I published the opening post of this blog on July 7, 2014. Since then it has appeared weekly for two years, for a total of 104 postings (plus one more by a guest). Over that period of time I have had 12,000 individual visitors. Today’s post opens year three. For curious readers who are discovering my site at this late date, such a backlog of articles might seem overwhelming. I myself can generally recall what I have written about, but I am constantly surprised that it was so long ago! For our mutual benefit I have replaced the Index with a “Week by Week” summary that you may access with the Index pull down at the top of this page. You can readily shift to any desired month in the blog by clicking on that month in the Archives on the right side of the home page or on the Index page; there you can scroll through the introductory remarks for the four or five posts that appeared during that month, opening one or another as you please and then backing out to look at the rest. Thank you for visiting and if all this is new to you, welcome to the community of Mexican Mask enthusiasts.

I became interested in Yaqui and Mayo Pascola masks during my first year of collecting Mexican masks (1987-88). For many years I have been intensely studying masks like those I have collected, curious to know about the carvers, the dances, and the masked characters. In the case of the Pascola masks, I have repeatedly visited Yaqui fiestas in Tucson Arizona, I have amassed a library of out of print books on the subject, visited museums, and documented the masks in various private collections. I am working on one or more books about these masks. Today I begin with Yaqui Pascola masks, initiating a series of posts about what I have learned.

The Yaqui Indians, who have lived in the Mexican state of Sonora for thousands of years, call themselves the Yoeme (the People). The plural form is Yoemem. Out of respect, I will frequently refer to them with these names in their language. The Mayo Indians, who speak a nearly identical language, call themselves the Yoreme. In June of 1988 I purchased several Yoeme Pascola masks from Folklórico, a folk art gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico that was owned by Robin and Barbara Cleaver. Here is one of those masks.

I bought this as an anonymous mask, choosing it because I liked its design and patina. I particularly liked the swirling white lines that made up the rim design (the painted elements circling the rim of the mask).

When I visited Tucson for the Easter fiesta in 1991, I met Tom Kolaz, a man who had written an important article about Pascola masks—”Yaqui Pascola Masks From the Tucson Area,” which had been published in the American Indian Art magazine (Volume 11, #1, Winter 1985, pp. 38-45). Although I don’t have a link to that article, I do have one for a follow-up article by Tom that appeared in the American Indian Art magazine in the Summer 2007 issue. Note that although these issues are long out of print, they appear frequently for sale on EBay™.

http://www.yoemecarver.com/aiam07.pdf

At that time, or maybe soon after we met, Tom worked as a member of the curatorial staff at the Arizona State Museum, a remarkable treasure house that is located on the campus of the University of Arizona, in Tucson. Because we shared an intense interest in the Indian arts of the Americas, Tom and I quickly became close friends. I showed Tom photos of my growing collection of Yoeme and Yoreme masks, and Tom was impressed by their quality. He explained that in many cases one could identify the carver of a mask by examining the details of that mask’s design, because excellent carvers tend to develop a systematic approach to their art that is characteristic of their vision. This mask, he said, was obviously the work of a Yaqui man named Román Borbón, who lived on the New Pascua Yaqui Indian Reservation to the west of Tucson.

To make a long story short, Tom became an important teacher as I learned to look at masks from this perspective. He taught me to recognize a number of important carvers, and gradually I began to teach myself to identify others. By comparing this mask to some others by the same carver, I will begin to teach you about this approach. Of course those of you who have been following this blog will undoubtedly remember many other instances when I have applied this sort of analysis to masks from other Indian cultures. It started 25 years ago with this mask!

Here is another view of the Román Borbón mask.

Pascola masks commonly have a cross on the forehead, either carved or painted Often there is a second cross on the chin, but not always, and sometimes there is no cross at all. The mouth of this mask projects an air of solemnity and reserve. Under the chin there is a hole where one of the hair tufts had fallen out and was never replaced. In passing, we will notice that traditional Yoeme human faced Pascola masks never have any indication of having ears.

This mask is 7¾ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3¼ inches deep.

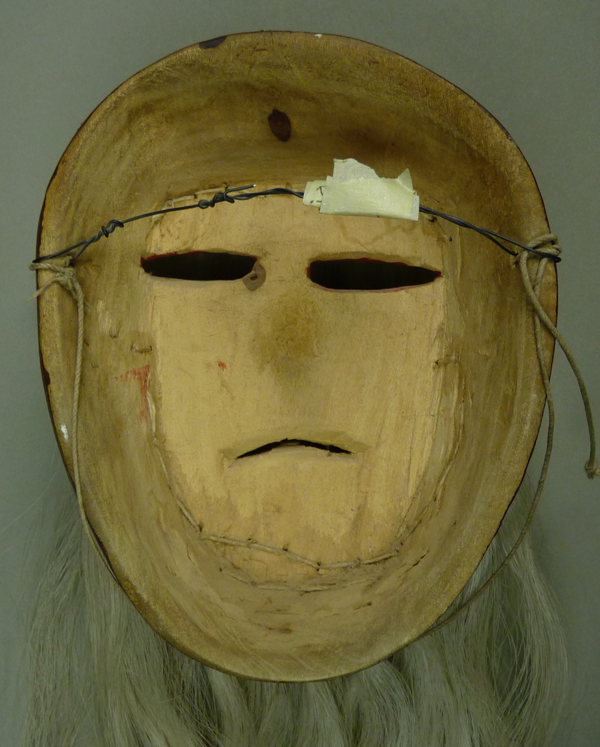

The back view of this mask is interesting at several levels. As we will see by comparison of this back to others by the same carver. Román Borbón often carved the backs of his masks in this severe and stereotyped shape, which reminds one of the shape of a coffin. One can also observe that Román used an auger bit to remove the wood from the inside of the back; the characteristic footprint of such a bit remains visible in this photo. Finally, of course, this view of the back reveals remarkable staining from use, and the soiled strap reiterates this point.

