As I had explained in my post of September 18, 2017, the Viejitos dance is an alternate form of the Danza de los Viejos, or Curpites. The Viejitos portray “little old men”, with wide grins, stooping posture, and walking sticks. Paradoxically, boys often perform in this role, portraying these elders with considerable energy. Maringuilla also dances with the Viejitos. These figures dance in apposition to the Ugly Maringuilla and the Viejitos Feos, the “uglies.”

Because I will be showing several masks from Turícuaro, Michoacán, I will begin with a Youtube ™ video of Viejitos from that town. In the middle section Maringuilla dances. The photographic quality of this video is only fair, but the performance is so much more authentic than many others on the internet that are being performed by folkloric companies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xN0bq6wRb9o

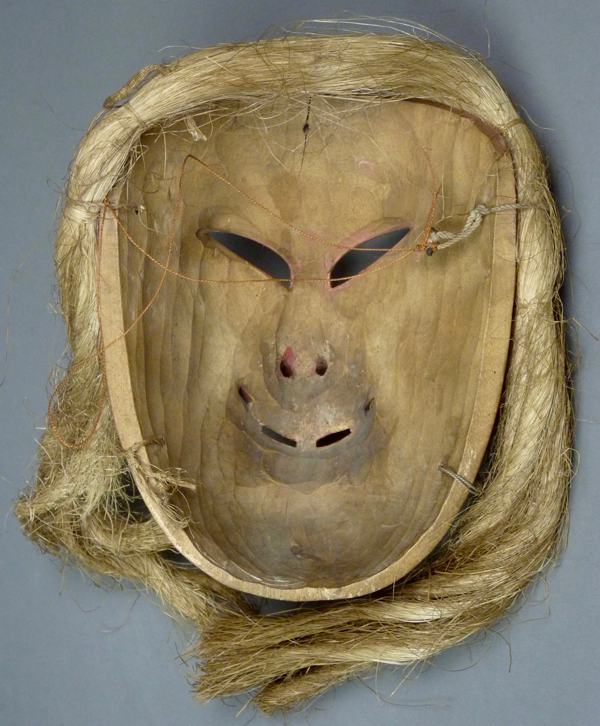

Today’s first mask was collected in Michoacán by Dinah Gaston. I purchased it from her in 2000.

Janet Brody Esser included a photo of a nearly identical mask in her 1984 book, Máscaras Ceremoniales de los Tarascos de la Sierra de Michoacán (page 109, figura 32.) Esser stated that the mask in her book was carved by José María Ponce of “Torícuaro,” [Turícuaro] Michoacán, in about 1970, she took this dance photo in Patzcuaro on July 8, 1971, and the dancer wearing this mask was from Janitzio, Michoacán, an island in Lake Patzcuaro. Turícuaro is about 50 miles to the west of Janitzio, demonstrating how these masks travel. The Ponce mask has virtually identical features to this one from Dinah Gaston, including the hair, eyes, nose, cheeks, mouth, and chin. Therefore I am attributing this first mask to José María Ponce of Turícuaro. Isn’t it splendid!

A feature that appears to identify Ponce are these long, thin, and slanted eyes.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6¼ inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back of this mask shows significant staining from use.

I bought the next mask from Vernon Kostohryz in 2009. It had been collected several years earlier by Carlos Moreno Vásquez in Michoacán. I immediately noticed that it had the same eyes as the Ponce masks, and I attributed it to José María Ponce of Turícuaro. I am including it here with a series of masks that may have been carved by Ponce. It was said to be a Moro, but at present those dancers usually don’t wear masks in Michoacán, although they may have in the past; the evidence for this is scant. On pages 35 and 44 of Purépecha Masks: 2002 Catalogue there is reference to Mask #8, a Chele or “Ugly Old Man” (feo) mask. Although his primary performance is in the Danza de los Cheles in Sevina, Michoacán, “this character also participates in the Moors dance.” That mask has long white hair and a white beard.

It is possible that this is a Corcovi mask, as those masks have dark hair and frowning mouths. The Corcovis dance with the Viejitos in several towns such as Charapan (Purépecha Masks: 2002 Catalogue, page 64). I will write about Corcovi masks in several weeks.

