In September of 2012 I published a book—Mexican Masks and Puppets—that was meant to honor the master carvers in a remote area of Mexico called the Sierra de Puebla and to link these carvers to their heretofore anonymous masks. One of the most talented and exciting of those carvers was Magno León. Today I will discuss the initial group of masks that served as my introduction to this carver. This will provide us with the necessary information to discuss three additional masks by this carver in next week’s post; these came to my attention after my book was published and were identified as his work based on the earlier documented masks.

Traveling in the Sierra de Puebla in March, 2010 with Vernon Kostohryz and Carlos Moreno Vásquez, we discovered a remarkable anonymous mask. It appeared to have the sagging face of a dead person, reminding us of characters in old horror films such as the Ghoul, played by Boris Karloff in the film of that name in 1933, or perhaps some other role played by Lon Chaney. On reflection, this mask didn’t seem to duplicate any of those faces; instead it was an original creation by some unknown artist. The mask was said to have been danced for Carnaval (Mardi Gras) for more than fifty years. Here are photos of this Ghoul mask.

Note the strange sagging eyes, as if the person is barely awake. Of course you can’t miss the aged surface of the paint.

This is an expressionless or vacant face, mysteriously drained of human feeling.

The Ghoul mask is 10 inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 4½ inches deep. The back is dark with age.

I have to say that this mask is so unusual, in comparison to other masks by Magno León, that there is only a little to note that is characteristic of his hand; one typical detail is the curved hollowing of the surfaces below the vision slits that is particularly easy to see on the left side, along with the recessed area for the dancer’s nose. More subtle is the bowl-shaped hollowing to accommodate the dancer’s mouth. Often this hollowing is more dramatic on other Magno masks. Of course the back also reveals remarkable staining from long and intensive use.

At around that time we were also told of an old set of masks for the Santiagueros dance that was owned by someone in the next town—Hueytlalpan, Puebla. We traveled there, asked around, but we were unable to find the masks.

Carlos Moreno Vásquez returned to the area in the following months, and solved both riddles. He learned that the Ghoul mask had been carved by Magno León, and that the Santiaguero masks were in Olintla, the town above Hueytlalpan. Actually these were masks for the Hormegas dance, a variant of the Danza de los Santiagueros; several of the masks in the Hormegas dance set turned out to have also been carved by Magno León. Armed with this information, Carlos was able to track down some of Magno León’s relatives, including his second wife and several of his grown children. They informed him that Magno had also been a talented santero, a carver of wooden saints. Carlos purchased several masks from family members and others from dancers in Zapotitlán. Soon we had a useful study collection at our disposal.

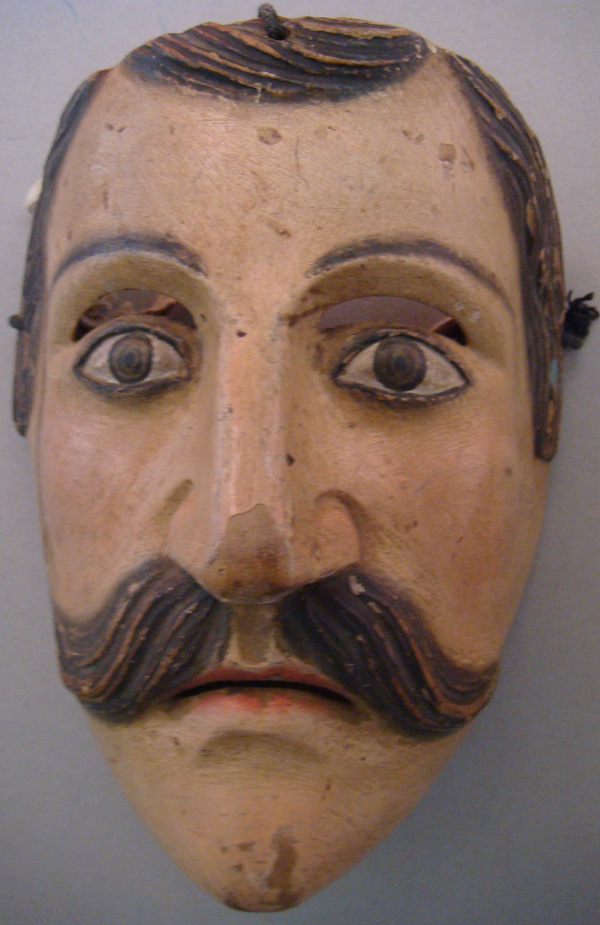

The most attractive of the newly found masks were male and female Huehue masks for the Huehues dance. They were exquisitely carved and are probably the finest masks that I have seen from this area, although both were flawed in the same unexpected way. The male mask had no visible ears, as if those features were completely covered by his hair, while the female’s ears were depicted as if only partly exposed, so that only her earlobes were visible. In a region where almost every Huehue mask is carved with elaborate ears that reveal the identity of the maker, these masks did not supply that evidence. The photos of these masks are courtesy of Vernon Kostohyz. They are currently in private collections.

