This is the third post in a four part series that explores and attempts to clarify the boundary between authentic Mexican dance masks and other invented (or “decorative”) masks that pretend to be authentic. This boundary had become dramatically blurred after the publication of Donald Cordry’s book, Mexican Masks, in 1980.

In last week’s post, I explained the mixed nature of Donald Cordry’s book, noting that it has so much to teach us, because it is filled with excellent examples of the real, the false and the ambiguous. I emphasized that the dance photos and the photos of carvers with their work provided valuable information, and I gave examples. This week I will discuss the authentic traditional masks in this book and next week I will survey the decorative masks.

I should begin with a caution. Because the traditional masks in Mexican Masks are so good, they will generate a long list, but one that would be dry and boring in the absence of any illustrations. I lack permission to reproduce the actual photos from the book, and I doubt that all of my readers will already own Cordry’s book, so my solution is to introduce similar or related photos of masks from my collection or from the collections of others. I could simply include a few photos to whet your interest, but because the topic is so rich and important, I have decided to present many photos in order to properly celebrate the positive elements of this collection. It is unlikely that my future posts will have anywhere near the number of photos that you will find in this one. I have gone to such lengths with the greatest pleasure.

Here is my list of the authentic traditional dance masks in Cordry. It is likely that I will miscall a mask or two, or omit an ambiguous mask that is actually authentic, particularly since we are working from photos rather than handling the masks directly, so I apologize in advance for any inadvertent errors. I am certain that the reason no one has attempted this feat in the 34 years since Mexican Masks was published is due to the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty associated with the task. As I noted in last week’s post, I do have the benefit of having reviewed the contents of Mexican Masks with the late Jaled Muyaes, a well known and highly knowledgeable Mexican collector:

Plate 2 (page viii), a Rastrero of leather and fur. Jaled Muyaes did not question the authenticity of this mask. I do not presume to know if it is authentic, but I like the simplicity of the design features.

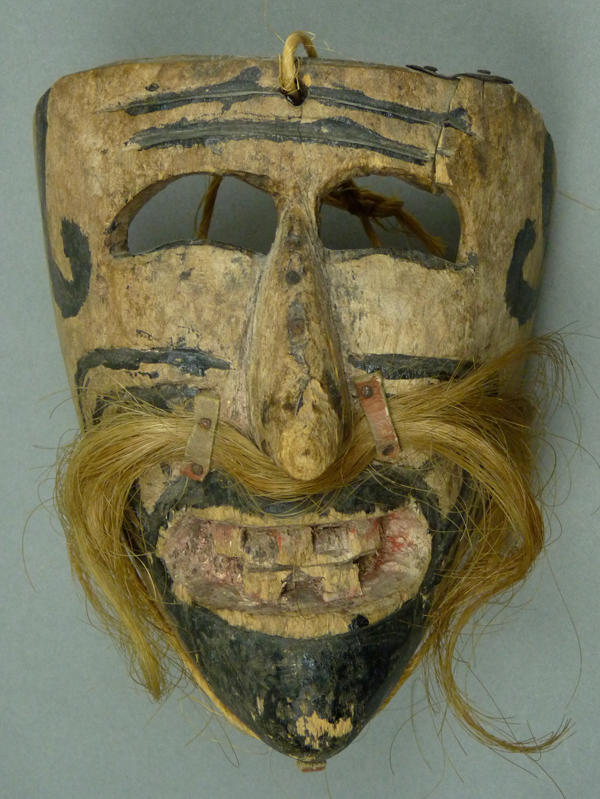

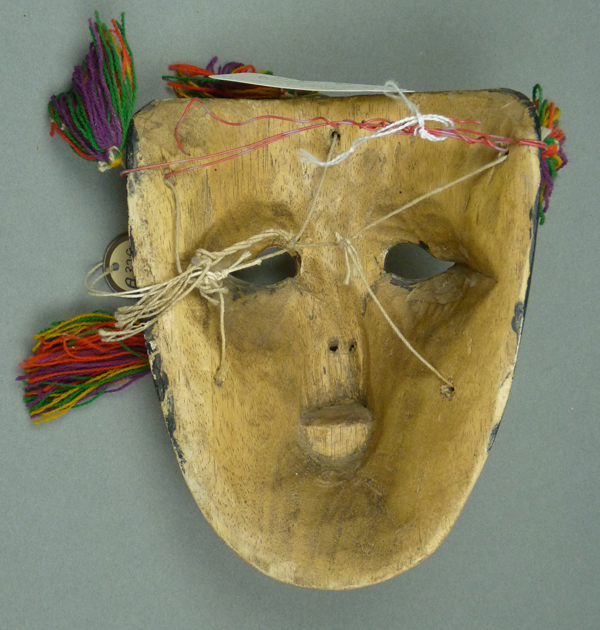

Plate 3 (page 2)- two excellent Corcovi masks from Michoacan. The one on the left appears to be much older, that on the right was carved by Victoriano Salgado Morales, of Uruapan, Michoacán. Here are photos of a Corcovi mask from my collection, carved by Victoriano.

