This week we will examine the masks and other costume elements that are worn by the Santiaguero dancers.

I should begin with a brief discussion about names. This dance can be called the dance of the Santiagos or the dance of the Santiagueros. Either of these names seems to mean “a follower of Saint James, or Santiago.” Therefore the mask worn by one of these characters can be called a Santiago mask or a Santiaguero mask. I prefer to speak of Santiagueros and Santiaguero masks to avoid confusion, because “Santiago mask” can be easily misunderstood as a reference to a mask worn by Santiago himself. This ambiguity leads sellers and collectors to think of all Santiaguero masks as having been worn by Santiago, even though this character rarely wears a mask in contemporary performances.

Last week I included a dance photo of Santiago. Here is another Santiago, preparing to dance, in the town of Zoatecpan, Puebla.

As usual, this Santiago has an elaborate hat and costume, he wears a wooden dance horse at his waist, and he does not wear a mask. In one hand he carries a wooden cross, which is barely visible behind the horse’s head. He would carry a wooden sword in his other hand, but this dancer hadn’t picked up his sword at the time of the photo, as the dance hadn’t started.

Last week I introduced the dance of the Santiagueros. I will briefly summarize my remarks from that post. This dance portrays the interaction between Santiago Caballero (who is said to be the reincarnation of Saint James the Apostle, returning as an archangel and mounted on a white stallion), a group of Santiaguero dancers led by General Sabario, and a group of Pilato dancers (the Pilatos), led by Pilato El Presidente (who is sometimes represented as Satan or as Satan disguised as a human). The Santiaguero dancers see themselves as “soldiers of the sun”, true Christians who serve an enhanced image of Christ—”Christ/Sun”—while they appear to view their Spanish conquerors as essentially failed Christians, whose actions are the opposite of what Christ advocated; in the past these views were apparently secret. With this in mind, one can look beyond the appearance of this dance as a description of events in the distant past to imagine another purpose, the performance of a nonverbal prayer to God by the Indians of the Sierra de Puebla for justice and relief from oppression in the present moment.

Next you will see a staged photograph of a Santiaguero dancer in the town of Buenavista, Puebla, to provide a comprehensive view of the usual Santiaguero mask, costume, and dance accessories. He is carrying the Mexican flag.

The dancer is wearing a typical Santiaguero mask. I call your attention to the white cotton ruffle that is attached to the chin of the mask; this is called a cantunga, and is meant to simulate a beard. Also note that the mask is worn on the forehead and not over the face. A mask carver in nearby Cuetzalan, Puebla, told Max Harris that this position symbolizes the orientation of the dancer; he is looking up at the sun, at Christ/Sun. The silver (or gold) painted brows and mustache on the mask symbolize the light of the sun. The dancer is wearing an elaborate headdress, the morión, on the back of his head. This is made of colored paper over a wooden frame, and decorated with paper flowers, bundles of bristles, and colored plumes.

Morión is a name that was originally used for the steel helmets of a similar shape that were worn by medieval Spanish soldiers. Here is such a morión, courtesy of Vernon Kostohryz.

The Santiaguero dancer is also wearing cascabeles, an apron or halter of cast brass bells of the type that were once called sleigh bells in North America. This photo shows the halter type, while the dancer is wearing the apron style.

In his right hand the dancer is carrying a dance wand and a chimal. The chimal is a symbolic weapon carried by both the Santiagueros and the Pilatos. As you will see in a subsequent post about Pilato and the Pilatos, those dancers pound the chimal against the blades of their wooden swords to indicate bellicosity. Here is an old and worn chimal.

Here are the dance wand and chimal that you just saw in the hand of the Santiaguero dancer.

General Sabario, the leader of the Santiagueros, is often the one to carry a sun shield, an obvious clue to the true allegiance of the Santiagueros. But sometimes informants state that the sun shield is carried by another Santiaguero. Three examples of these sun shields follow, and you saw another in my post about the Book Trip. Note that the color of the sun’s face on these shields is more or less the same as the color of the Santiaguero masks.

This is a sun shield that was made by Roberto Villegas Santiago. I purchased it from him before it was used. It is 8½ inches in diameter.

Like most sun shields, that of Roberto Villegas has a wooden handle on the back.

