Janet Brody Esser studied the masks and dances of this region of Michoacán during the period from 1970 to 1975. Her doctoral dissertation on this research, Winter Ceremonial Masks of the Tarascan Sierra, Michoacan, Mexico, was published by University Microfilms in 1978 in two volumes. A book based on this research followed in 1984—Máscaras Ceremoniales de los Tarascos de la Sierra de Michoacán, published by the Instituto Nacional Indigenista, in Mexico City. The advantage of the latter book is that it includes many of the same photos as those in the PhD thesis, but because these are printed rather than photocopied, they are better images. In these volumes Esser described a variety of related traditions, which reflected local customs and individual carvers. The masks in today’s post will illustrate some aspects of this variety. One focus of Esser’s research was on the masks of the Viejos, or Curpites (Esser 1978, pp. 60-134; 1984, pp. 57-121).

When Dinah Gaston visited Zacán, Michoacán in the 1990s. she met an elderly carver there, Alejandro Sanchez Mercado Senior. She purchased masks that were made by Señor Sanchez Mercado for the Curpites dance and subsequently danced. Later she sold those masks to me, one by one over a period of six years. They are of interest because they look fairly different from those of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro. At some point she bought several much older Tarépiti masks that had been repainted as Negritos/Blackmen, and I bought one of those. In the Máscaras Purepechas Catálogo 2002 survey there are masks by Alfredo Sánchez Mercado of Zacán, who may be the son of Alejandro.

Here is the trio of masks that were purchased directly from the carver, Alejandro Sanchez Mercado Senior, by Dinah Gaston. I took this photo to demonstrate the disparity in their sizes. Maringuilla (on the viewer’s left) is so small in comparison to the Curpite (on the viewer’s right).

Here is Tarépiti, or Grandfather. Note how different he looks, compared to the comparable masks from Nuevo San Juan. I bought this mask from Dinah Gaston in 2006. She had held him in her personal collection for years, out of affection for this elderly carver.

Look how wrinkled and somber this mask is.

Although this mask seems initially less impressive than those of Nuevo San Juan, on repeated examination it is more touching, and certainly very well carved. It is 8½ inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The back is impressively stained from use.

This is the Maringuilla mask that Dinah Gaston bought directly from the carver in the late 1990s, and I bought it from her in 2002.

One is struck that this Maringuilla is so plainly carved; she lacks glamour, despite her dimples!

There is nothing ugly about this face, it is carefully carved, but yet the expression is so serious. Photos of the Zacán Maringuilla that were taken by Janet Esser in 1975 show an equally serious Maringuilla (Esser 1984, pp. 85, 90). It seems that in Zacán there is a deliberate emphasis on the serious appearance maintained by these dancers on Christmas eve and then on the following day, whereas in other towns the masks seem to reflect the gay, playful nature of the Curpites performance that follows in January. Esser commented (1978, Volume I, pp. 41-44, 92) that all of the Vieos/Curpites dance to fulfill a manda (vow of service to a Christian Saint or to God) and so grave behavior is appropriate, particularly on Christmas Eve. This mask is 7 inches tall, 5¼ inches wide, and 2¾ inches deep.

The back shows definite staining from use, and there are the usual holes around the top of the rim to attach a hat, wig, or headdress. There is a lack of staining around the top, where it seems that the wood was shaved to provide a better fit.

