This series of posts about Yoeme (Yaqui) Pascola masks began on July 4, 2016.

When I began attending the Yaqui Easter fiesta in Tucson, Arizona, beginning in 1989 and continuing over the next 25 years or so, I quickly discovered another Yoeme carver—Antonio Bacasewa. Although Antonio lived in Vicam, Sonora and he did not often travel to Tucson, his masks were widely available in Indian arts stores there, because they were being brought up from Sonora by some important Indian traders, Barney Burns and Mahina Drees. I will tell much more about that couple in a future post.

Antonio Bacasewa’s masks are notable because, although they were made for sale to whomever might want them, they were carved creatively in traditional designs from the usual wood—raíz de Álamo (cottonwood root). Furthermore they were smoothly finished and of normal size. That is, they were perfectly appropriate for dancing, and dancers frequently did buy these masks for their own ceremonial use. Yet Antonio’s masks were also inexpensive and interesting enough to attract tourists and collectors. While some other carvers made different styles of masks for these two potential markets, as I will vividly demonstrate in future posts, Antonio produced a uniform product that was suitable for both. I view Antonio as an important and innovative folk artist. He died in 1991.

Here is one of those undanced masks that I purchased from an Indian arts store in Tucson. I liked them so much that I bought many of them, over the years.

Note the graceful line of the cheek. I suppose that the animal painted on the side of the mask is a scorpion, or maybe this is just a lizard. From this angle the design of the mouth is interesting, even if anatomically doubtful. I cannot look at this mask without imagining a character with this face in the rain, catching raindrops with his extended lower lip. This is of course my own idiosyncratic idea, but it is grounded in the knowledge that the Yoemem (Yaquis) consider rain to be a sacred gift from the Sea Ania (the Flower World).

Antonio was an excellent carver, but he invented anatomical details to suit himself, rendering those features in an abstract fashion. In this case he imagined a person with prominent upper teeth, but it suited him to dispense with the possibility of lower teeth. The effect of this is charming. He does something similar in the next mask, although they do not look at all alike.

My friend Tom Kolaz had actually visited Antonio at his home in Vicam, Sonora. He emphasized to me the value of a particular design feature that was most specific to this carver’s work; Antonio took pains to insert small wooden wedges or pegs at the base of each hair bundle, for the purpose of spreading the hair into a fuller display. If you look closely at the first photo above, one can just barely see one of the wooden pegs, below the scorpion’s back foot.

Although there have been other carvers who used pegged hair bundles, this feature is often diagnostic for this carver, particularly when one encounters an unusually handsome mask that rises above Antonio’s everyday standard, leaving one to wonder which master had carved it. In the coming weeks I will illustrate some masks like that. Here are better photos of the pegs, first as installed in the brow hair, and then in the beard. Slim and flat, they resemble matchsticks.

The pegs are most clearly seen in the hair bundles that make up the beard.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 5¼ inches wide, and 3¾ inches deep.

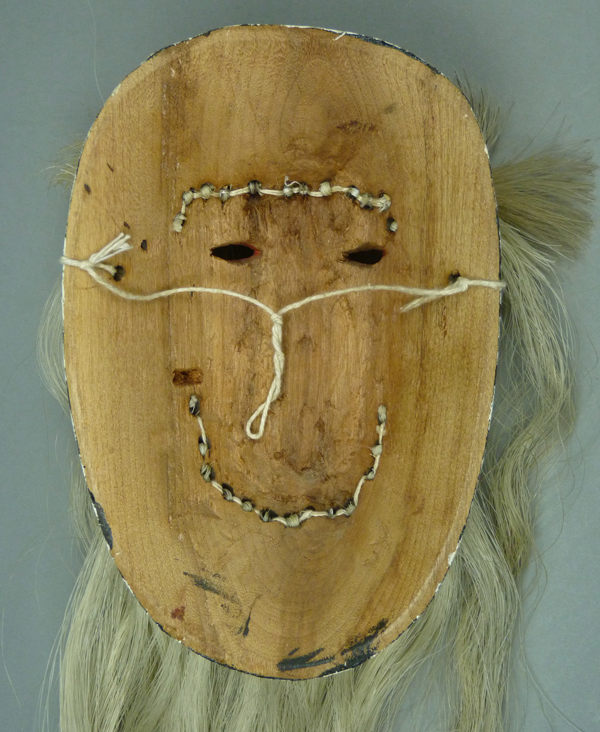

The back of this mask is very smooth, and of the appropriate size to accommodate the human face. As carved, Antonio’s masks were ready to be worn by a dancer. As you can see, the hair bundles are drawn tightly through small holes on the face of the mask and then laced in place with string across the back surface. The wooden pegs are unnecessary to secure the hair, but they serve to spread the hair, according to Tom Kolaz.

