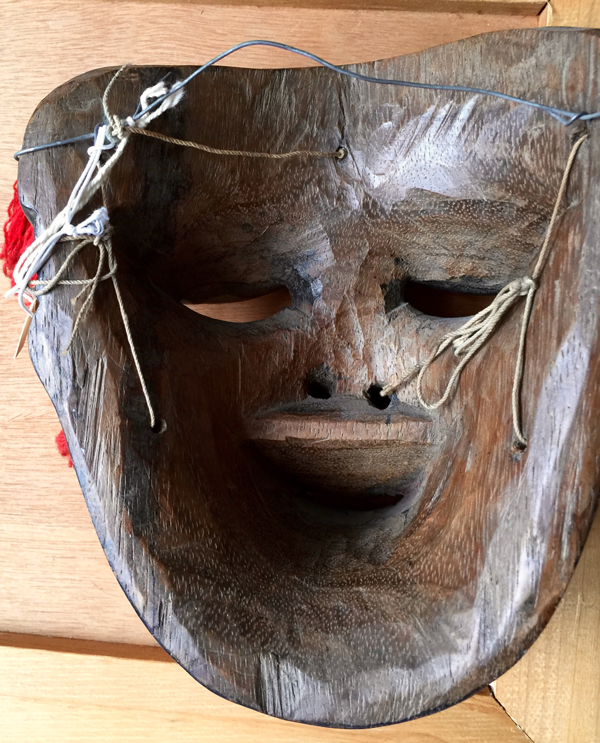

On June 1, 2015 I told of traveling to the Mixtec villages on the coast of Oaxaca to visit a family of traditional carvers. I introduced you to the masks of the late Filiberto López Ortiz. Last week I told about Filiberto’s brother Ladislao López Ortiz, another master carver in Pinotepa Nacional who is still actively carving. These discussions prompted Randell Morris to send me photos of four masks in his collection that seemed similar to those I had included. Here is the first of these masks. One is immediately impressed by the quality of the carving and the patina.

This is a Black/White Negrito mask, a near duplicate of the mask I showed last week that was carved by Ladislao López Ortiz. I call your attention to some characteristic details—the finely carved protruding eyes, the grooved whirling chevron designs on the cheeks, the finely carved nose, the stylized mouth, and the cleft chin.

From this angle one can see the complicated plains of the face, including a glimpse of the thick edge of the right eye, to the left of the red tassel.

The back of the mask is impressively smooth and worn. It is sufficiently beautiful to make me think of similar masks by Ladislao’s brother Filiberto, a man who demonstrated an extremely sculptural approach to the carving of the backs of his masks. It is carved from guanacaste wood and this has taken on a beautiful color after years of use.

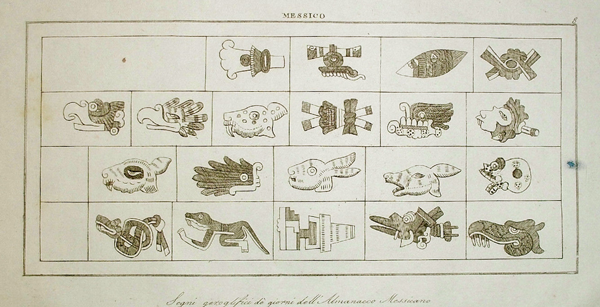

The tag says “monkey character;” I have never previously heard this mask described as having the face of a monkey. However when I looked at drawings of the traditional day signs that were used by the Aztec and Mixtec Indians, wondering if any of these masks resembled the day sign faces, I was surprised to notice that the face of the Monkey day sign (second row at right) is framed by the same shape as the white scrolled area of this mask. This will bear further research.

This plate was originally published in Italy in 1834 by A. F. Falconetti. At bottom right we see the crocodile sign and adjacent to that one is the sign with Ehecatl’s face, which represents “wind.” The toothy symbol in the top row is dzahui, the Mixtec sign for rain. The spotted animal with fangs in the second row represents the jaguar.

A second view, without the tags and strings, confirms that the back design is that of Ladislao. It is indeed very nicely carved.

What follows is the photo of the back of a Black/White Negrito by Ladislao López Ortiz from my collection that you saw in last week’s post, for comparison.

This seems a good place for me to show a Black/White Negrito mask from my collection that is characteristic of Filiberto Lopez Ortiz’s style. You will see that there are only subtle differences; at first glance the two masks seem nearly identical. The comparison is slightly hampered by the fact that the tip of the nose was broken off long ago on this mask.

It is immediately obvious that the eyes have the same delicate carving. Yet they differ, as those of Ladislao are carved as if elevated on a rim whereas Filiberto’s eyes are thin, more like poker chips than checkers. This is a subtle difference in the design, yet there is really no difference in the artistry. Likewise Ladislao chose to carve the chin as if fully cleft, while Filiberto carved a chin that was partially cleft, a delicate difference. It was such delicacy that brought Filiberto so much attention!

In recent years Ladislao has changed over to this partial chin cleft style, but in his hands this feature is still not as delicate as on the example by Filiberto.

