Today’s subjects are masks from the area of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, Michoacán that can be used in two distinctly different dances. On Christmas Eve, immediately following the Midnight Mass, they are worn during the performance in the church of the Danza de los Viejos (the “Old Ones”), and such performances continue the next day. Then on January 7th and 8th they are used in the Dance of the Curpites. In nearby towns it is the well known Viejito (Little Old Men) masks that sometimes play these dual roles, but always with the Viejitos or Little Old Men name. In an attempt to keep things clear, I will refer to Curpite masks when I mean masks that can dance as Viejos or Curpites.

Here is a typical Curpite mask in the style similar to that found in Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, which I purchased on EBay™ in 2005. It came without provenance, however, it resembles a mask in one of Janet Brody Esser’s books—Máscaras Ceremoniales de los Tarascos de la Sierra de Michoacán (1984, page 61, Figura 6). That mask was carved by Luis Contreras of Neuvo San Juan Parangaricutiro in 1974.

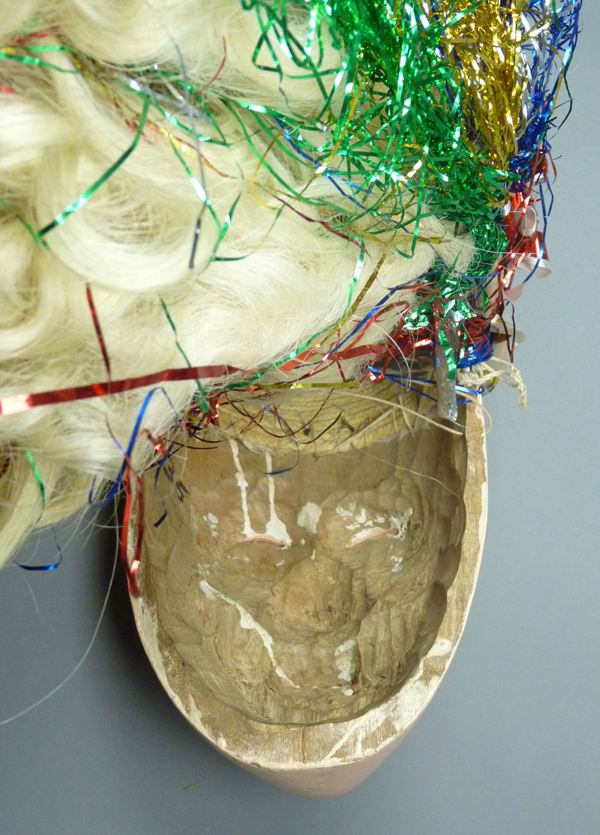

Here is that EBay mask. It is handsome and very well carved. There is an attached wig, of horsetail mounted on the crown of an old hat, and this is decorated with tinsel, ribbons and a square mirror, all typical features of a Viejo or Curpite mask.

A Curpite mask always has a male face. In Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro and some other villages, the Curpite mask will have a mustache. In this case, and probably often, the Curpite mask will have a mustache carved in relief. The mustache on this mask is particularly beautiful.

The masks of the Viejos, including those of the leaders (Tarépiti and Maringuilla), are usually finely finished and painted. The eyes can be carved and painted, as in this case, or constructed from recycled glass with painted details (some with glass eyes follow). Note the finely carved vision openings over the eyes. The open mouth with teeth is an unusual feature for the Curpite masks from Nuevo San Juan, and may indicate that this mask is from another nearby town, although such a mouth can be seen on Tarépiti masks, as you will soon see. None of the masks worn by these Viejos have ears.

The headdress is made of horsetails attached to the crown of a hat, and then ornamented with tinsel and ribbons. This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4½ inches deep.

The back seems unstained or only mildly stained and the crown of the hat looks new. It is possible that this mask was never danced.

The Viejos and then the Curpites Dances share two leading performers, Tarépiti (who is also called Grandfather or San José), and Maringuilla (“Little Mary”), a representation it seems of the Virgin Mary. All of the Old Ones or Curpites dancers are depicted as Caucasian. In the dance of the Viejos, those two figures and their corp of Viejos exemplify perfection and nobility. In the Dance of the Curpites, on the other hand, these dance leaders behave less seriously and the Curpites (supplicants) are frankly playful. The Curpites often seem like show-offs or dandies, and there is more than a passing resemblance between these Curpites and the Catrines found in neighboring Tlaxcala. All of these Viejo/Curpite characters dance in a highly stylized manner that clearly reflects European dancing introduced by the Spanish. This style, Zapateado, resembles tap and flamenco dancing; the goal is to dance with such subtle movement that the dancer’s feet sometimes hardly appear to move.

Janet Brody Esser has in various publications described her observation that in the mountain towns of Michoacán masked characters seem to represent polar extremes, portraying- the “beautiful” and the “ugly”. By “beautiful”, she refers to noble, idealized figures that personify right behavior. In contrast, other figures behave in an “ugly” fashion, through imitation of intoxication, promiscuity, lack of cleanliness, and chaotic behavior; they are literally called “feos” (uglies). In Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, the Viejos and Curpites dance in apposition to the Viejos Feos (literally “uglies”).

The performance of dances that compare these contrasting mores and values is apparently meant to teach a moral lesson to the young. (To learn more, see Esser’s PhD thesis, Winter Ceremonial Masks of the Tarascan Sierra, Michoacan, Mexico, in 2 parts. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms, 1978, Vol.1, pages 10 and 71).