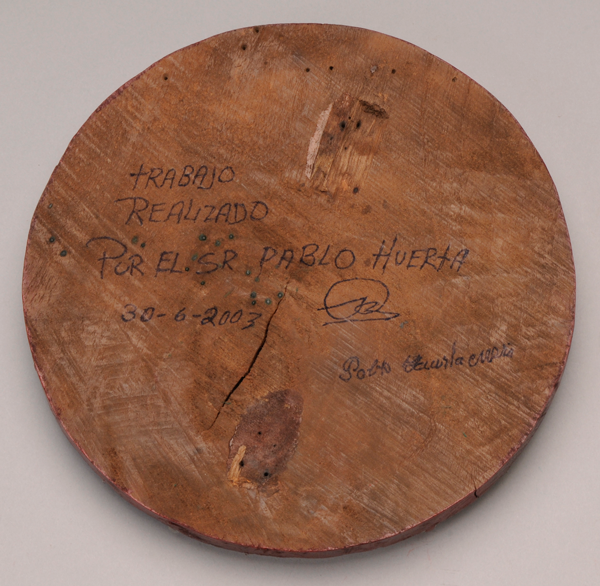

The next shield was made by Pablo Huerta Mora of Cuetzalan, Puebla, in 2003. I arranged through Carlos Moreno Vásquez to buy it from Pablo in 2010. It had never been used.

Pablo took pains to sign and date this shield upon its completion. There was a handle but it was subsequently removed and then lost. It is 9 inches in diameter.

The third sun shield was made by Benito Juárez Figueroa, a figure who is well known to you by now from prior posts. This shield was part of the set used for the Hormegas dance in Olintla, Puebla, and it was said to have been carried by “Callyn” (Callintsin, the son of Santiago in these dances).

The very formal handle on the back of this shield was attached by wooden pegs. It is 8½ inches in diameter.

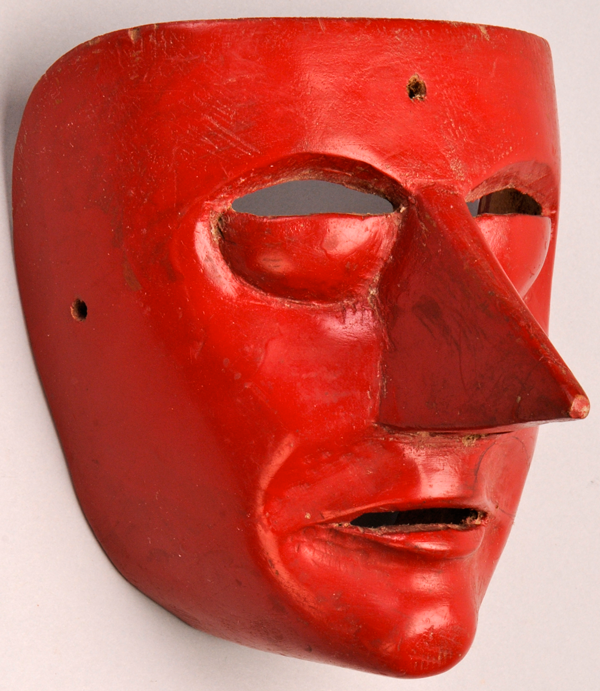

Now I will show an assortment of Santiaguero masks. You will see that these are mainly different from the Hormega masks because they have more substantial, triangle shaped noses, rather than the Pinocchio type noses of the Hormegas.

The first of these Santiaguero masks was made by Roberto Villegas Santiago. He copied an old Hormega mask that had been made by his late friend, Benito Juárez Figueroa. Although Benito’s Hormega mask lacked ears, Roberto included his ear design in the copy.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 5 inches in depth.

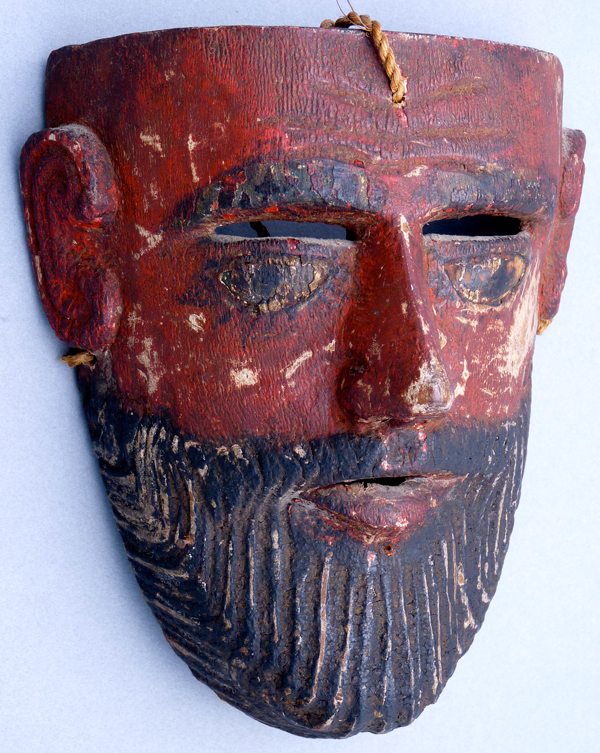

The next mask is one that was actually carved by Benito Juárez Figueroa. It is so elaborate, compared to the majority of Santiaguero masks, that I suspect it of being a mask that was worn by Santiago.