A Corcovi mask by Victoriano. I bought this on EBay, in 2010.

The back of the Corcovi mask. The back was apparently treated with a protective finish, so that wear is demonstrated by wearing away of that finish, rather than by darkening of raw wood. One commonly finds such finished backs on the masks from Michoacan.

Plates 4 and 5 (4), 118 and 119 (84), 124, 125, and 126 (87), 127 (88), 128 (89), 203 (160), 204 (162) are authentic prehistoric masks.

Plate 6 (page 5)- I must confess, I thought that this was decorative. Jaled did not; here is his notation for this mask—”Zumpango del Rio, [Guerrero] Diablos.” Here is a link for recent dance photos from the same area. http://muertequerida.com/maizo/?p=1214

Plates 8 (page 7)- two very unusual masks, probably by the same hand (note mouth design and painting style), and possibly the earliest documented decoratives. However, Jaled Muyaes did not question these masks, which were in the collection of a famous Mexican artist and author.

Plate 11 (8). #11 is difficult to see, due to tattered scraps of cotton or fur; it is probably a Moor, and the holes across the forehead were necessary to bind on a headdress or a tin crown.

Plate 12 (8) may be a Rastrero (tracker) from the dance of the Tlacololeros (farmers of corn who become jaguar hunters to create safe working conditions). Here is a photo of an ambiguous mask from Charles Thurow’s collection that was included in Celebration of Masks as unidentified (Plate 138, page 28). This is also likely to be a Rastrero mask, or perhaps a clown.

Note the old repair on the top and the excellent patina on the back.

Plates 13 (9). #13 is seriously damaged, yet has very distinctive features, such as the stylized chin. If one studied many masks, the identity of this one would probably emerge, despite its damaged state.

#14 (9) is a classic animal devil, with twisted snakes over the eyes. One sees similar masks from the Mexican states of Guanajuato and Michoacán. Here is an example from my collection, from Michoacan. Such diablos dance in the Pastorela, the Shepherd’s Play.

The back of the Pastorela Diablo mask. Note the cloth that was glued along the edge of the back to cushion the face of the dancer.

Plate 19 (16)-a spectacular old mask of a woman, well documented, worn, and with old repairs. It is rare to see such a noble old mask. Here I will include a more recent example. A dancer painted a name on this mask—”Vieja La Roqueta” (“Rocket Woman?”), from Guerrero. This mask has a beautiful face, but its appearance is obscured by later painted additions.

This is another mask where the back was stained or painted and the smoothing or polishing of the finish is the indicator of wear.

Plate 29 (26)- a remarkable group of masks. The three at the top are of molded leather, while the rest are carved from wood. They are well described in the caption, and similar masks are shown in action on Plate 33 (28). Mask 29d can also be seen in Celebration of Masks (Plate 43, page 17), loaned by Charles Thurow. Here I will include a pair of these (wooden) Catrine masks from my collection. They have doll’s eyes with eyelashes and movable lids that were imported from Germany. They probably were made in the 1930s or 40s.

One pulls the string to lower the eyelids.

Plate 34 (29)-Jaled Muyaes and I both thought that this Diablo mask was authentic.

Plate 35 (30)- another Diablo mask that is primitive but authentic. It has lost its horns, but still has other typical diablo features—relief carved snakes, and fangs.

Plate 36 (30)- it is large at 11″ in height and essentially a clown that would be very effective in action.

Plate 39 (page 35)- an unusual Diablo mask. As Cordry noted, one can see a similar mask in Plate 142 (page 101), a photo of a boy tending his father’s wares, that we visited last week.

Plates 42 (page 37)- The Moro Chino masks in Plate 42 are very tall, at 15″, and the dancer peers out through the open mouth. In contrast, here is a diminutive Moro Chino mask from Guerrero that is from my collection.

Plate 43 (37) is an unusually small mask of a Moor; another example can be seen in Moya Rubio (1986, page 102). My late friend, Gary Collison, also had one of these small Moor masks in his collection. This mask is currently in the collection of the Lee R. Glatfelter Library, on the York Campus of Pennsylvania State university, in York Pennsylvania. Here is a photo of the mask from the Collison collection.

Plate 44 (page 38)- these masks of Malinche have applied lizards on their cheeks, and sisal wigs. I doubted them but Jaled said that they were authentic.

Plate 47 (40)-Several of these skull masks are suspect, but the one on the upper left—47a according to Cordry’s system—is probably very good, having been collected in the field by the Cordrys in 1931. Alfonso Caso included it in his catalogue of the Máscaras Mexicanas exhibition of 1945. The mask on the lower left, of copper, is certainly decorative, as are the skulls with double faces. I am uncertain about the rest.

Plate 48 (40), Plate 59 (47),and Plate 151 (106), taken as a group, are highly important. Filiberto López Ortiz, who was the grandson and student of a circa 1900 Mixtec master carver from Pinotepa Nacional, Oaxaca, emerged in the mid 20th century as one of THE great Mexican mask carvers. His masks have a level of artistry that is extreme. The mask in Plate 48 is terrific, but the most superb of these masks is the Negrito at the very top pf Plate 59; the rest of the masks in that plate come close behind. I will devote a post to this carver in the future. My present point is simply this—with the exception of some small photos by Ruth Lechuga, of which only one is identified by name, Cordry’s is the only published book that has any photos of Filiberto, or of his masks. Here are photos of a Negrito mask by Filibeto from my collection.

