The Mayo Indians live in two adjacent Mexican states, Sonora and Sinaloa. Those in Sonora live in towns along the Rio Mayo, while those in Sinaloa live along the Rio Fuerte. There is apparently just enough distance between these two areas to have allowed differences to develop between their traditions. However we know so little about these differences. One obvious detail is that historically the Mayo Pascolas in Sonora have only rarely used animal faced Pascola masks, while those in Sinaloa have embraced Goat faced masks since the middle of the 20th century and perhaps for much longer. Therefore, as we turn our attention to Mayo Pascola masks from the Rio Fuerte towns we will see a mixture of Human faced and Goat faced masks. We will also see again a profusion of made for sale masks that don’t adhere to such traditions.

Much of what we do know about Sinaloa Mayo mask traditions has resulted from the activities of traders such as Barney Burns and Mahina Drees. I introduced them in my post of August 22, 2016. Here is a link to that post.

https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=6930#more-6930

As you may recall, Barney and Mahina encouraged Indians in a number of Northern Mexican states to produce their traditional arts and crafts for a North American audience, thus providing these subsistence farmers access to cash and modern materials that requires cash to acquire. Then they sold these crafts to Indian Arts dealers in the United States. Along the way, they also collected objects that they found particularly interesting, such as danced masks. One of the Sinaloa carvers, Saturnino Valenzuela, stands out as a prolific and talented artist, so I will begin with his masks. Today we will examine four of those that I purchased from Tom Kolaz in 1998. Three of the four had been danced. These masks served as my introduction to this carver.

The first of these has a very long beard.

Otherwise this example is very representative of Saturnino’s style. Almost all of his masks have:

1. this rim design of small gouged triangles painted in alternating colors,

2. a forehead cross that has been carved in relief, and

3. additional decorative elements that are carved in relief, such as flowers, stems of flowers, and even flower pots. This mask has flowers with stems on the cheeks.

Saturnino’s method of carving elements in relief is to carefully carve a recessed area around the element that tapers to blend in with the surrounding surfaces.

Saturnino carves some elements, such as horns and extended tongues, so that there is space between the element and the adjacent surface of the mask. However, he may then anchor the tip of the elevated element by carving it in contact with the face. On this mask, the tongue is managed that way. So Saturnino cleverly carves elaborate elements that are strong and unlikely to break easily.

This mask is 7¼ inches tall, 4¾ inches wide, and 2¾ inches deep.

The back of this mask is mildly stained from use, and the ribbon (strap) is mildly frayed.

The second mask has a goat’s face, complete with relief carved horns. This mask was apparently never danced. It was collected by Barney Burns and Mahina Drees in 1989.

We find the same rim design. Like the flowers, the goat’s ears are also carved in relief.

Note the hollow, daylight areas under the goat horns, in contrast to the lack of separation of the tips of the horns and the forehead.

Saturnino consistently carves a Maltese cross on the forehead.

The mouth, teeth, and tongue are carefully carved.

This mask is 7 inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back of this mask does not appear to have been stained from use. This very smooth back is typical of those carved by Saturnino.

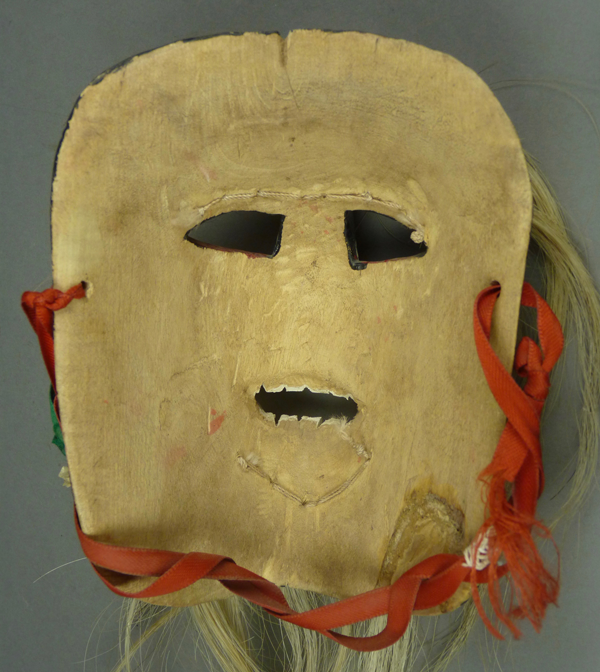

The third mask was collected by Barney T. Burns in 1990, after it had been danced for 8 months.

The paper flower, which was collected with the mask, had been tied to the dancer’s hair.

Like the first mask, this one also has relief carved flowere with stems on the cheeks.

Saturnino’s typical rim design is very easily seen on this mask.

The rim design on Saturnino’s masks typically continues around the shin, as in this case.

This mask is 6¾ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back has moderate staining from use.

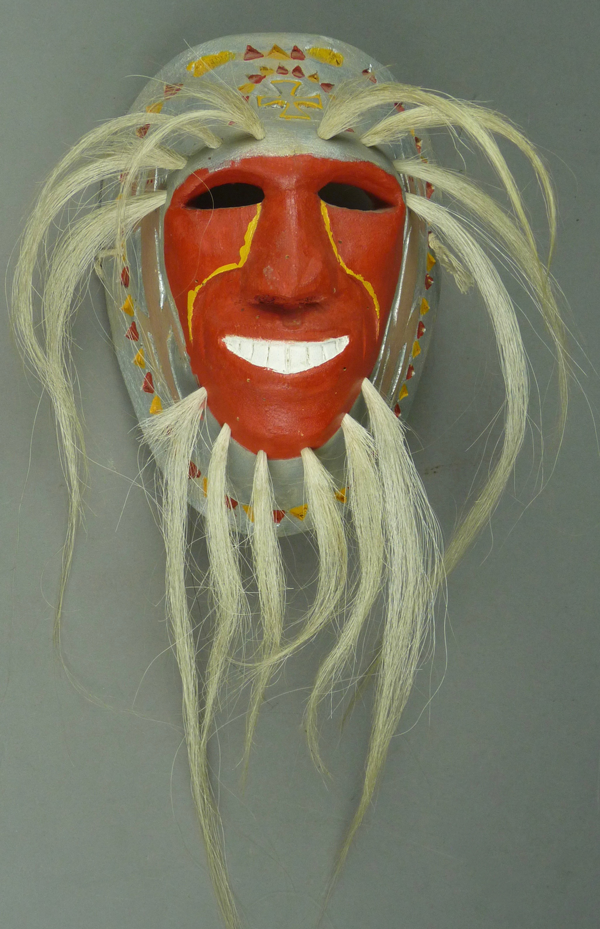

The last of these masks was carved in 1990. Somehow it was danced by Billy Montoya, a Yaqui Pascola dancer, at Barrio Libre (39th street community, South Tucson Arizona) in 1991.

This is an “Apache” face. The silver paint is striking.

There are relief carved lizards on the cheeks.

The forehead cross is ringed by an arch that echos the rim design.

This mask is 7¾ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back demonstrates mild staining from use.

Next week I will show you more masks by Saturnino Valenzuela.

Bryan Stevens