According to Purépecha Masks: 2002 Catalogue (pages 35-Item 6 and 44-Item 6), Turícuaro has a history of unique innovations in its Pastorela (Shepherd’s Play) performance. Three Kings have been included in the cast, one with a pink face and a white beard, a second with a gold beard, and the third king has a dark complexion. There are also three masked Tata Keri figures (elders) who,”on the days preceding December 24th invite the <<Principals>> of the community to join that year’s <<carguero>> in the celebration of the Pastorela… These are characters that inspire lots of respect” (a carguero is a ceremonial sponsor). A mask photo on page 44 illustrates a more recent Tata Keri mask that was carved by Rogelio Valencia Valdés of Turícuaro. It has a pink complexion, relief carved ears, a mustache and beard, and a frowning mouth, but the hair of that mask is painted gold. A King mask with golden hair by the same carver has a benevolent smile and lacks carved ears. So, it seems possible that this mask could depict Tata Keri.

This mask could easily be 50 years old. It is a terrific mask. Just look at the wonderful stylized ears!

One can find so much to like about this mask—the carving of the hair, the brows and the mustache, the shaping of the ears, and of course the eyes and the vision slits.

There is such a contrast between the frontal appearance of the ears and their appearance from the side.

The back edge of the beard has been chipped.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 7½ inches wide, and 4¼ inches deep.

This is a mid-20th century mask, with marked staining from use.

The next two masks are virtually identical. I bought them together from René Bustamante in 1994, as Viejitos from Tocuaro, Michoacán, one of the towns near Patzcuaro. The first is yet another mask that has eyes like those on the masks of José María Ponce, and the rest of the mask is also consistent with that attribution. As we saw with Esser’s Viejito by Ponce, the distance between Turícuaro and Patzcuaro is not enough to prevent the migration of masks from one of these towns to the other.

The vision slits on both masks have been enlarged, probably by the mask’s users, and not with the care evident in the initial carving.

Underneath the pink surface, this mask had previously had a tan complexion.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

This is an old, heavily worn mask. There is evidence of old infestation with boring insects.

The next mask differs from the last in two obvious respects. It has a rather well carved replacement nose that is markedly stained from use. The vision slits, which were initially rather small, have been even more crudely enlarged than those on the previous mask. But by now we know what Ponce’s eyes and vision slits look like when freshly carved.

So one can still recognize the typical Ponce eyes. There is a layer of tan paint under the pink on this mask as well.

Viewed from the side, one can see that the vision slits extended to become extremely thin at their outer ends. Probably they were wider at their medial ends, but still so slender that they limited a dancer’s vision. The carefully carved eyes were mutilated to solve this problem. There must be some other reason, as yet unknown, to explain the replacement nose and its lack of paint.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

Again we find evidence of old infestation. Maybe the original nose was damaged by wood-boring insects.

And now for an obvious change of carvers, this Viejito is typical of those carved by Victoriano Salgado Morales of Uruapan, Michoacán. I photographed it from the collection of my friend Gary Collison. Isn’t this a brilliant carving?

What a beautiful mask. Victoriano is a great living master.

The next mask is one of Maringuilla. I purchased it from the Gary Collison estate in 2008, as a mask from Michoacán. Looking in the Máscaras Purépechas: Catálogo 2002 (page 22, #51, or page 55, #51 in the English edition), I saw a similar mask that was made by Gregorio Trinidad Marcos of Acachuén, Michoacán. On page 65 there is a dance photo of a Maringuilla from Zopoco who is wearing this style of mask.

A YouTube video from Acachuén in 2013 includes such a mask at the very beginning, the one on the left. Then watch closely for a comical moment when a second Maringuilla, wearing a mask with a different face, roughly shoves a Feo aside.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yNPnpnz3kJU

Here is that Maringuilla mask from the Collison collection.

Notable are her relief carved spit curls. This mask came with a simple wig of braids and ribbons. Such wigs are not uncommonly found on the Maringuilla masks that dance with the Viejitos.

Her ears are pierced but she has lost her earrings.

Her nose is scuffed from normal use.

This mask is 8¼ inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

Cotton has been glued on the back of the forehead to make the mask more comfortable. There is moderate staining from use.

Next week we will examine other Viejito masks of different designs.