The backs of the best masks by Filiberto López Ortiz are remarkably carved to a state of near perfection.

Here is another mask by Filiberto López Ortiz, this one a Cuanebuela from the Tejorones dance (collection of Charles Thurow). Cordry did not show one of these masks in his superb group. The Cuanebuelas, the owners of the ranch where the Negritos work as farmhands, dance with the Negritos (the characters who wear the black and white mask just above).

The face of this Cuanebuela is very finely carved and painted.

As with the previous mask this one has a carefully carved back.

Plate 49 (41)- Jaled Muyaes was of the opinion that these masks of Christ and the Virgin of Guadalupe were genuine. Seen only in the front view, they look good.

Plates 52 and 53 (44) and Plate 54 (45) are all beautiful masks from the Tejorones dance, found in coastal Mixtec villages in Oaxaca. The masks of Filiberto López Ortiz are also from the same dance. Here is a typical Tejorone mask with the appropriate headdress, made from rooster feathers.

These small masks look comical when worn by an adult whose head is wrapped in a bandana, as the dancer has the appearance of a person with a very small face.

Plate 55 (45) this appears to be an authentic and heavily used example of the leather Tigre (jaguar) masks used in Zitlala, Guerrero. However, note that many of these have been made for tourists in recent years. I like these masks, yet I don’t own one, because I perceive them as so difficult to evaluate. Plate 184 (135) shows a leather worker making such a mask. Here is an example of one of these masks from the collection of Charles Thurow.

Plate 61 (48) appears to be an excellent old Diablo mask that has lost its horns.

Plates 62 and 63 (49) contain excellent Parachico masks. They are accurately described in the captions. Here is a Parachico mask, with sisal headdress, from my collection.

This is an old Parachico mask with remarkable patina.

Plate 64 (50) and Plate 91 (69) are great old masks from the Cinco de Mayo drama.

Plate 65 (51), an undocumented bearded man with a white face that is unusual and interesting; Jaled Muyaes considered it to be authentic.

Plate 66 (51) these Azteca masks are strange in appearance, but they are authentic and interesting. However, Cordry’s description of these masks misses the mark. The concept of these is that the mask simultaneously provides the dancer with a face and a real or potential adversary. Often one sees the face of an Indian Chief, nose to nose with the face on the mask. On these examples in Cordry’s book, perhaps the adversary is a nation or region, depicted by a map. These masks are obviously humorous because the mask’s tongue engages the “enemy.” Here is an Azteca mask from my collection.

The initial “R” on the back of this mask may refer to either the carver or the dancer.

Plate 69 (54) appears to be an excellent mask of an old man. It is attributed by Cordry to the dance of the Viejitos, in Michoacan, although it could be a Hermitaño from the Pastorela.

Plate 70 (54) Cordry describes these as “Devil masks.” This is incorrect, but the masks are authentic and remarkable. These are Tastoane masks, from the dance of the Tastoanes. The Tastoanes represent barbarians, outsider figures who misbehave. They behave in a manner that ordinary citizens might like to behave, but dare not, due to potential negative consequences. By staging dance dramas where these inappropriate actions are projected onto outsiders, the architects of the dance create the opportunity for a subversive theatrical performance. The Tastoanes dance, which I explained at length in my book, is found in the Mexican states of Jalisco and Zacatecas. There is considerable variety in the masks used for this dance; they can be entirely made of leather, as in this case, or of leather with wooden and plaster features, or entirely of wood. In a future post I will focus on the Tastoane masks. When I discuss Plate 163 (18), I will show a Tastoane mask from my collection.

Plates 71 (55), 75 and 76 (58) these are traditional Yaqui Chapayeka masks, made of leather or goat hide, with applied features of leather or wood. The Chapayekas participate in a passion play, during the Lenten season. They pretend to hunt down and crucify Christ, they attempt to overthrow the Christians in their community, and they are defeated by holiness. Their masks are publicly burned, due to the belief that they have collected the evil that has accumulated in a community in the past year. The Yaquis consider it taboo to preserve or collect such masks. The Mayo Indians have similar masks, but they are less strict in their insistence that such masks should be burned.

Plates 72 and 73 (56 an 57) These are absolutely wonderful Mayo Pascola masks that were collected by Cordry in Sonora, Mexico. Although 72b appears to be authentic, decorative Pascola masks have been made in Guerrero in imitation of this mask. I included a nice old Mayo Pascola mask in my last post.

Plate 74 (58) these are excellent Yaqui Pascola masks. I am writing a book about those masks. Here is one from my collection that once had oval mirrors on the cheeks, although these mirrors have been lost.

Plate 77 (59) a Mayo version of the Chapayeka masks, called a Chapakoba mask by the Mayo Indians. Here is an example from the Collison collection. The dancer looks out through the openings that are covered with window screen. Also see Griffith’s chapter in Behind the Mask for further examples.

