Last week I introduced two Indian traders, Barney Burns and Mahina Drees. Today I continue their story.

Barney Tillman Burns died on August 14, 2014. On October 2, 2015 a mutual friend told me that Mahina Drees Burns was looking for someone to help her to organize and photograph the collection of masks that she and Barney had assembled over a period of decades. Of course I indicated my strong interest. On March 10, 2016 I flew from Pennsylvania to Tucson at Mahina’s invitation to photograph the masks. I was there for nearly two weeks. A wonderful friend, Wade Sherbrooke, loaned Mahina and me his garage to use as a studio. As it turned out, there were at least 768 masks (plus a few more that Mahina discovered after I had returned to Pennsylvania); of those, 409 were Yaqui. Here is a photo of my garage studio.

The next photo is the view from Wade’s back yard of the land outside of the garage. This is a mountain adjacent to Saguaro National Park West.

Going into this project, I really didn’t know what to expect. Mahina and Barney had actively collected danced masks, put them away in boxes, and moved on to their next tasks. Would the masks prove to be old or recent? Would I encounter carvers who were otherwise unknown to me? Would there be masks by identified carvers that allowed me to identify anonymous masks in my own collection? And vice versa? In fact, most of the masks dated to the last 30 years or so, I discovered some carvers who were new to me, and I did make many connections between anonymous masks and others that were well documented.

However, the greatest benefit was that I gained an entirely new perspective on Yaqui mask use in Sonora. If you think about it, my exposure to the Yaqui scene in Tucson, Arizona provided but an indirect window on the larger culture in Sonora. Dancers and masks came up to Tucson, but observation of those visitors and masks could only be suggestive. In contrast, this group of Sonoran danced masks provided an unexpectedly richer picture. For one thing, there were so many danced masks collected during recent decades, revealing the persistent strength of these dance traditions. Furthermore, the masks themselves were so interesting, and in an unexpected way. In comparison to the made for sale masks, the danced masks by the same carvers were a little larger, a little heavier, and most tellingly, they were often simpler in their design.

So I thought that I would continue posting about Yoeme Pascola masks and carvers by either comparing made for sale masks to danced masks by the same carver, and/or by simply celebrating other carvers whose masks are primarily traditional and danced, in either case mixing the masks I recently photographed from the Barney Burns and Mahina Drees collection with others in my collection or in other collections accessible to me. In this post and the next I will focus on a comparison of made for sale and danced masks by Rodrigo Rodriguéz Muñoz, the carver of the first mask in last week’s post. Here is a made for sale canine mask that was collected in 2005.

As you will later see, this made for sale mask and the next have much in common with the traditional examples that follow them. It has the same flat forehead and the same forehead cross, similar eyes, and a similar rim design.

The designs are outlined by inscribed lines.

The teeth are very carefully carved.

This mask is 8½ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 2¾ inches deep.

The pencil inscription on the right edge of the back reads “Mexico, 1/05, RR.” The actual back is barely wide enough to cover a dancer’s face.

The second made for sale canine mask appears to portray an animal more savage than a dog; I call it a wolf.

Triangles of mirror glass are inlaid on the cheeks.

The forehead cross is uncharacteristic for this carver, but entirely within the norm for other Yaqui carvers, and not unlike those of his uncle, Conrado.

As in other examples of Rodrigo’s made for sale masks, the hair is substandard in comparison to one of his masks that was intended for dancing.

This mask is 9 inches tall, 4¾ inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back of this mask is adequately carved to accommodate a human face, but well below the shaped backs that Rodrigo provided for dancers. However, it was not Rodrigo’s impression that he was producing a mask that would be danced. On the back is written “RRM, 1/98. Mexico.”