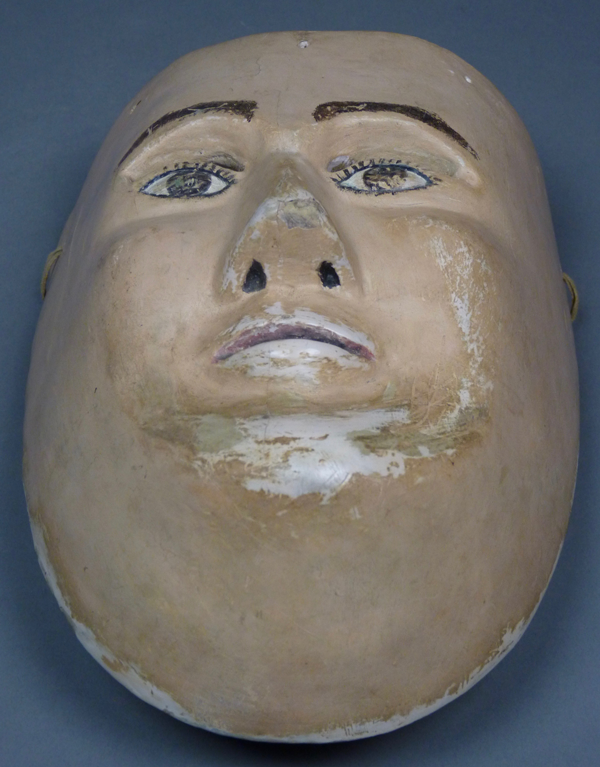

Finally, this is the Curpite mask that Dinah Gaston purchased directly from Alejandro Sánchez Mercado Senior in the late 1990s. In Zacán the Curpites masks lack not only ears but also mustaches. Esser shows this in a 1975 photo (Esser 1984, page 85, Figure 17). If we didn’t know better, we could easily mistake this mask as one of Maringuilla, although it does lack a cupid’s mouth. Dinah sold me this mask in 2000.

Look at the wear on this face! The eyes are carved.

There are drilled holes around the top of the rim for the attachment of the typical headdress/wig of horse or cow tails.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 3¼ inches deep.

The back of this mask is heavily stained from use.

Dinah Gaston had also collected this older Tarépiti mask from Zacán that was probably made by another carver. Someone has repainted it to serve as a Negrito mask. I believe that it was originally meant to be portray Grandfather because Esser (1984, page 85, Figure 17) included a photo of Tarépiti wearing a mask with the same goatee. Esser also stated that the Blackman dance in Zacán had been discontinued in the 1940s due to the Paracutin volcano, which had actually destroyed San Juan Parangaricutiro and caused some damage and flight in Zacán. This mask may have been recycled for service in some other town.

The green eyes are definitely a strange alteration.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6¼ inches wide, and 4½ inches deep.

There is dramatic staining on the back of this mask, as if it dates to the 1940s or 50s.

The next mask came to me with no provenance. I bought it because it I thought it looked a little like me. I am including it to illustrate the variety one discovers in the appearance of Curpite masks.

This mask lacks relief carved ears and the mustache is carved in shallow relief.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The back has been coated with an unknown substance such as varnish, probably to protect the wood from insect infestation. The coating makes it difficult to assess the degree of staining from use. It is probably fairly old.

I got the next mask from Sergio Roman Rodríguez of Mexico City in 1998. It was identified as a Viejo from Patzcuaro, Michoacán. This could be a Curpite/Viejo, but it is not from the Patzcuaro dance tradition, where classical Viejitos are the norm. It was probably brought there from some other town (we will look at the Viejito masks in a few weeks). In the Purépecha Masks: 2002 Catalogue (pp. 54-55), there are Viejito masks that look like this one; they come from Acachuén. According to Janet Brody Esser (Máscaras Ceremoniales …, 1984), there were Viejo masks with this general design in Ocumicho (p. 100) and Tanaquillo (p. 106) in 1975. However current YouTube™ videos suggest that the classic Viejito masks have been adopted in Ocumicho while one finds great variety in Tanaquillo. This is an old mask that could easily date to the 1960s or 70s. I am calling it a Curpite/Viejo.

This mask was carefully carved. I particularly like the shape of the eyes, which are unusual and highly refined.

This mask has the happy and enthusiastic expression that one associates with the Curpites. The ears have a stylized shape.

This is a fancy hairdo.

This mask is 9 inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

With such a worn back, this certainly appears to be an old mask.

Although the next mask came without provenance, it is obviously in the style of Victoriano Salgado of Uruapan, Michoacán, and it appears to be a mask intended to be worn by Tarépiti, or Grandfather.

I bought this mask on EBay, spots and all. I don’t know why the paint is spotted in this manner. I bought it anyway, because I was delighted to discover a Grandfather mask by this well-known carver.

This mask is 11½ inches tall, 7 inches wide, and 4¼ inches deep.

The back appears to be stained, but I have no idea whether it has been danced.

Next week I will turn to a discussion of the Blackman/Negrito masks.

Beautiful selection of masks. Thanks, john

Thank you John.

Bryan