This series of posts about Yoeme (Yaqui) Pascola masks began on July 4, 2016. In this third post about the masks made by two brothers, Preciliano Rodríguez Cupis and Conrado Rodríguez Cupis, and largely drawing on the Burns collection, I will focus on masks that appear to have been made by Preciliano; some turned out to be by Conrado. I begin with a mask that Rodriguez family members attributed to Preciliano. It was collected by Barney and Mahina Drees Burns in 1996 (B/M 451/442).

Looking at the full frontal view, I notice the design of the eyes (thin vision slits under painted eyes), which is typical of Conrado or Preciliano.

There are inlaid triangular mirrors under the eyes, a feature you have seen before on the masks of Rodrigo (August 29, 2016), Jesús (September 19, 2016) and Conrado (October 10, 2016).

The face is nicely shaped, and there are gigantic inscribed insects on the cheeks.

The whirling cross on the forehead is particularly popular with the son of Preciliano, Jesús; probably one learned it from the other. The rim design is of a familiar Rodríguez style, in which small and large triangles are arranged in a sequence (VVvvVV).

A small inscribed cross on the chin looks like a flying bird. I suppose that this cross was added by a dancer.

The back demonstrates mild staining from use. Although it was collected 7 years after it was made, it doesn’t seem to have been danced much. The vision slits, being so narrow, would not have endeared this mask to a dancer. A really interesting touch is the artful carving of the nostrils on the back surface; in Mexican masks, it is usually the vision slits that receive such attention.

The next mask is one that I purchased on EBay™ as an anonymous mask in 2010; my friend Tom Kolaz later informed me that it had been made by Preciliano. Now that I have studied the masks in the Burns collection, I agree that this is likely to be correct. As you will see, this is a mask that has been heavily danced. One reason that I am showing this mask is because it serves as a good introduction to some others in the Burns collection.

One feature of this mask that is worth noting is the mouth design. The faces of the upper teeth are carved and painted, but if we were to look through the opening of the mouth, then all we would see is a flat or slightly curved palate that is painted pink. This manner of handling the teeth and palate is often seen on masks by Preciliano. The nose design on this mask is also typical for this carver, and much like the one on the last mask, as one alternative to his dramatic and exaggerated hooked noses.

Preciliano is one of several Potam carvers who have used this rim design. From this angle, also note the shape of the eyes—rounded on the inside edge and pointed on the lateral end. Of the Rodríguez carvers, Preciliano uses this eye shape much more than the others do, but sometimes his eyes are pointed or round on both ends.

The forehead cross is one that Preciliano liked to use, but it was popular with others in his family too.

This chin view demonstrates what I was saying about the teeth and palate design; the teeth are not carved and painted in three dimensions. You can see this on the first mask above, but it is less obvious.

The back has the narrower profile that is typical for the masks of Preciliano, while those of Jesús and Rodrigo tend to be broader and more rectangular. There is marked staining from use.

Barney Burns and Mahina Drees purchased the next mask from a carver in Potam, Inez “Cheto” Álvarez, in 1996 (B/M 392/383). Cheto stated that he did not know who carved this mask, but he was told that it had been danced for 22 years by Norberto Coronado. As you will see in later posts about the masks of Manuel Centella Escalante and those of Cheto, both made masks in this style, and one could say that this mask is a good example of a Potam type. But for Cheto’s denial, one would have considered the possibility that he was the maker, and Tom Kolaz even wondered whether it had been made by Centella. But to my eye, after studying the Burns masks, this one looks like a Rodríguez piece. Then, if one compares the teeth on this mask to those on the last, we see that this is a mask by Preciliano. Neither Cheto nor Centella make teeth exactly like this.

The eyes have the shape favored by Preciliano. Although the division of the triangles under the eyes into two colors is characteristic of Centella, he favored white triangles with red centers, and usually created a matching triangle over the eye. The design and painting of the nose is also characteristic for Preciliano. The inscribed lizards on the cheeks are generic.

The size and formality of the forehead cross makes me think of the Rodríguez family, and this design is not exactly like those by Centella or Cheto, even if it is somewhat similar.

A chin cross with a hair tuft in the center is unusual for Cheto, Centella, or the Rodríguez carvers, but the latter do favor such a degree of formality.

From this chin view, the teeth in Preciliano’s style are easily seen.

The shape of the back of this mask is consistent with attribution to Preciliano. It is unusual for the back of a Yaqui Pascola mask to make any special accommodation for the nose, but here we find a shallow triangular recess. The wear on the back of this mask is marked, as if it had indeed been danced for 22 years.