Plates 79 and 81 (61) are excellent Jaguar masks from Guerrero. According to Jaled Muyaes, #80 is probably a decorative mask. I am less certain, but note that although the mask has a simple, traditional form, the eyes are painted in an elaborate fashion that one associates with the decoratives. Here is a beautiful Tigre (or jaguar) mask from the collection of Charles Thurow. It is from Tlaliztaquilla, Guerrero, and appears in the Tecuanes dance.

I really like this mask. Note the small round mirrors that serve as the Jaguar’s eyes.

The back demonstrates excellent wear.

Plate 87 (65) with the exception of 87b, which is a “whistler” from the Hortelaños dance, these are all typical and authentic Diablo masks for the Pastorela dance, in Michoacán. Here is a Diablo with a green snake, possibly by the same hand as the one in the center of the Cordry photo.

Plate 88 (66) is an authentic Diablo mask that is made of cardboard, ornamented with deer horns, and danced by Afromestizos on the coast of Oaxaca. At the end of the dance it was traditional for the dancers to submerge their masks in the ocean, leading them to disintegrate, but in recent years folk art dealers have purchased the masks at the end of the dance.

Plate 89 (66) although I had always believed that these wooden masks from the Huave area of coastal Oaxaca were invented, I read somewhere that some may have been traditionally used, and Jaled Muyaes expressed uncertainty about their status. Let the buyer beware.

Plate 90 (67) this rump mask of a serpent is probably authentic. You can see a rump mask of a giant serpent from Suchiapa Chiapas, in Esser’s Behind the Mask… (307, 310).

Plates 94 and 95 (70) are excellent traditional masks from the Mexican state of Chiapas—a rump mask in the form of a pig’s head and a bull from Suchiapa, Chiapas. Here are photos of such a bull.

The bull has a sisal headdress.

Note the excellent patina on the back of this bull mask.

Plate 97 (71), which Cordry was told came from Chiapas. Jaled Muyaes was of the opinion that it was from the Mexican state of Tabasco, where he thought it was danced in the Baila Viejo. A rare reference for this dance is El Lujo Del Sol, by Julieta Campos, published in 1988. The mask photos in the Campos book do not resemble this fine old mask, and so I am inclined to go with Cordry’s informant. The major problem here is that such masks as the one in Plate 97 and the ones in the Campos book are all very rare and wonderful.

Plate 98 (72) the baroque nature of these very rare Centurion helmet masks causes me to doubt their authenticity, but there are definitely collectors who believe that these are very old, and straight. Jaled Muyaes simply acknowledged that he didn’t know.

Plate 102 (74) this unusual and charming old Negrito mask with a lizard and a frog or horned lizard on its cheeks is probably authentic.

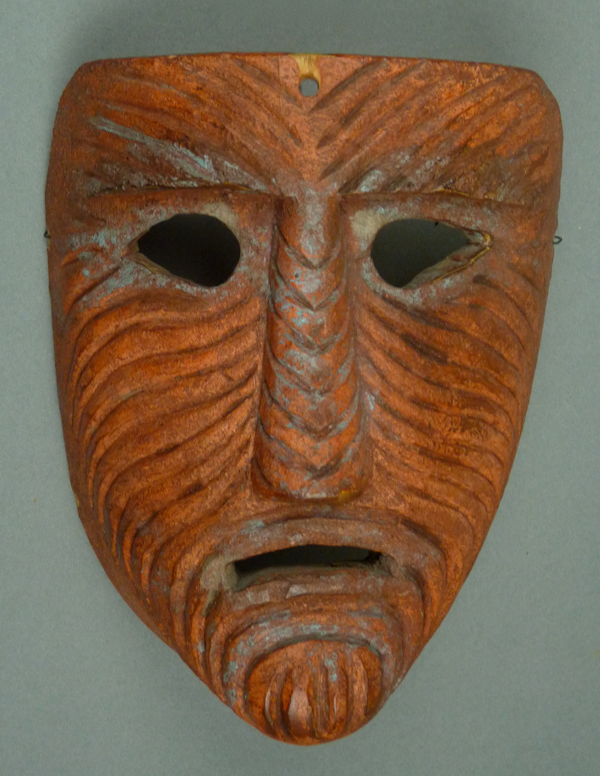

Plate 103 (75) this is a Carnival Moor mask from Veracruz. Here is another, from my collection.

Plate 104 (75) these Macho Cabrillo (billy goat) masks are used by the Otomí Indians, in Hidalgo. In fact, they wear them in the role of Voladores, flyers who spiral down on ropes from a tall pole. I wrote about this in my book. With their twisted noses, grooved faces, and stylized vision slits, these are exciting masks. I showed you one from my collection in my post of August 4, contrasting this to a decorative goat mask. Here is another that I bought in 1988 from the Cleavers.

Plate 106 (77) a devil mask that is said to be from Guerrero, although it looks like an authentic Diablo mask from Michoacan or Guanajuato. However the staff and costume are strange, and doubtful, so this may be decorative.