It might seem that these differences reflect two masters demonstrating their individuality. This may be so, but the explanation is actually more complicated. Both Filiberto and Ladislao were trained to carve by their grandfather. Much later, after Filiberto’s death, Ladislao gained access to a family collection of masks by their great grandfather, “el padre de mi abuela.” Those were masks that neither of the brothers had previously seen and that were different in some details from those of their grandfather. In this context Filiberto worked from his grandfather’s model, which he refined, while Ladislao was ultimately able to elaborate on the style of his great grandfather as well. My collection of masks by Ladislao includes several interesting masks that are obviously based on those of his great grandfather. The big picture is that the Black/White Negritos and the all black Negrito masks carved by these two brothers are ultimately refinements of masks that were already being carved by their great grandfather. We have no idea how much older these designs might be.

This side view illustrates other differences between the styles of the two brothers—Filiberto has used a more slender chevron on the cheek and the tip of the chevron turns to follow a circular line, while Ladislao’s levels off. Also the base of the extended mouth has been carved more precisely. Look at the counterpoint between the rectangular base of the projecting mouth and the curving folds of the cheek. One rarely sees this level of elegance in a Mexican mask.

Usually the backs of Filiberto’s masks are also more elegantly carved than those of Ladislao, not because Ladislao is incapable of carving more finely, but because he often failed to make it a point to do so; he carved the backs of his masks to the normal standard for his community. Filiberto, on the other hand, became so fascinated by sculptural perfection that he carried this aesthetic to every aspect of his masks. I bought this remarkable mask in 1988.

I have subjected you to such a detailed comparison to make this point. Filiberto’s exquisitely artistic style caused him to become famous in Mexico, and one imagines that his fame would have spread even further if he had not been murdered at a young age. In contrast, his brother Ladislao was and remains an equally talented carver, but because he is apparently less driven and his sense of design is slightly different, he has never received much notice outside of his immediate community. On the other hand, if one observes a video of dances in Pinotepa Nacional, such as the one at the end of last week’s post, his masks are everywhere! In summary, from the perspective of North American collectors Ladislao has long been hidden in his dead brother’s shadow, despite the fact that he is such a wonderful carver. Further evidence of this will soon follow.

I had met Randell and his wife, Shari Cavin, the owners of today’s mystery masks, in 1994. Then, as now, they sold art in New York City at the Cavin-Morris Gallery, featuring “works of international self taught artists” and “arts of the ethnosphere …” (essentially outsider art, folk art, and beyond). This Spring they celebrated the 30th anniversary of this adventure, displaying many dazzling objects that reflected their experience over that period of time. Here is a link to that recent exhibition. I call your attention to a polychrome swordfish! You may notice a mask or two; in the past there were many exciting masks, and for all I know they still fill a corner of the gallery storeroom. On these pages you have been shown masks in my collection that came from the Cavin-Morris gallery, such as a mask of the soul (Alma Petoicha) on September 22, 2014, and you will definitely see others in future posts.

http://www.cavinmorris.com/blog/2015/3/3/in-dreams-begin-responsibilities-30-years-at-cavin-morris

Here is another of the Cavin-Morris masks, one of the all black Negritos from Pinotepa Nacional. It too has design details that are characteristic of the hand of Ladislao López Ortiz. Resist it if you can.

This is really a glorious mask; it is dramatic, worn, and very well carved. The proportions of the nose and teeth tell us that this was carved by Ladislao. You saw three essentially identical masks in last weeks post, but the patina on this mask adds to its majesty.

Look carefully at this back. Ladislao has carved it to a normal standard and then significant use has polished the guanacaste wood to a beautiful color. We see the usual shelf under the hollow for the dancer’s nose, and below that the cone shaped air passage. One must scroll back to the front view to see that this passage extends to open under the teeth. Were this an all black Negrito mask by Filiberto, then there would be no shelf; the air passage would be rendered as a smooth bowl that flowed smoothly into the hollow for the dancer’s nose. Then again, as I showed you in earlier photos today of the Black/White Negrito masks, in the absence of the air passage both Filiberto and Ladislao carve a full shelf under the hollow for the nose.

The next two masks were purchased by Randell from Robert Lauter, a well known folk art dealer and collector in California. I am less certain about the respective identities of the carvers. The overall appearance of the next mask may remind us of the masks of Ladislao and Filiberto, but repainting in the course of use has obscured the details of the face. See for yourself.

This mask is certainly in the style of Pinotepa Nacional, it is apparently well carved, but the details are difficult to see. The beautiful handmade tassels are multicolored—purple, pink, yellow, and red.

When in doubt, one can look to the back of a mask for further clues. What do we see? This is NOT a mask by either Filiberto or Ladislao López Ortiz. It is the work of another carver, perhaps the pupil of Filiberto, José “Che” Luna from the town of Santa María Huazolotitlan, now an elder master carver himself. If you recall last week’s post, I demonstrated that both Filiberto and Ladislao made it a point to honor the memory of their grandfather by keeping alive his innovation—a carved tube that channeled fresh air to the dancer’s mouth. This mask lacks that feature. There are large carved nostrils along with a small bored hole at mouth level, visible just below the leather thong, instead of a carved tube that opens under the upper teeth.