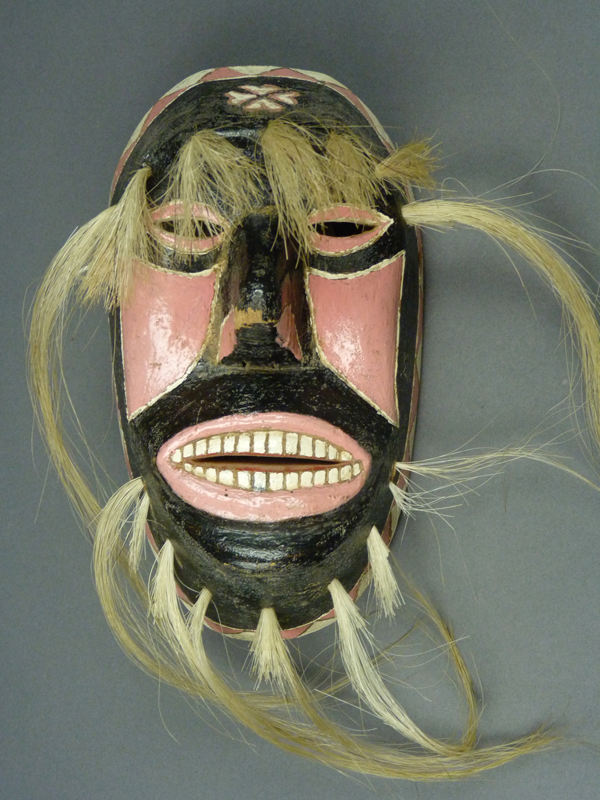

Here is a somewhat similar mask that is even more difficult to assign, because at first glance one is most reminded of the hand of Inez “Cheto” Álvarez, and the Rodríguez family actually attributed it to Cheto. On reflection, both Tom Kolaz and I agree that it is the work of Preciliano. In this case the front of the mask is moderately convincing, while the back design erases all doubt. This mask was collected by Barney and Mahina in 2004 (B/M 847/842).

The eye design alone forces one to think of Preciliano; there is not only the shape but also the delicacy of the opening within that shape. A surprising aspect of the mask, from this angle, is the convexity (the bulging contour) of the triangles under the eyes. The formality of the mouth and teeth also point to a Rodríguez hand, and more particularly that of Preciliano. The hot pink paint always makes me think of Cheto first, as he favored this color along with others of equal brightness.

The forehead cross is sufficiently non-traditional to also remind one of Cheto, but here it is on a Preciliano mask.

From these views one can see the shelf-like surfaces directly behind the facades of the teeth, a Preciliano characteristic.

In this instance there is no chin cross.

As Tom Kolaz noted, this is a Preciliano back, and NOT a Cheto back. In a future post I will show an imitation of a mask like this by Cheto, and that mask does have a Cheto style back. But today my goal is to sharpen your appreciation for the masks of Preciliano, one of the most impressive of the Yaqui master carvers.

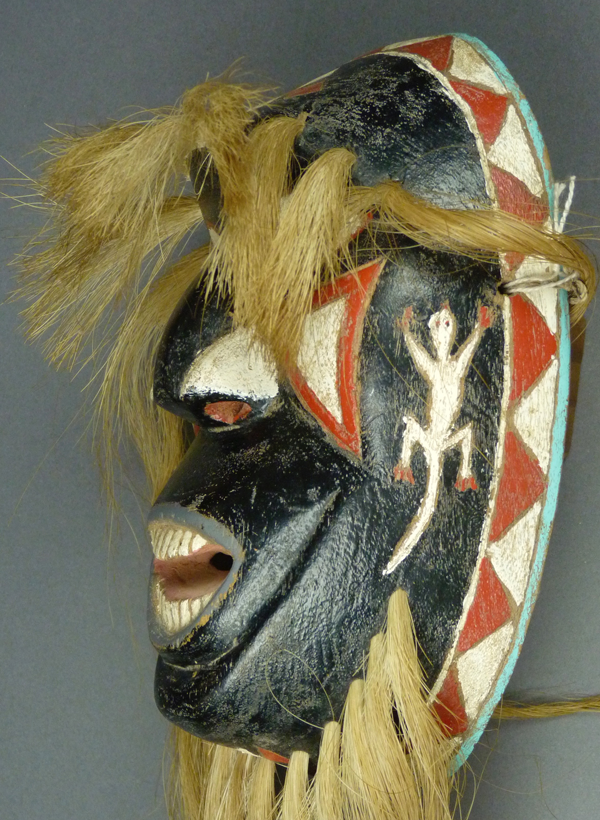

The next mask was attributed by the family to Preciliano at the time of sale to Barney and Mahina in 2005 (B/M 335), and a cursory glance does reveal several features that I associate with that carver. Yet, this is a less elegant example of his work than the many mis-attributed Preciliano masks that you have already seen. The eye design is certainly his favorite, there is a wonderful oversized nose, the triangles under the eyes are long and curving, the mouth design is less careful than usual but nevertheless typical, and the rim design is of the proprietary Rodríguez form (VvvvvvVvvvvvV).

