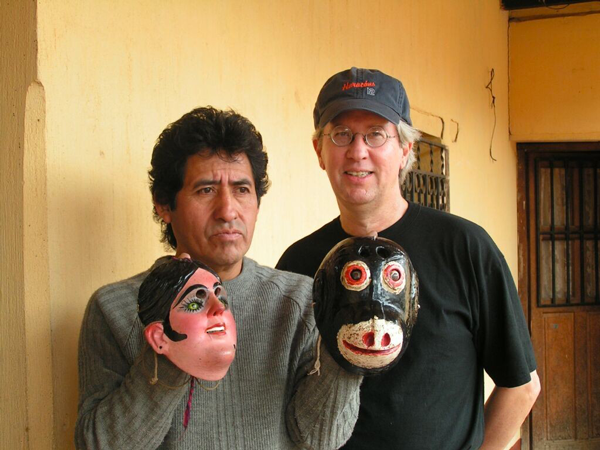

In last week’s post (July 6, 2015) I included a Monito (little monkey) mask from San Fernando Chiapas that performed with a Tigre in what appeared to be a precontact dance. The masks of Chiapas and Guatemala are closely related as I will later explain, so in today’s post we will examine Monkey masks from Guatemala that perform in a variety of dances, to initiate a series of posts over the next ten weeks about Guatemalan masks. Here is a Mico (monkey) mask from Chichicastenago that was purchased from Luis Ricardo Ignacio by my late friend and fellow collector, Gary Collison. This photo is courtesy of Gary and Linda Collison, and includes Gary, Luis Ricardo Ignacio, the Mico mask, and another mask of a woman who was the Wife of the Deer Hunter.

Luis Ricardo Ignacio is the nephew of Miguel Ignacio Calel, who was the proprieter of a well-documented morería (mask and costume rental business) in Chichicastenango; his masks were marked on the back with branded letters—MIC. The female mask in the Collison photo bears this mark, but none of the masks that follow in today’s post have morería marks. Both masks, along with others with jaguar faces, were said to have been used in La Danza del Venado, the Deer dance.

Here are additional photos of the Monkey mask from Chichicastenango, Guatemala.

The classic dance mask from Guatemala has two round vision openings above two carved or inlaid eyes; the latter are usually glass but sometimes painted nuts or wooden disks have been used instead. It is not unusual to see an old Guatemalan mask that has lost the glass eyes, leaving four openings instead of two. It is extremely rare to find a Mexican mask with this specific arrangement. Instead, what one commonly sees are paired vision openings that are directly above or directly below the painted or carved eyes.

Guatemalan Monkey masks usually have relief carved ears,but often these are hidden under many layers of paint. This mask is 8 inches in height, 7 inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

The back shows excellent wear. The lighter color on the upper corners indicates that the back of the mask was reworked (enlarged) in those areas to suit a change of wearers. The inset eyes are made from glass.

Here is a link to a dance of four Micos with a Tigre (wearing a red suit); they engage in a playful contest for food, not unlike the dance in San Fernando Chiapas. Note the elaborately embroidered suits worn by the Mico dancers; such suits are typical in Guatemalan dances. Unmasked Monkey dancers in Chamula Chiapas also wear such elaborate uniforms. The Monkey masks worn by these Micos in the video appear to be identical to our first mask. This video also demonstrates one dramatic difference between the dances in Chiapas and those in Guatemala—in Guatemala the music is often provided by a marimba rather than by a flute and drum.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WHMntrlae5o

I have five more Monkey masks to show you, but first I must provide some history.

The masks of Guatemala and those of Chiapas share some features, and these similarities are not coincidental. Although we now regard Guatemala as a separate nation from Mexico and recognize Chiapas as a Mexican state, these distinctions blur their shared history at two levels. First, these had originally been neighboring areas of a region dominated by Mayan kingdoms; they had a common culture. Then, when Spain divided its colonial empire of New Spain into a series of intendancies (administrative districts), one of these was the Intendancy of Guatemala, which combined the present areas of Chiapas and Guatemala. I have decided to include Guatemalan masks on this site due to their similarities with the masks of Chiapas and because of their shared histories.

