style.

This is an attractive mask of an Indio (Indian).

The rims of the eyes are carved in relief.

A close look at the hair bundles that make up the eyebrows reveals that they are held in place by wooden pegs.

This mask is 7 inches tall, 5¾ inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back is moderately stained from use. There is no string on the back to hold the hair bundles. They are only being held by the pegs.

I am including this next (and last) mask despite my uncertainty that it was carved by Plácido Alamea. Rather, I perceive it as a remarkable mask that either copies or alters Plácido’s style in some respects. It was collected by Roberto Ruiz for Barney Burns in the spring of 1982, after four year’s use, in Huayparin (Guayparín), while it was said to have been made in Pozo Dulce, Sonora.

You might immediately notice that the nose does not taper; instead it has a stable width like some noses carved by Bonifacio Balmea. However, on further examination, one realizes that this is a replacement nose, a repair. I call your attention to the nail hole at the top of the nose. In the absence of the original nose, we will have greater difficulty identifying the carver with certainty.

More generally, the red color and the elaborate marks on the cheeks announce that this mask depicts an “Apache.” a type that we also see in Yaqui masks.

The rim design on this mask copies those of the Alameas, although the black triangles appear to have been applied, glued on. The forehead cross was also modified by an applied addition. Now please turn your attention to the nose in this side view photo. The paint on the nose does not match that on the face, and the nares appear to have been constructed of wood filler, all further evidence that the nose is a replacement.

The joint where the top of the replacement nose meets the forehead is easy to see in this overhead view.

From below we have a better view of the wood filler that was applied around the base of the nose, and there is a paper thin gap where the replacement nose meets the area over the upper lip.

This mask is 7 1/8 inches tall, 5¼ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

Looking at the back in the area between the eyes, we find another nail hole. The hole behind the mouth is strange; is it for ventilation? The back is heavily stained from use.

I hope that you have liked seeing these exquisite masks by Plácido and perhaps others. Next week we will see masks by his son, Marcelo Alamea.

Bryan Stevens