Reviewing this post, my friend Tom Kolaz noted that a nose this large, in association with the extra large triangles in this hybrid rim design, mark a mask by Conrado. Ironically, he added that Preciliano’s masks tend to be more finely carved than Conrado’s, reinforcing my comment that this one didn’t seem to rise to that standard. Since this is an area where Tom is more experienced, I duly admit my error and post this correction.

The morning stars framed by circles on the cheeks are bounded by inscribed lines, but they are jammed into the space between the rim and the triangular tears; I doubt that they are original. I suspect that there were white morning stars that have been repainted and enclosed by green circles. Regarding the rim design, note how much larger the taller triangles at the temples are, in comparison to those next to the corners of the mouth, or to those at the beginning of this post. It is these super large triangles that mark a mask by Conrado, according to Tom Kolaz (VvvvvvVvv).

From the side, just look at the magnificent oversized nose, beyond the size of any nose by Preciliano. The mouth design resembles those of Preciliano, yet it is less finely carved.

The forehead cross seems an even more unfortunate addition; it may cover a more delicate design.

Note the prominent thin blade of the nasal ridge. The nostrils are unusually well carved (for Conrado). The rim design continues around the chin, as expected, and as usual there is no chin cross.

Although this mask was said to have been danced for 7 years, the wear on the back is mild to moderate. Sometimes this reflects the dancer having scrubbed the back before selling, due to hygienic concerns. There are good air passages and adequate vision slits. Such well-carved nostrils are more typical of Preciliano.

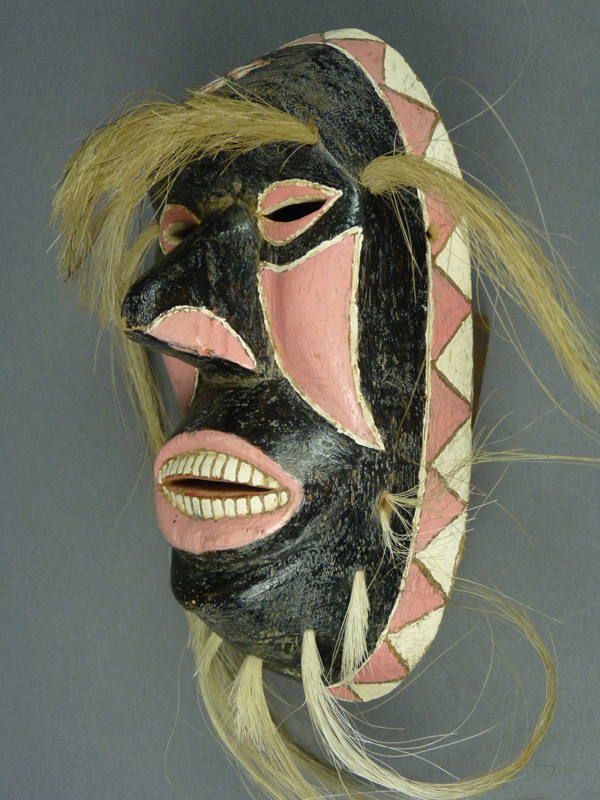

In last week’s post, I showed a number of masks attributed to Preciliano that had long slender hooked noses, accompanied by geometric or faceted features. The next two masks have geometric features, but without those dramatic noses. The first, which was presented as the work of an unidentified carver, was collected by Barney and Mahina in 2008 (B/M 333/326). It has a forehead cross that I associate with Preciliano, along with his eyes and these geometric features. The mouth on this mask follows his usual form, although the teeth are more three dimensional. I am uncertain that Preciliano did carve this mask; there is the possibility that it was carved by Conrado. The two masks differ slightly, and this one is definitely more refined in the carving details, compared to the next.

This hybrid cross, with Maltese vertical elements and flower petal arms, appears to be a marker for Preciliano.

The nostrils are carefully defined and closely resemble those on the last mask, while the teeth are individually carved.