Plates 146 (104)- #146 appears to be a terrific mask. Other masks from Juxtlahuaca are shown in Behind the Mask in Mexico (Esser 1988, 244-261), but not this character.

The mask in Plate 148 (104) might be thought of as Cordry’s “smoking gun,” the evidence at the crime scene that explains everything. As the caption explains, the Cordrys had the exciting experience of finding a very old mask that had been preserved due to the reverence of the heirs of its original owner. One could easily believe that it was already more than 100 years old in 1940, and perhaps far older. This experience led Cordry to look for other masks with similar histories. The individuals who supplied Cordry with decorative masks probably played on this theme.

Plates 152 (107), from Tancanhuitz, San Luis Potosí, is 30 cm tall (11-12 inches), a typical height for the oversized Judio masks that dance there during Semana Santa (Holy Week), in a local version of the Passion Play. Led by an effigy of Judas, along with a dancer wearing the mask of Satan, Judio characters personify evil dead souls. Since they represent the dead, Judio dancers can wear masks of any imaginable face, including clowns, drunkards, kings, queens, professors, bishops, skulls, fallen women, and animals. This is a dance of the Pamé Indians, however they dance in a culture area that is called the Huasteca, the former land of the Huastec Indians. You can see dance photos of the Judios in a remarkable book—Lo Efímero y Eterno: Del Arte Popular Mexicano, Volume II (1971, pages 576-577). This book was also published in English—The Ephemeral and Eternal in Mexican Folk Art. Either version is rare and expensive, but well worth having. Masks and Dances are in Volume II (Tomo II), textiles and pottery in Volume I. The mask in Plate 175 (127) is also a Judio mask. Here is a Judio mask from my collection—a black skull.

Plate 153 (107) appears to be authentic. The Matachines dance is performed over a large part of Mexico, named as such or under some other name, and either with or without masks. There is not one typical Matachines mask style. To either enhance or reduce your confusion, I warn you that the Tejoneros dancers in the Sierra de Puebla can also be called Huehues or Matlachines. Matlachines is NOT a synonym for Matachines. Likewise, in a later post I will write about the Danza del Matarachín; Matarachín is NOT a synonym for Matachine either. It is unusual for Mexican mask names to be this confusing. Here is a Matachines mask from Zacatecas, from the collection of Charles Thurow.

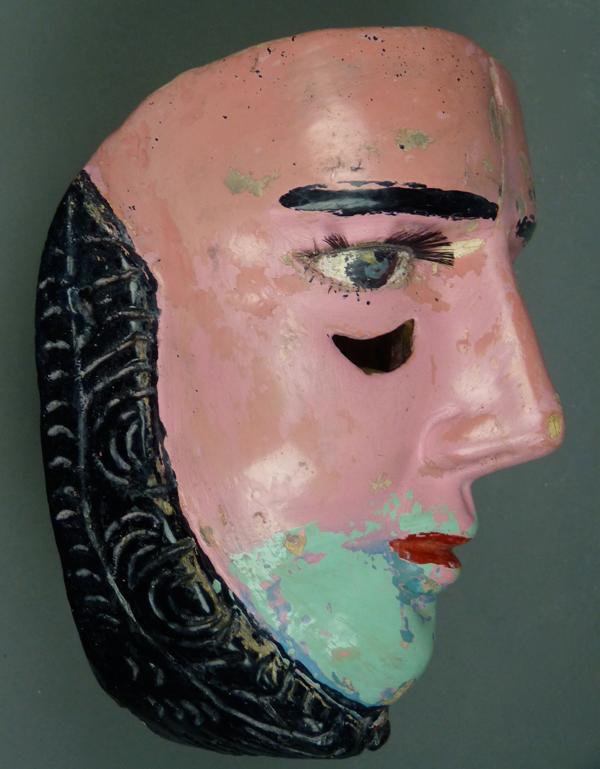

Plate 155a (112) this plate shows two authentic and wonderful masks. In fact, the one on the left is spectacular and rare. This is Luzbel (Lucifer), described in legend as the most beautiful of all the angels before he challenged God and was thrown into the fires of Hell. Luzbel was his name, prior to his fall from grace; afterward he became Satan. When you see a mask with such a handsome face, you should always think about the possibility that it represents Luzbel. This Luzbel mask comes from Guanajuato, where it was not uncommon, in the mid 20th century, to provide Luzbel with a tin crown or headdress, complete with a battery powered light bulb, m/l a transplanted bicycle light. The example that follows, from my collection, has a mirror and above this a tin flower. There is evidence of a lost decorative element below the mirror, which was held by two tin clips that remain.

The headdress on this Luzbel mask was hand made by a talented tinsmith. Paint and rust obscure the details on the front, but one can see lines on the back that were inscribed by the pointed tip of a wrought iron rod.

Plate 155b (112)- the second mask in this photo is an Hermitaño (er-mi-tan-yo, a Christian hermit) from the Pastorela dance (see last week’s post). He is frequently played as a comic character in that dance, a wise-cracking friar. This explains the ridiculously over-sized rosary beads and cross that were worn with this mask, a caricature of an ordinary rosary. We can imagine this character ostentatiously counting his beads aloud, to calm himself in the presence of the devils. Here is an Hermitaño mask from Michoacan, with a sisal braid.