Here is another mask by Román Borbón; this one was purchased directly from the carver by Richard Felger in 1982. I photographed this mask when it was in the collection of Jerry Collings, and he kindly gave permission for me to photograph and then to publish photos of his masks.

An important element of a carver’s style is the overall shape of the mask, while another is the overall color palette. These two masks are quite similar in both of those respects. Likewise they are similar in the rim design, the shape and painting of the eyes, the white triangles under the eyes, the size and shape of the nose, the diagonal white lines over the mouth, and the cross on the chin. On this mask the forehead cross is more elaborate and the carver has given the mask an open mouth. Sometimes a carver will use the same rim design, over and over, but the other possibility is that he will use several different rim designs.

The swirling lines of the rim design are apparent in this side view.

The forehead cross has been outlined with inscribed lines, and then painted.

The back of this mask does not have so severe a shape as the last, but it is not so different either.

If I were to show you a few more masks like this one, you would better appreciate the recognition task. One looks for a typical and limited set of variations that are commonly used by a particular carver, such that no two masks are exactly the same, and yet they don’t look very different from one another.

As it happens, this carver developed a second style of mask, a Viejo type with a wrinkled face, to honor his deceased father. Here is one of those masks, which was collected from the carver by Richard Felger in the 1980s. It was in the collection of David West, the owner of Gallery West, in Tucson, when I took this photograph; he has kindly given permission for me to photograph and publish photos from his collection.

This mask is quite handsome and striking because of the inscribed lines that suggest the wrinkled skin of old age. This is a relatively unusual stylistic element, which is a particularly specific marker for this carver. Masks in this style by Román apparently emerged on the faces of Tucson Pascola dancers in the 1960s.

This mask is interesting for the use of mirror fragments to create the forehead cross. I also call your attention to the jutting chin, a feature that sets these Viejo masks apart from Román’s other human faced masks.

On this mask the carver has allowed the carved wrinkles to dominate the design, and he has omitted any rim design.

This mask is undoubtedly by Roman, but for some reason he has softened the lines of the back edge. There is significant staining from use.

Here is a second example of this type of mask by Román Borbón. This one was collected from the carver by Richard Felger in 1981. It is currently in the collection of the author.

In this case Román has provided an inscribed line to create a simple rim design. We see again the prominent chin that accompanies this style.

This forehead cross is recessed, carved to a level below the surface of the forehead.

This mask is 8¼ inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

In this instance we again encounter the carver’s severe shaping of the back, which is heavily stained from long use.

Now I will show a child’s monkey mask that came to me without a carver’s name. I bought it from Robin and Barbara Cleaver in 1989. It was collected in Hermosillo, Sonora and I have attributed this mask to Román Borbón, who was from Hermosillo, because of the carved wrinkles on the face, which so closely resemble those on the Viejo masks. The white diagonal lines flanking the nose and mouth are also typical of Román’s style.

The color palette and the informal paint is similar to what one sees on some of Román’s documented masks.

This mask is 7 inches tall, 4½ inches wide, and 2½ inches deep.

The shape of the back does not remind one of Roman’s style, but because this was made for a child rather than for an adult with a longer face, I have ignored that difference.

I will end with another child’s Pascolola mask. This one was not carved by Román Borbón, but rather it was carved for his use when he was a child. The carver was Laureano Castillo of Hermosillo, Sonora. When this mask was collected from Román in 1981, Román stated that he began dancing with this mask at the age of 6, in 1936. Laureano would have been 82 years old at that time. This mask is another from the collection of David West (Gallery West).

It is intriguing to look at this mask as a potential model for Román’s carving style, because we see the same crosses, the same color palette, and even these unusual inscribed lines on the face. At any rate, this is a handsome and interesting old mask. It is highly unusual to encounter such an old and well documented child size Pascola mask.

One is particularly aware of the remarkable shaping of the face of this mask from this angle.

The wear from Román’s long use of this mask is obvious.

There is mild damage along the left edge from former insect infestation. On the other hand, the patina from long and intensive use is striking!

Next week I will introduce you to another Yaqui mask carver and his masks.

Wow, your information and pictures were informative. I was reading a vintage IndianArts Exhibition catalog from 1971 Scottsdale AZ show, and it mentioned Pascola Masks. Thank you for your research.

Just came across your very infomative Website while doing research on Yaqui masks. I recently acquired two Yaqui masks that appear to be from the 1930s. May I send you photos for your opinion?

I have a wooden mask found in the desert of Sonora. If I sent a picture would you be able to tell which tribe it was. Thanks Aletha