In this detailed view of the left cheek that follows, Preciliano’s usual eye design is apparent, as are the teeth. A carved sloping bank separates the nose and mouth from the cheeks, creating a gutter, and creasing the triangles under the eyes, which seems particularly elegant! This is an unusual and striking feature, which like other geometric experiments found on Preciliano’s masks, emphasizes the prominances over the cheekbones.

This next view reveals that the carved sloping bank almost functions as a cross section of the right cheek, emphasizing its curving surface.

The back demonstrates considerable staining from use.

I would have thought that the next mask was clearly by the same hand as the last, but Tom Kolaz again noticed the very large triangles in the rim design as Conrado’s. It has the same eyes and almost the same geometric cheeks, but less elegantly carved. The nose has unusual geometric planes, making me think of Preciliano, but the mouth and tongue are crudely carved. The forehead cross is one that was favored by Preciliano and Conrado. Barney and Mahina collected this mask in 2005 (B/M 346/339). It had been attributed by the family to Conrado Rodríguez Cupis, I wondered if it was actually made by Preciliano, but Tom Kolaz sees Conrado’s hand. These two masks illustrate the overlapping styles within the Rodríguez family, so similar and yet so different.

In the view that follows, one sees a flat spot over one of the nares. All of the triangles in this rim design are very broad and tall.

By now this is a familiar forehead cross.

On this mask the carefully carved nostrils don’t open to the interior of the mask.

Note the crude carving of the tongue, and the uniformly large triangles around the chin.

The back is stained from significant use. This mask was said to have been danced for 13 years.