Pause a moment to notice the craftsmanship of this metal stand. The thin tubing has been bent to conform to the shape of the back of the mask and the end bent to fit into the hole in the middle of the forehead. On the lower left (at about 8 o:clock) a tiny bolt on a threaded base is aligned with another hole in the mask; turning the bolt into its threaded mounting extends it into the wooden passage, locking the mask in place on the stand.

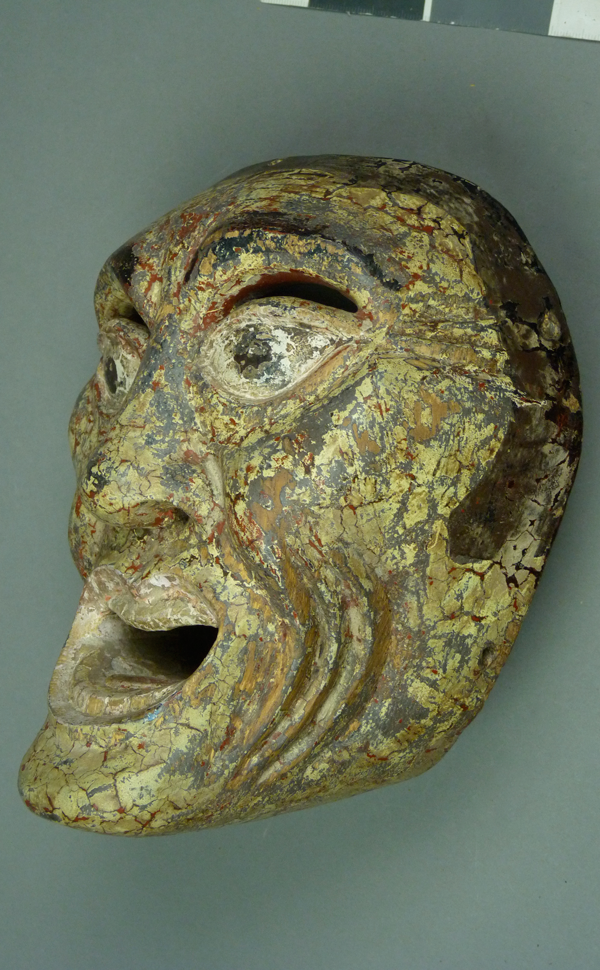

The last of the Cavin-Morris masks is quite different from the other three, so different at first glance that one is forced to consider other carvers. The paint is particularly strange, but not unlike that of the previous mask.

This mask is in the style of Pinotepa Nacional, it is a masterpiece of dynamic design, and yet it looks nothing like the other three masks. For example, note the broad nose with its flowing lines; it reminds me of a manta ray swimming. The slits for vision are carved under the eyes instead of above them.

The broad flowing upper lip is also impressive.

Again we can turn to the back for further assistance. What do we see?

To my surprise, I see two things that I didn’t expect—the breathing tube that was invented by the grandfather of Filiberto and Ladislao and the perfectly carved back that is characteristic of Filiberto López Ortez. This could be an unusual mask by Filiberto.

This photo provides a clearer picture of the bolt mechanism that locks the mask onto its stand. Two prongs on the left arm are firmly held in holes that were intended to anchor strings or straps. The thumbscrew on the right allows “no tools installation.”

I have a similarly unusual mask in my collection, which I bought in Santa Fe in the 1990s. It has more or less the same strange paint, the face has yet another unusual and very well carved design, but the back is less perfect. I have to admit that my example remains mysterious and anonymous despite its artistry. While I can’t imagine that it was carved by anyone else but Filiberto, the details don’t clearly support that attribution. Some wonderful masks must simply remain unclaimed. Here is my mystery mask.

The wrinkles around the corner of the mouth and others extending laterally from the left eye certainly make me think of the López Ortiz style, while the eyes look just like the eyes on Filiberto’s masks. The nose is rather restrained, suggesting that this is not a mask of a Negrito. Indeed, despite the painted on sideburns, I perceive this as the mask of a Caucasian woman. Given the expressive open mouth, I imagine that this mask was worn by one of the outrageously behaving female dance characters found in a neighboring town, Pinotepa de Don Luis. During Carnaval (carnival) these “women” join with equally rough looking Caucasian Viejos (actually carousers would be more accurate), pretending to demonstrate shocking promiscuity and intoxication. These couples are obviously demonstrating “what not to do.” The generic name for such dancers in Mexican dances is Feos (uglies, perpetrators of ugly and inappropriate behavior) and such a female character is a Fea.

The back of this mask is particularly odd and gives me pause. It is well carved, but it does not make me think of either Filiberto or Ladislao.

I showed photos of this mask to Che Luna, whom I suspected of being the carver. He neither claimed it nor attributed it to anyone else. Who else is there? Well, actually there is a third brother about whom we know little. He carved in the past. Currently he is unavailable, living and working in a distant city. Barbara Cleaver and I hope to learn more about this brother and his work.

Next week I will show some different masks by Ladislao López Ortiz, mainly masks of Tigres (jaguars), plus one skull.