Plate 159 (115) I knew nothing about this mask carved from stone, but Jaled Muyaes told me that it is worn in the dance of “Don Cheto”, described in the caption. Rare and unusual.

Plate 160 (115) Cordry presents this mask as being from the Tastoanes dance, but he also states that it came from Michoacán. The Tastoanes dance is found in the Mexican states of Jalisco and Zacatecas, while it is the Viejitos (the “Little Old Men”) in Michoacán who sometimes wear masks of clay, although more commonly they wear wooden masks. This confusion reflects the fact that there are also clay Tastoane masks in Jalisco. In my opinion, this is a Viejito mask.

Plate 161 (116) and Plate 162 (118) Leather masks, most of which are probably traditional. The style of painting on the mask at lower right (116L) reminds me of the paint on many decorative masks, and I doubt that it is authentic. I am also suspicious of B and C in the middle of the top row; note that Cordry has nothing to say about either one. I really like the two masks with their mold, in #162. Here is an old and clearly authentic leather mask that was constructed of recycled materials, and it keeps its shape from a wire frame that was probably added after collection. I got this mask from Jaled Muyaes in 2005. It was used in the Tecuanes dance in Guerrero. This mask has a number on the back that indicates it was in the Mexico City mask show of 1980.

The number on the back, 1168 above the vision slits, is difficult to see in this photo.

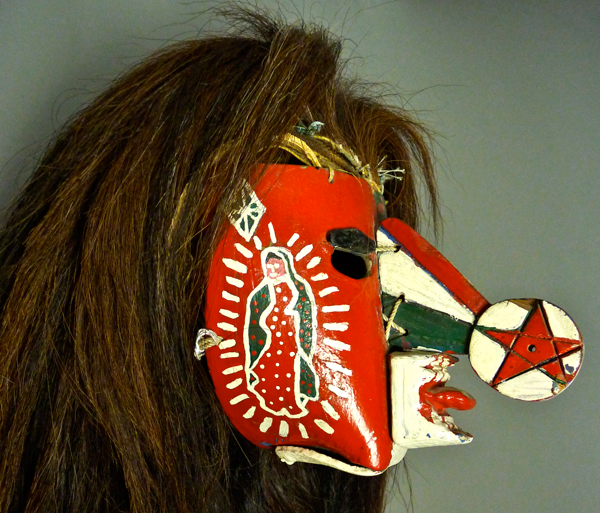

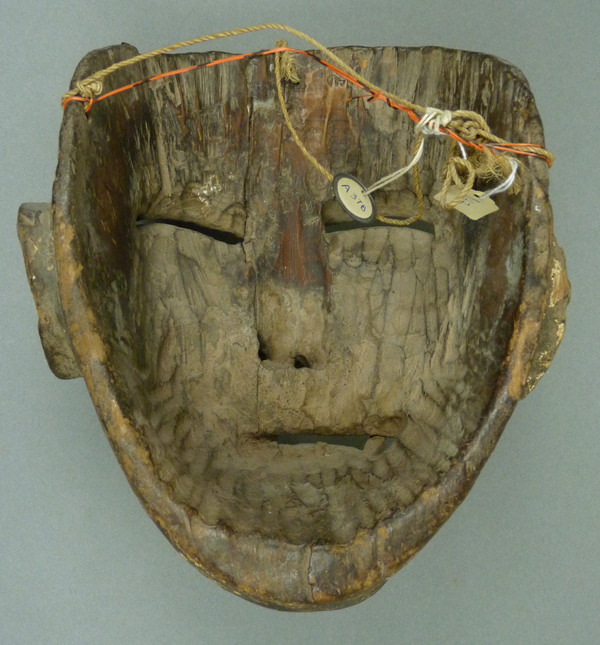

Plate 163 (118) is a good Tastoanes mask of the type with a leather base that has been augmented with applied wooden and plaster features. The hair is sisal (ixtle). Some Tastoanes masks are made of wood, and they may have horns. The Tastoanes represent renegade outsiders who challenge the status quo, in order to express Indian concerns indirectly. Here is a Tastoane mask from San Juan Ocotán, Jalisco, with hair made from horsetail. This “barbarian” has the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe painted on his right cheek, and the Virgin of Zapopán on the left (what is the mask maker tying to tell me?); most of these masks do not have painted saints, but sinister or comic images. I got this mask from Jaled Muyaes in 1997.

Plates 164 and 165 (119) these are authentic gourd masks, as described in the captions. In passing, one had been owned by Raúl Kamfer, a famous Mexican collector and folk art dealer.

Plates 166, 167, and 168 (121) authentic masks made by molding wax over a cloth core, shaped by a plaster form.

Plates 169 and 170 King and Queen masks from the dance of the Jardineros, also made of wax. They have tin crowns. Here is a pair—a King and a Queen—from my collection, formerly from the collection of Gary Collison.