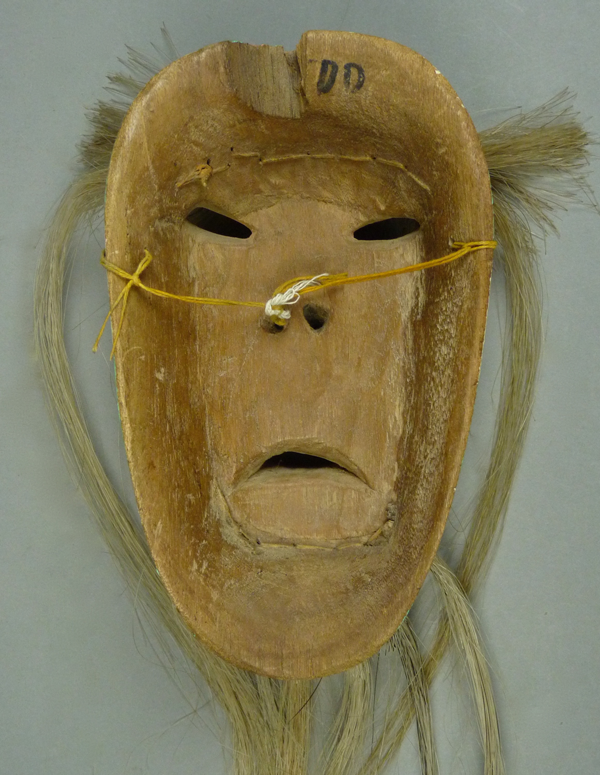

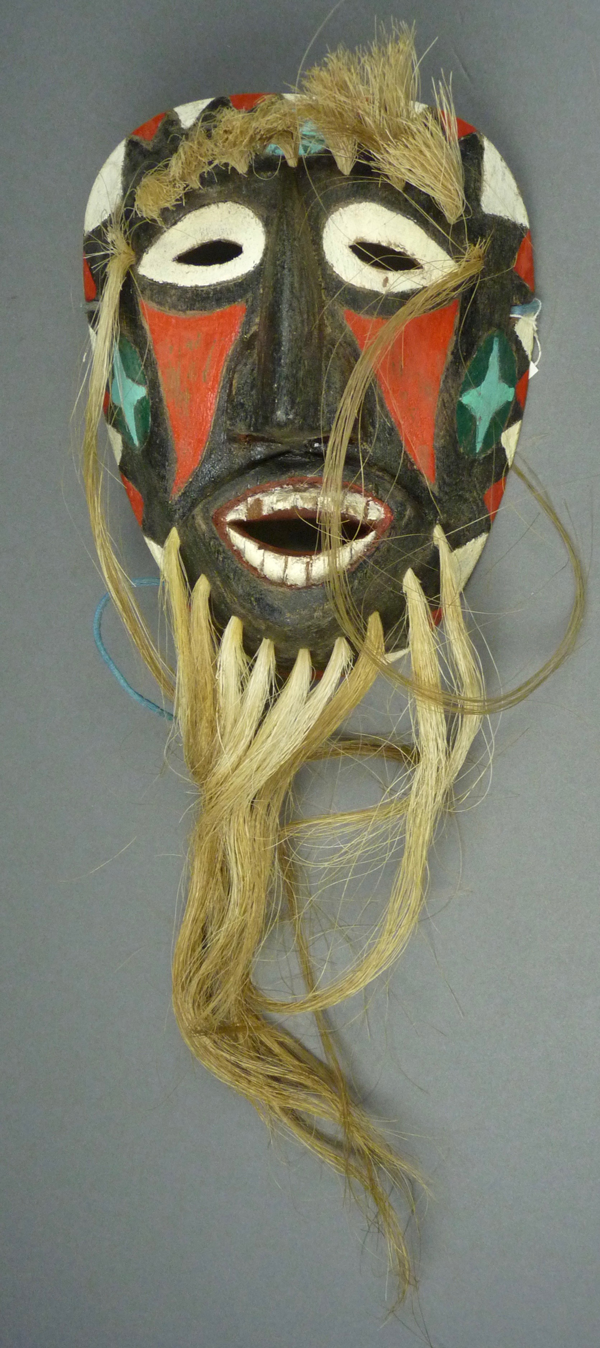

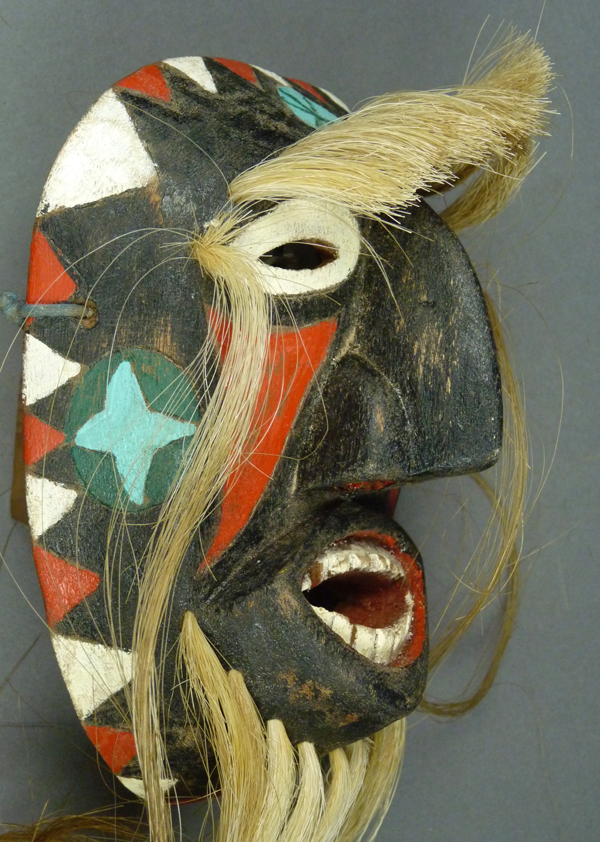

Next is an unusual canine mask that was attributed to Preciliano by his family. (B/M 431/422).

The eyes appear to follow Preciliano’s usual design.

The forehead cross has a hybrid design of the sort favored by Preciliano, while the overall shape brings the masks of Jesús to mind—father and son.

There are no air passages in the nostrils or in the mouth, making me think that this mask may be the work of Jesús and not Preciliano.

In the back view, holes for air passages through the nostrils were initiated, but never drilled. I don’t know why.

The back is consistent with Preciliano’s work. This mask was said to have been danced for 13 years, and there is marked staining from use.

The last of today’s collection is another of those long nosed masks like those in last week’s post, but this one lacks the geometric facial features. It was collected by Barney and Mahina in 2005; at that time it was one of many in this style that were unaccountably attributed to Gerardo Barcelo (B/M 471/463).

This minimally decorated mask has such a powerful presence.

We find another one of those hybrid crosses with flower petal arms.

The white arm appears to have been clipped to accommodate the limited width of the forehead, as if intended to suggest a cross of four petals.

The tip of this nose is so sharp, echoing the shape of the corners of the eyes.

The shape of the back is consistent with other backs by Preciliano, but unlike those of Gerardo Barcelo. On the other hand, I cannot entirely rule out Conrado. This is another mask with scant ventilation. There is moderate staining from use, and this mask was said to have been danced for seven years.

I hope that you have enjoyed seeing the Pascola masks of Preciliano and Conrado. Next week we will examine some more masks by Conrado Rodríguez Cupis.