It occurred to me that you might like to see Pascolas dance. In this first YouTube™ video the Pascola and the Deer Dancer, who are children, perform to music on the flute and drum, music that dates back to the time before the arrival of Europeans. Then as the Deer dancer prepares to enter the dance, the Deer singers begin to play their wooden raspers, which will provide a rhythmic background for their singing. The booming drum sound when the Deer singers perform is provided by a “water drum,” a half gourd floating in a basin of water that is beaten with a stick wrapped in corn husks; if you watch carefully, you will see the water drum in action. The Deer singers sing in the Yoeme (Yaqui) language and their songs are about the animals, plants, and elements of the Flower World.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lyWJLbVa4zw

In this second video, from the Yoeme village of Cocorit, seasoned older dancers perform, first one and then another. Note that they engage in clowning when they are wearing their masks turned from the face. For example one shouts with excitement as his masked colleague is dancing. Later that Pascola also dances. After he stops dancing and turns his mask from his face, then he dances behind the Deer dancer in a clowning fashion, as if the two are in a rumba line. Again, the deer dancer dances to the singing, water drum, and raspers of the Deer Singers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3F4LjHt60Q

Here is a Yoeme rasper. It consists of a notched stick, a second stick that is used to scrape against the notches (both carved from Brazil wood), and a half gourd that amplifies the sound.

You can read about the Deer Songs in a wonderful book—Yaqui Deer Songs/Maso Bwikam: A Native American Poetry, by Larry Evers and Felipe S. Molina (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990).

The dancing in the third video occurs to a wonderful European style song that is very popular among the Yoemem. When dancing to this style of music, the Pascola turns his mask to one side or wears it on the back of his head. The music is provided by a fiddle (melody) and a harp (rhythm of the sort offered by an upright string bass). In this video the Pascola dancer wears his mask turned to the back of his head and he dances in an entirely different style, essentially European tap dancing. During this style of dancing, neither the Deer dancer nor the Deer singers participate.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V2vUl5O_OP4

Here is another one of Antonio Bacasewa’s made for sale masks.

We see another abstract and stylized mouth.

In this side view, one can again see one of the wooden pegs that Antonio inserted next to each hair bundle; look just above the left corner of the mouth.

This mask is 8½ inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

It is immediately obvious that this mask has never been danced. All of Bacasewa’s backs are as well carved as the two you have seen, so I will show some more masks without including photos of the backs.

Looking at a third mask, I can begin to point out some general features of Antonio’s style. Usually the rim design, the forehead cross, the triangles under the eyes and the designs on the cheeks are all painted freehand, without any inscribed lines to define the edges. However on this mask the triangles of the rim design have inscribed edges, as will be apparent in the photo that follows this one. Antonio usually used only black, white, and red paint, unless other colors were necessary for the cheek designs.

The mouth on this mask has upper and lower teeth. The mask is 8 inches tall, 5¼ inches wide, and 3¾ inches deep.

We see a snouted lip. A fat frog or toad is painted on the cheeks.

A fourth mask has a protruding tongue.

The triangles of the rim design are inscribed. Again we see the graceful curve on the cheek of this mask.

This mask is 8¼ inches tall, 5¾ inches wide, and 3¾ inches deep.

The fifth made for sale mask has a silly expression.The triangles that are usually under the eyes have been extended upward to enclose the openings for vision.

This mask is 9¼ inches tall, 5¾ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

This mask has an unusual forehead cross; the arms of the cross look like seeds. This time the triangles are outlined by inscribed lines.

Here is the last mask in today’s post. It presents a mixture of familiar and unfamiliar elements.

This mask is 8½ inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

On the cheek is another one of those creatures with the curling tail.

By now you may have noticed that Antonio preferred not to make the same mask twice.

Next week I will compare old and worn goat Pascola masks by Antonio to other more recent ones that he made for sale.

Awesome human type Hiaki pahko’ola mask’s(old man of the ceremony).i am yaqui from Guadalupe az,and I grew up in the hiaki culture.i love my tradition that my ancestors left to us.pascola dances are so cool to watch.

Benjamin,

Thanks for visiting. I agree that Antonio Bacasewa’s masks are awesome and I too have enjoyed seeing Yaqui/Hiaki Fiestas for many years, mostly in Tucson but a few in Guadalupe.

Bryan Stevens