The wax has been applied over a core layer of cloth.

Plate 171 (123) these masks are made from layers of cloth that are glued together over a mold. They are only found from the town of El Doctor, in the Mexican state of Querétero.

Plate 172 (125) the Cora Indians in villages such as Jusús María, in the Mexican state of Nayarit, wear paper maché masks in their version of the Passion Play, during Semana Santa (Holy Week). This is a Cora mask that I purchased in 1988. The tag indicated that Ruth Lechuga had either been the previous owner or that she had reviewed it for authenticity for the seller. Cordry commented that when he visited this remote area on horseback in the 1930s the Cora had not yet begun to make masks of paper maché.

Yes, this is a Cora mask in the form of an elephant. I can’t explain it, but I feel certain that it is authentic.

Note the cloth stitched around the rim to soften the paper maché edge for the wearer.

Plate 173 (125), a mask carved from the maguay plant and Plate 174 (127), two masks carved from turtle shells; according to Jaled Muyaes, these masks are authentic.

Plate 179 (128) I doubt this one, of a devil with a human body emerging from the devil’s mouth, but my notes indicate that Jaled Muyaes gave it a pass. I suspect that this reflects a mistake in my notes.

Plate 182 (131) this is apparently authentic. The style of painting is certainly traditional in Michoacán, but usually seen on wooden trays.

Plate 183 (132) these are authentic, and Cordry apparently bought them directly from the carver. I really like the furrowed face of the old man mask.

Plate 211(168) this mask with twisted nose and mouth is probably authentic and wonderful. Some Tlacololero masks in Guerrero have J-shaped noses, and the Rastrero (tracker) in the Tlacololeros or Tecuanes dance (jaguar hunters), is often provided with a twisted mouth, so this is evidently a Rastrero mask. Jaled was uncertain about this one.

Plate 212 (169) this is said to be a Rastrero from the Mexican state of Morelos. I agree with Cordry’s statement that such masks are not commonly seen. This appears to be a very nice mask. Here is a remarkable old Rastrero mask from the collection of Charles Thurow.

Note the relief carved ear of this old mask.

Of course the back of this ancient mask reflects the wear that is so evident on the face.

Plate 217 (174) this is an old, authentic, and attractive (if you like Diablo masks) mask. Cordy notes in the caption that this style was replaced with a more modern style that had come into vogue. You can see that new style in Plate 141 (101), and in Plate 306 (247), which is absolutely a modern style mask from Teloloápan Guerrero (and not typical of those made in Michoacán, despite Cordry’s attribution). Here is an older example of a Diablo mask from Teloapan, from my collection.

This is another mask with cloth around the rim to cushion the face of the dancer.

Plate 218 (175) this is a classic Diablo mask for the Pastorela dance from Michoacán. More precisely, this mask, with a lizard over the nose and snakes around the eyes, is in one of the established styles that are found in that state. This is yet another wonderful mask.

Plate 222 (179) Jaled Muyaes was willing to give the benefit of the doubt to the four masks in the second row, and those on the ends of the third row (222 e, f, g, h, i, and l). I don’t like the dog (222e) or any of the rabbits (222f, i, and l). I call your attention to the carving defects flanking the nose of 222f, and under the left cheek of 222i; this is the sloppy carving that I view as highly improbable on an authentic danced mask. I will defer to Jaled on the dog, the chicken, and the owl, although I doubt them all.

Plate 223 (180) shows a detail of a cloth Jaguar suit that was well documented by an important anthropologist, Gertrude Duby. Here is an authentic Jaguar suit and mask from Suchiapa, Chiapas, from my collection.

These suits, worn by boys, have attached leather soles, leather knee pads, and stuffed cloth tails. I tied a knot in this tail because it was so long, but in use it would not be knotted. Note the elaborate cross on the back of the suit.

Plate 243 (198) Caimán for the Dance of the Fish. There are many “body masks” or “step-in” masks of this form in Cordry that are undoubtedly decorative, but Jaled let this one pass as authentic. It is instructive to look at one of Ruth Lechuga’s books—Máscaras Tradicionales de México—published in Mexico City in 1991 by the Banco Nacional de Obres y Servicios Públicos, S. N. C. On page 42 we find a dance photo taken in 1980, in Chapa, Guerrero, in which a masked dancer is wearing such a caimán around his waist. As the authors of the Changing Faces catalogue noted, the decorative masks were likely to be sometimes adopted for use in traditional dances, or they could represent exaggerated copies of traditional masks and accessories. In general, I have the impression that any mask or step-in mask with those pochote spines is suspect.

Plate 264 (215) I believe that this mask is authentic, but it is also true that this design is currently being made for sale, and one sees a number of undanced examples on EBay, which are neither falsely aged or misrepresented. They are handsome masks, in a traditional design. Here is a photo of one of these undanced, made for sale masks from my collection.This is the design that is traditional in Chilapa, Guerrero. I do not know the name of the carver. The wearer looks out through the open mouth.

Plate 267 (217) this is a terrific mask, with its grooved nose that doubles as a rhythm instrument. I have coveted this mask for many years. One can find another example in Caso’s cataloge of a mask show that occurred in 1945 (p 70), said to be from the dance of the Tlacololeros.