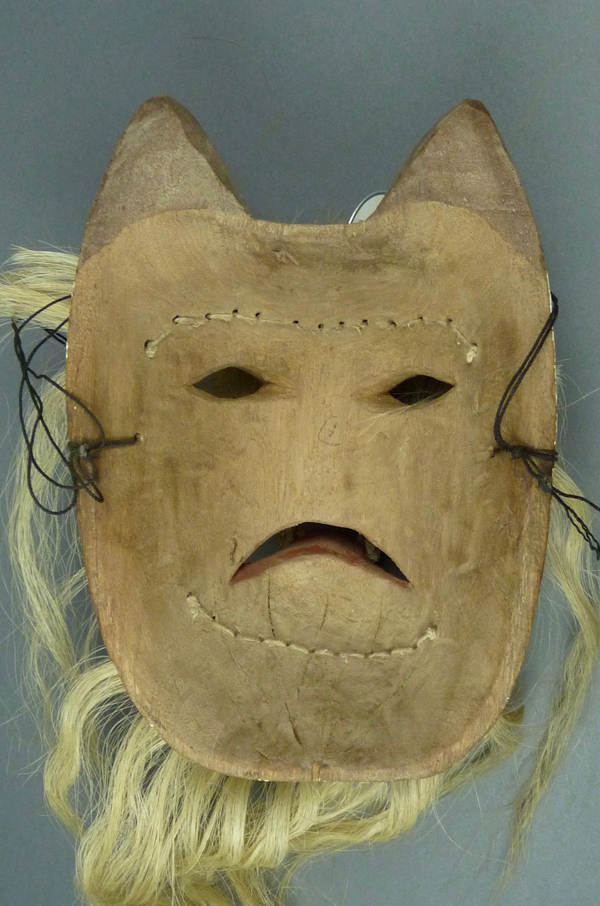

Now we will examine a pair of canine masks by Rodrígo that were actually danced for 8 to 10 years.

Holding these in my hands, the observation that struck me was that these danced masks were larger and heavier, and that they had more mass.

They also seemed less decorated and more spare. Yet the detailing of the toothy mouth of this mask makes it far more realistic and menacing than the mouths of the two made for sale canine masks above.

The flat forehead and this cross of four triangles remain consistent across most of Rodrigo’s masks, whether made for sale or intended for dancing.

The back of this mask has been carefully smoothed to insure the dancer’s comfort, the open mouth would provide copious air to the dancer’s mouth, and the rim is stained from contact with the dancer’s face. Note the difference in the shape of this mask, compared to that of the two above.

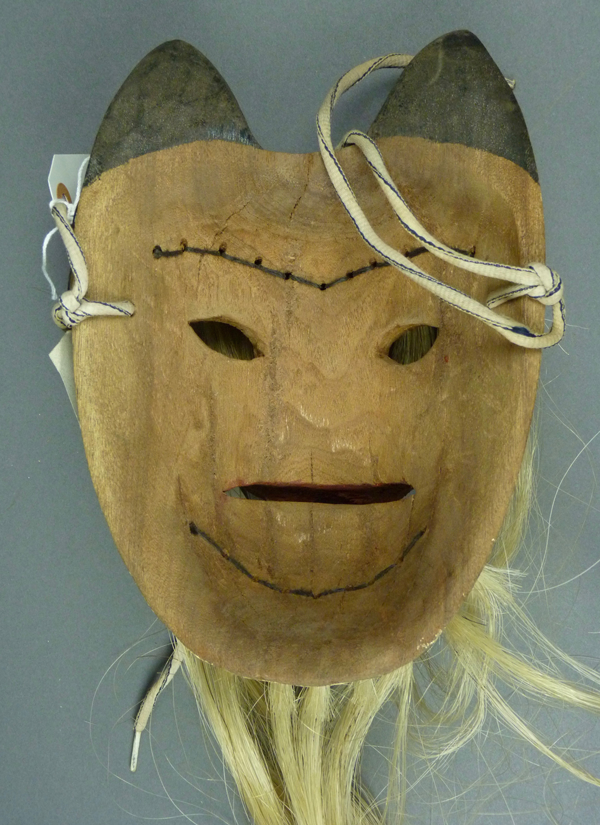

Here is a second danced canine mask by Rodrigo.

Again we see simplicity of decoration and form, but dramatic shaping to create an impressive face.

The hair is better than on the made for sale masks.

An excellent passage for air is difficult to see from this angle, but obvious from the back.

One can see that this mask has been danced.

I will end this post with a bonus made for sale mask by Rodrigo Rodríguez Muñoz that is unlikely to be matched by a danced example. Exactly what does this mask portray? Although this looks like an elephant, it lacks any indication of that creature’s tusks or flapping ears. Probably this represents some sort of Tejón (wild animal) such as an anteater, or coati? Coatis are found throughout Mexico and they do have elongated turned up noses, while anteaters are found in Southern Mexico and down through South America, but not in Sonora.

Many familiar Rodriguez elements are apparent on this mask, with the exception of the nose.

The forehead cross is unconventional and playful for Rodrigo, but there was no intended dancer to protect with a serious cross.

Well, is this mask appealing, or what? There are traveling circuses in Mexico, and they do have elephants, so although an absurd subject for a Pascola mask, elephants are probably not unknown to the Yaquis. On the other hand, I am more inclined to wonder whether this is a portrayal of some animal from the desert world of the Yoemem.

This mask is 8½ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 5½ inches deep.

This mask was collected by Barney and Mahina from Rodrigo Rodríguez Muñoz in January, 2000. It is of course undanced, and the back has the same shape as the other made for sale masks.

Next week I will compare made for sale and danced examples of human faced masks by Rodrigo Rodríguez Muñoz.