A map from Pinkerton’s Modern Atlas, “Spanish Dominions of North America: Middle part” (originally published in London in 1812 and reprinted in Philadelphia in 1820), demonstrated these intendancies. Here are photos of the 1820 map (from my collection). The Intendancy of Guatemala lies in the lower right hand corner of the original map.

Here is an enlarged section of the map that highlights Guatemala.

Tabasco and Yucatan were independent territories to the north, while Chiapas was contained within Guatemala and had no separate identity. Chiapa [de Corzo], the major site for the Parachicos dance (see June 29, 2015 post), lay just within Guatemala at the boundary (colored green) that separated that territory from Veracruz (look to the left of the G in GUATIMALA).

Ironically, all this was rapidly changing during the period when this map was originally printed and then reprinted in an American edition. The Mexican War of Independence, which lasted from 1810 until 1812, ended Spain’s control and established the possibility for self government by these former Spanish colonies. An extended planning process followed, culminating in the acceptance of Chiapas as a prospective Mexican state on September 14, 1824 and the formal establishment of the Mexican Republic [of states] on October 4, three weeks later. With this, Chiapas was carved out of Guatemala to become one of the Mexican states and the rest of Guatemala remained as a separate nation.

Here is another Monkey mask from Guatemala. I purchased this from the Cavin Morris Gallery in NYC; it was said to be from Alta Verapaz. It is certainly different in appearance from our first example, although it does have the same layout in terms of the eyes and the vision openings. The recessed eyes of this mask are carved. In the dance of the Monos y Micos (see discussion of Joel Brown and Giorgio Rossilli’s book following this set of three photos), these pink-faced masks are the Micos.

One obvious difference is the presence of carved curls to mark the hairline and another is the carved ridge that marks the boundary between the Monkey’s pink face and the surrounding fur. One is tempted to describe this as a more realistic portrayal of a monkey, but this urge is tempered by the presence of elaborate painted designs on the brows and cheeks, not to mention the gold chin. These two masks represent two very different design styles. In Guatemalan Masks: A Second Portfolio (2011, page 49), Joel Brown shows a nearly identical mask from Alta Verapaz.

The ears are carved in relief. This mask is 8 inches in height, 5½ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

The back demonstrates evidence of heavy use.

In 2008 Joel E. Brown and Giorgio Rossilli published Masks of Guatemalen Traditional Dances (in two volumes). In my opinion this is the most comprehensive work available to date about the dance masks of Guatemala, one that any serious collector of Guatemalan masks should certainly own. There I learned that characters wearing masks with monkey faces are found in many contemporary Guatemalan dance dramas. A mask like the first in this post appears in a dance photo from San Raymundo in 2000 (Volume 1, page 145) and masks like the second mask, from the Baile Monos y Micos in Carcha, are found in Volume 2, pages 500 to 503. You can order this book and several others from Joel E. Brown, 2020 Harbourside Drive, Longboat Key, FL 34228107.

There are many other valuable books about Guatemalan masks and dances and I will highlight just a few:

Máscaras Y Morerías De Guatemala/Masks and Morerias of Guatemala, published in 1987 by Luis Luján Muñoz, was an early attempt to provide a comprehensive introduction to these masks. One can learn a lot from this book, while also noticing how much was not yet known at that time.

Guatemalan Masks: The Pieper Collection, by Jim Pieper and published in 1988, is likewise a remarkable introduction from a time when much was unclear, leading the author to puzzle and speculate as he encountered old and beautiful masks that were shrouded in mystery.

Guatemala’s Masks and Drama, published by Pieper in 2006, presents these masks in vivid color along with much more information. This definitely belongs on the collector’s bookshelf, along with the more recent Brown books.

What you will discover, if you carefully read these works by Pieper, Brown, and Rossilli is that they approach the subject of Guatemalan masks from two distinctly different perspectives. While Pieper is willing to speculate about the age and identity of ancient masks for which sure knowledge or certainty are unlikely, Brown and Rossilli prefer to avoid such speculation. Likewise Brown emphasizes the variability in mask design and use, in the face of a widespread tendency for formulaic attribution based on appearances. I have concluded that it is best to strive for a balance between these two positions.