Plate 268 (217) this polychrome mask looks like a totem pole element more than a Mexican dance mask. It definitely lacks the design elements that I associate with the decorative masks. According to Jaled Muyaes, it is not only authentic, but Raúl Kampfer stated that this was an earlier form of the Diablo masks from Teleoloapan, Guerrero.

Plate 270 (219) this is a very good mask, but it is not an Angel. This is a female Huehue mask from the Sierra de Puebla, complete with elaborately carved ears. As a matter of fact, the open mouth, with visible teeth, suggests that this is a female clown from that dance. From the angle in the photo, I am unable to recognize the ear design as the work of a particular mascarero, but this mask was definitely made by a master carver from this region. Here is a mask of a beautiful woman from my collection, a Tejonero female that was carved by Aurelio Vásquez about 60 years ago.

This is another mask that had a stained back, so that the wear is revealed by the wearing away of the pigmented finish.

Plate 275 (226) Chilolo masks have a very distinctive design; they all look exactly like this one. This is another one to covet. I wish that I owned one to show you.

Plates 279 and 280 (229), said to be masks from the Dance of the Moors and Christians in Guerrero- the first is old and rare; I have never seen another like it. I feel certain that it is traditional and authentic. The second is also very well carved, and has an articulated (clacking) jaw, a feature that is very popular in the Mexican areas of Guerrero and Estado de México (State of Mexico, the state that surrounds Mexico City). Here is a photo of a Moor mask with an articulated jaw from el Estado de México, from my collection. This dancer wears an elaborate headress, and one can see a dance photo of this character, complete with headdress, in Plate 281 (230) of Cordry’s book.

Plate 284 (232) shows another Moro Chino, with its stylized rectangular projections, and golden beard.

Cordry’s remarks about the mask in Plate 287 (234), when contrasted with his views about the pair of masks in Plate 286 (233) allow us to see again how dazzled he was by the decorative masks, so that he perceived them as older and better than the authentic masks of the same name. I cannot deny that the masks in Plate 286 are handsome, vivid, and engaging, but they happen to be invented. The authentic Archareo (or Alchileo) mask is shown in Plate 287, and it is great. Look at the headdress, topped with this amusing bird. According to Moya Rubio (1986, 63), these masks come from two villages, Colotepec and Pueblo Viejo. Those from the latter village have a cross on top of the headdress, rather than a bird or some other animal. Here is a trio of masks from Pueblo Viejo, from the Archareos dance. I purchased two of these from Robin and Barbara Cleaver in 1988, and the third from Joe Carr in 1992. The two on the sides oppose one another, while the one in the middle is Santiago, marked by his fine beard, and wearing his typical helmet or headdress.This is a variant of the dance of the Moors and Christians, so one sees a cross, actually a human figure in the shape of the cross, on the forehead of the white mask, and a more typical Christian cross on Santiago’s headdress, while the “Moor” lacks a cross on his helmet. The silver foil used to enhance these masks had been obtained from cigarette packages.

Plate 288 (234) this authentic and typical mask has the articulated jaw that I just mentioned in reference to Plate 280.

Plate 289 (235) here is yet another style of Hermitaño, this one from the Mexican state of Durango, with sisal hair and beard.

Plate 290 (235) this is a handsome Hermitaño from Michoacán.

Plate 295 (240), a blowing mask, and 297 (242), a jaguar- these masks were on Jaled Muyaes’ list of decorative masks, but I believe that one or both may be authentic. The mask in plate 295 does not appear to be in the current style for that village—https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KxlBHPi24h8

Plates 298 and 299 (242), 300 and 301 (243) these are all good. Jaled Muyaes noted that the leather mask in Plate 298 is worn by the Perra Maravilla character, in the Tecuanes dance of Guerrero. I would add that the Rastrero (#300) is terrific, and #301 is a good example of the authentic oversized Tlacololero masks.

Plate 305 (246)- I had referred to this great set of masks in my previous post, in reference to a Novio mask by Nalberto Abrahán that had been converted to a Diablo. According to Ruth Lechuga, the masks in this group were all carved by Nalberto.

Plate 306 (247) is, as noted earlier, a typical Diablo from Teleoapan, Guerrero.

Plate 308 (248) is a Diablo in the Tixtla style (see plate 145, page 103). Cordry states that he collected this in 1931. Jaled doubted it; I think it is great, but the horns may be replacements and don’t look right. On the forehead are the three red lines that suggest the mask was made by Nalberto Abrahán (Plate 305, page 246).

Plate 310 (250) this is a remarkable old mask, which Jaled Muyaes identified as authentic. Cordry called it a “mask of death,” but I wouldn’t call it a skull mask, and I don’t know the name of the character that wore this mask.

Plate 312 (252) this is a very simple but authentic Diablo mask from Michoacán.

Next week I will focus on the decorative masks in Cordry’s book.

So much information, so many beautiful masks, so much to take in… keep it coming! What a great resource.

Thank you Tom

Bryan