The beautiful/ugly dichotomy suggested by Esser’s observations has proven to be a valuable tool for me in my efforts to understand masks from all over Mexico. I have discovered that there are virtually no masks that represent the common man as a neutral figure, instead a dance character is either depicted as noble or badly behaved. Occasionally one encounters a clown character that teeters between these two poles before demonstrating his polarity.

In Behind The Mask in Mexico (1988, pages 106-141 ), a book edited by Janet Brody Esser, one finds descriptions of dance performances in the Mexican state of Michoacán that explicitly reflect the tension between the beautiful versus the ugly. The dance of the Viejos or Viejitos (“Old Ones”) and the Dance of the Turía (Blackman) are examples of dances with idealized roles. These particular dance figures appear to be unique to Michoacán. There are other dances found throughout Mexico that feature Viejos (old men), but those characters behave differently.

Here is a YouTube™ video of Tarépiti and Maringuilla dancing, accompanied by the corps of Curpites. Tarépiti usually carries a staff with a wooden carving of an animal head on top. According to Esser, this is the head of a donkey, as if a reference to the Virgin Mary riding on a donkey, accompanied by Saint Joseph. In recent videos, this staff appears to carry a horse’s head.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dk62WkFj7WI

In the dance of the Turía (called Negritos in Spanish and the dance of the Blackman in English), the dancers wear elegant business suits, black masks, and elaborate headdresses. This dance will be the subject of later posts, but I mention it because one of those black-faced masks will be included later in today’s discussion.

Now we will examine a group of four masks that were in the collection of Robin and Barbara Cleaver for about 20 years before they sold them to the writer in 2004. These masks were thought to date to the 1950s, and they are in the style of masks carved by Antonio Saldaña of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, Michoacán. That town replaced the older town of San Juan Parangaricutiro that was destroyed by the Parícutin volcano in 1943. Three of today’s masks are in the style of those used in the Curpites dance of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro while the fourth would have been found in the Danza de los Negritos or Blackmen in San Lorenzo, Michoacán. All four have wigs made from horsetail that have been decorated with tinsel and ribbons.

The first of these was worn by Tarépiti (also called Grandfather and Saint Joseph).

Like the Curpite mask that introduced this post, this Tarépiti mask is very well carved and carefully decorated.

Tarépiti always has a full beard. He usually lacks ears. These eyes are carved in the wood.

This mask is 10 inches tall, 5¼ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The back of this mask is smooth and stained from long use. There are drilled nostrils for ventilation.

The second mask was worn by Maringuilla (Little Mary). Like Tarépiti, the Maringuilla character is an idealized personage, meant to personify what is right, noble, and beautiful.

She too wears long and colorful ribbons, either tied to her hair or hanging from the edge of a straw hat.

She has delicate crescent shaped vision slits over the eyes. These eyes are glass.

Maringuilla’s face is meant to portray idealized feminine beauty. This mask is 7 inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 4½ inches deep.

The back of this Maringuilla mask is heavily stained from use.

The third mask is one that would have been worn by one of the Viejo or Curpite dancers. However this mask was actually made to be worn by Maringuilla and then converted to a Viejo mask with a little black paint for the mustache and around the eyes. Before that conversion, this mask portrayed a woman whose face was as beautiful as that of the last mask.

This mask has glass eyes, which were hand made by melting recycled commercial glass (typically bottle glass).

Here is a side view of this mask, followed by an altered version where half the mustache has been erased using a photo editing program

In this pair of photos one sees the power of a little paint.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

The back of this mask is heavily stained from extended use, first as Maringuilla and later as a Curpite.

One might wonder why such a beautiful mask would be converted to a Curpite. Although the reason may never be known, still one can speculate. Both Maringuilla and the Curpites are portrayed by male dancers. More pointedly the Curpites dancers are usually adolescents or young men, and their performance in the Curpite role is specifically directed to their actual or potential sweethearts, as if they are tropical birds with colorful feathers and elaborate instinctive courtship routines. If you were a young man and a relative gave you a Maringuilla mask, would you use it as received or convert it to an instrument of courtship?

The last mask in this quartet also portrays the face of a woman. In fact, according to Janet Esser, black-faced female masks are worn to dance with the male Blackman dancers in San Lorenzo, Michoacán, and these are also called Maringuillas. Unmasked Indian women, called Guares, also join in dancing with the men wearing pink and black-faced Maringuilla masks (see pages 112-133, plates 70, 74, 75, and 80 in Behind the Mask in Mexico).

I only realized that this was meant to be the face of Maringuilla in the course of paying such close attention to this mask in comparison to the two that preceded it in this post. There are also special clues. For example, the Blackman masks, which portray black-faced males, usually have relief carved ears that are carefully crafted, while the Black Maringuilla masks lack any sign of ears, just as the pink Maringuilla masks have none. The absence of ears is probably a reliable marker for female gender on a black-faced mask from San Lorenzo, and perhaps from some other places. These eyes are carved, not glass.

The headdress on this example creates ambiguity however. In Esser’s dance photos these Black Maringuillas often wear a charming woven straw hat that was obviously meant for a woman.

The Blackman masks do not have mustaches to aid in this comparison, but they do typically have coarse features, as you will see in a later post. This mask has the delicate face of a girl. It is 7½ inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

This is yet another mask with heavy staining from use.

In the coming weeks we will survey additional examples of Tarépiti, Maringuilla, and Curpites masks.

I think the bearded Tarepiti mask is by Antonio Saldena, the most famous of the Nuevo San Juan traditional mask carvers.