The next mask, collected by Spencer Throckmorton in Guatemala and with no record of its intended dance, appears to be another Mico mask from el Baile de Monos y Micos. In fact it closely resembles a Mico mask (on page 502 of Brown and Rossilli’s book) that is in the collection of Señora Eva Hannstein.

This mask is very well carved. Note the bulging eyes and the carefully carved nose.

The ears are carved in relief. This mask is 7 inches in height, 5½ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

This second pink-faced Mico mask appears to be old and worn.

Next is a mask like the Mono masks in the Brown and Rossilli book from the Baile Monos y Micos; those have black faces. We see the same shape and features as the Mico mask, and with remnants of the gold paint; this was once a Mico. Obviously the eyes of this mask are more simply carved than some that you have seen earlier in this post. Spencer Throckmorton collected this mask in Coban.

The worn and otherwise imperfect paint distracts one from noticing that this is a truly elegant mask.

Probably this mask also had a pink face in the past. As usual, this Monkey has relief carved ears. It is 8 inches in height, 6 inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

This is yet another fairly old mask. The back has been scraped (I wonder why).

The next two masks, again obtained from Spencer Throckmorton, were also found in Coban and were said to have performed in the Dance of the Animals. They look like simplified versions of the Mono mask that we just viewed. Brown and Rossilli discussed the Baile Animales that they observed in Rabinal in 2000 (Volume 1, pages 207 and 208), and in two of their dance photos on page 207 one can see a “Mico” that is quite similar to the first of these Animales masks.

This mask has inset eyes.

As we have learned to expect, the ears are carved in relief. Because the layered paint has chipped away in that area, we can see that the original ear was finely carved.This mask is 7 inches in height, 5½ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The back view reveals that the inset eyes are composed of carved wooden disks. The rim of the mask is darkly stained from long use.

Here is the second mask from the Baile Animales.

This mask looks rather different from the one before because the rim of carved hair around the face is heart shaped and because the area of simulated hair is grooved.

The ears are carved in relief. This mask is 6¾ inches in height, 5 inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back of this mask is not only worn, but battered.

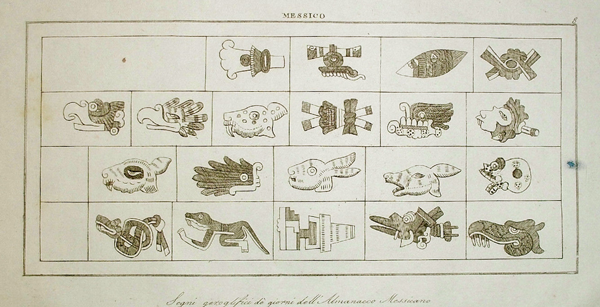

I will end this post with a highly unusual mask that I had purchased from the Cavin Morris Gallery in 1995. At that time I thought that it was the mask of a shaman. However, I now realize that this is most likely to be a mask of a monkey. One clue is the grooved hair, which is like the hair on the last mask. The second clue is the chevron shaped cheek design; I had become aware that this cheek shape might mark a monkey when I compared the Black/White Negritos in Pinotepa Nacional, Oaxaca to the traditional Aztec day sign for monkey, viewed on the right edge of the second row on this old print.

Pieper (2006, pages 93 and 123) included Guatemalan Monkey masks that have such a design framing the face.

This is an unfamiliar monkey, and I have not yet identified a town or a specific dance that has monkeys like this one.

I would like to know the significance of the relief carved designs on the cheeks. Do they represent snakes? In last week’s post I included a Tigre from Suchiapa Chiapas that had such designs flanking a Christian cross; are these Christian symbols? Although none of today’s monkeys are marked with crosses, Brown and Rossilli do show one that has a small cross painted on the forehead, in the Baile Mazate (Volume 2, pages 347 and 348) and Pieper shows another with a recessed cross (2006, page 93).

This mask is 8½ inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 2¼ inches in depth.

It has significant damage from fungus or infestation. There is also evidence of wear.

I hope that you have enjoyed seeing these Monkey masks from Guatemala. Next week I will show other masks from Guatemala, Tigre (jaguar) masks and an old Venado (deer) mask.