This mask is 9½ inches tall, 7 inches wide, and 4¼ inches in depth.

In the Sierra de Puebla masks are often stored in the rafters above the room in the house that serves as the kitchen. The smoke from the cooking fireplace is intended to protect them from damaging insects. However other insects sometimes take up residence in such stored belongings and the back of this mask has been stained by such invaders, perhaps moths.

Now I will show a variety of additional Santiaguero masks. The first of these was carved by Alejandro Dominguez, of Xochimilco, Puebla. There is an entire set of these masks being danced in Sabanas de Xalostoc, Veracruz. You met the Caporal of that Santiaguero group, José Aparicio García, in my post about “The Book Trip,” and his son posed for the camera with a mask identical to this one. This mask is 7¾ inches tall, 6¼ inches wide, and 5½ inches in depth.

The second mask was carved by Pedro Hernández Bautista of Buenavista, Puebla. I purchased it from the carver. It is 7 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4½ inches deep.

This third mask was carved by the late Pedro Huerta Mora of Cuetzalan, Puebla, the brother of Pablo Huerta Mora. It is 6¾ inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 5½ inches in depth.

The fourth mask in this series was carved by Manuel Aldana Valencia, otherwise known as Don Lillo, of Coxquihui, Veracruz. This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6¾ inches wide, and 6½ inches in depth. In the Book Trip post, Señor Miguel Juan Galindo (of Coxquihui) stands next to three Santiaguero masks that were carved by José González Galindo; one of these also has this white ring around the nose. This seems to be a local feature, probably meant to identify a particular Santiaguero character such as General Sabario? This blog forces me to notice such details that I hadn’t previously thought about.

This mask was carved by Ernesto Tóral Hilario, of San Miguel Tzinacapan, Puebla. This mask is 7 inches tall, 5¾ inches wide, and 5½ inches in depth.

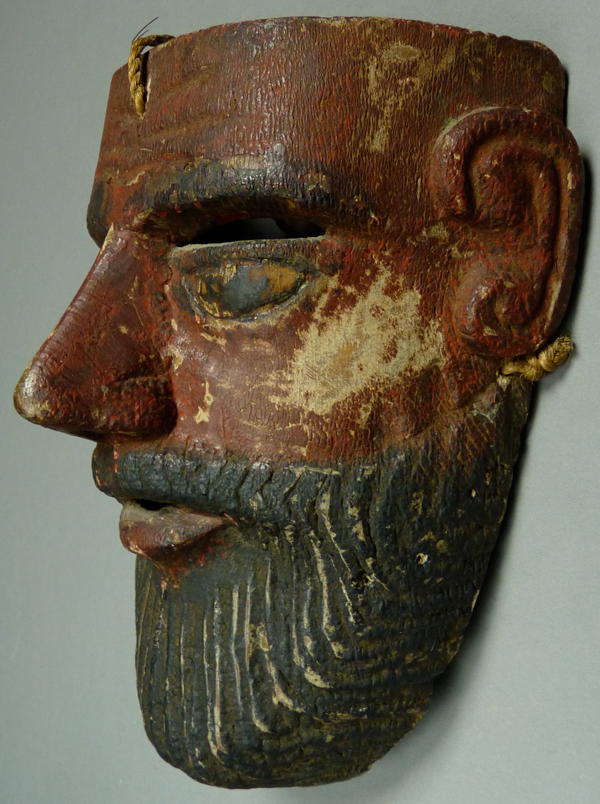

I will end with another old and elaborate mask that may have been worn by Santiago. This mask, which was found in Mecatlán, Veracruz in the 1970s, closely resembles one in Moya Rubio’s book (1986, 124, plate 151), a mask that he describes as “Antique polychrome wooden mask of St. James apostle. Dance of the Santiagos. Sierra de Puebla. Height 21.5 cms.” [8½ inches tall]. It “has all the classical qualities of the XVIII century” (135). In my view, this mask could easily be 100 years old. Unfortunately, I don’t recognize the ear design, nor did the mask come with any history beyond the year and place of collection.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 7 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The back shows extreme darkening from age and use.

Next week I will tell about the masks worn by the Pilato dancers, to complete my overview of the dance of the Santiagueros.