This mask is 7½ inches tall and 6½ inches wide.

Here one can see the typical features of Magno León’s style for carving the back of a mask. Oval recessed areas frame the openings for vision, there is a generous recessed area to accommodate the dancer’s nose, and a bowl shaped depression at mouth level creates space for the dancer’s lips. J.L.L. was the owner of this pair of masks.

This female Huehue or Tejonero mask by Magno León is exquisite, one of the most beautiful masks that I have ever seen. It is obvious that Magno was a santero, because this mask is carved with the fine features of a saint.

This mask is 7 inches tall and 6 inches wide.

Here is the half covered ear.

The back of the female Huehue mask has the same design as the back of the male mask.

Later Carlos found another male Huehue mask that was said to have been carved by Magno; this came directly from the carver’s family. I immediately added that mask to my collection because it combined Magno’s careful carving with the inclusion of full ears. On the negative side, this mask had an applied mustache that was attached by nails, rather than the elegant one that had been carved in place on the first mask. I comforted myself with the realization that this applied mustache may have been provided by Magno to address changing tastes. It was particularly obvious when I studied Huehue masks from nearby areas such as Olintla, Puebla that there had been a flurry of such mustache transplants in recent decades, while earlier Huehue masks of males were often depicted without any facial hair beyond sideburns.

This mask is 7½ inches tall and 7 inches wide.

Here is the beautiful ear design used by Magno León, framed by carefully carved hair.

This back has the same design as the last two.

With these three Huehue masks before us we can begin to recognize their common features. Since the back of third mask is directly before us, why don’t we start there. All three masks look exactly the same on the back, with recessed oval ares around the eyes, a recessed area ventilated by two holes to accommodate the dancer’s nose, and a bowl-shaped recessed area above the chin to create space for the dancer’s mouth. Shifting to the frontal views, we will notice that the first two masks are highly sophisticated in their detailing while the third has similar features that seem less refined. All three masks have curved or arching visions slits, with relief-carved eyes underneath. These vision openings have carefully shaped rounded ends, although the frontal view gives the impression that the lateral ends of the slits are squared off. This is a strange but frequent feature. All three have carefully carved hair and the first has a mustache to match. Each has the same nose and the same groove below the nose. Although all three share the same chin contour, the first two have subtle enhancements that the third lacks. Moving to the side views, only the third mask has complete ears, but the female Huehue mask has partial ears of the same design.

I told you that Magno León was a santero. Here are two carvings by Magno that Carlos Moreno Vasquéz obtained directly from Magno’s wife.

The first is the hand of a saint. I suspect that it depicts the hand of Christ, blessing the crowd during his preaching before the crucifixion. This symbol of Christ is often accompanied by a text—”I am the way…”

The length of this hand is 9 inches and the spread from thumb tip to little finger is 4 inches.

This hand was probably mounted upright on a stand, although I received it in this detached state.

The second carving is the head of a child. It demonstrates the same exquisite detailed carving that we saw on the Huehue couple. The ears are more naturalistic and less stylized than those on Magno’s masks.

The entire carving is 7 inches tall, the head is 5½ inches wide, and 5 inches in depth.

Next week we will examine three masks that were found without any provenance. By comparing them to those we looked at today we can establish that Magno León was their maker.

Thanks for your website and particularly for culling the best of the i-phone type videos of the dances. I have been cataloguing my own collection of Mexcian dance masks and have come across a number of videos and they are indeed a great resource.

Best Regards, JOhn

Thank you John. It has been a revelation to me to discover the sudden availability, in the last few years, of remarkable videos that shed a lot of light on dances and masks.

Bryan Stevens

Estoy impáctala yo conocí al señor un verdadero artista , lo conocí cuando era pequeña y mi tío tiene varias cosas de él. Ojalá llegue a ser reconocido como se lo merece .