La Danza de Los Moros y Cristianos (the Moors and Christians dance) is popular in Mexico, having been introduced there by the Spanish shortly after their conquest of this region. There is a variation of this dance drama that is called La Danza de Los Santiagueros, and it can sometimes be difficult to tell them apart. The introduction of the Moors and Christians dance by the missionaries was clearly meant to impress the Indians of New Spain with the power of the Spanish conquerors, which was said to be based on their close relationship with the Christian God. In my view, the Indians of Mexico subtly transformed the Moors and Christians dance and the Santiagueros dance to serve their rather different purpose, which was apparently to covertly appeal to God for rescue from the Spanish, who abused them. I wrote about this in detail in my book—Mexican Masks and Puppets: Master Carvers of the Sierra de Puebla. Briefly, in the Indian version of these dances the Moors (the “bad” guys) secretly represent the Spanish, the Christians secretly represent the Indians, and a third group pretend to be allied with the Moors but are secretly allied with the Indians. I tell you this because in a video that follows the first photo, there is evidence of such an arrangement in San Pablo Tejalpa,

In el Estado de Mexico (the State of Mexico, the state with Mexico City at its center), the Christians are often led by a Santiago figure wearing a wooden horse or part of one at waist level, similar to what we find in the Santiagueros dance. A notable difference is that the Santiaguero dancers often wear masks, while their Christian counterparts often wear costumes without masks. Santiago himself seldom wears a mask in either dance.

Today we will begin with Moro masks used in the Moros y Cristianos dance from San Pablo Tejalpa, a town in the Municipio of Zumpahuacán, in el Estado de Mexico. There is a good dance photo of these dancers in Moya Rubio’s book, Máscaras: la otra cara de méxico/ Masks: The Other Face of Mexico, third (bilingual) edition (1986, p. 105) and another of the mask and headdress worn by the Moro dancers, this one with an articulated jaw (p.106). That author took those undated photos in San Felipe Tejalpa, which is evidently a very small town near San Pablo; I can’t find it on a map. However in the text (p.121), Moya Rubio stated that these masks were from San Pablo Tejalpa.

I bought this first mask and headdress from René Bustamante in 1994. It was said to be from San Augustin, Estado de Mexico, but I believe it was actually made in San Pablo Tejalpa. It probably dates to the 1970s.

The “lunar” headdress, made of paper mache over a reed frame, is a symbolic representation of the new moon, a Moorish image.

Here is a Youtube™ video of the Moros y Cristianos dance in San Pablo Tejalpa, from 2010. The dancers with masks like this one, and with similar “lunar” crowns, are the Moros or Moors, while Santiago and the Christians are without masks and wear the hats of Caveliers (think of the Three Musketeers), borrowed from Mexican cowboys. They also wear sky blue capes. There is a third group of dancers wearing black masks and various colored jackets. I have not learned their name or role (let’s call them Blackamoors); these dancers cross swords with Santiago and his unmasked assistants, but are they Moors? Watch particularly at 2:30 (two minutes and 30 seconds) as one of the Blackamoors carries a child Christian on his back, either to abduct or to protect him. A child Christian in the Danza de los Santiagueros is said to represent Santiago’s son, “Callintsin.” I suppose the same character might occur in the Moros y Cristianos dance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7YmYhvqGrU

As is evident from this side view, these Moors have highly exaggerated features. Their headdresses are decorated with colored foil. This mask is 9 inches tall (35 inches including the headdress), 7½ inches wide (the headdress is 27 inches wide), and 8 inches deep.

The back is stained from use. Wires bind the headdress to the mask, but originally these elements were tied together with twine.

I found a second video of dancers wearing white faced masks with other faces, but with similar lunar helmets, from San Bartolomé Atlatlahuca, which is just 30 miles north of San Pablo Tejalpa. I was intrigued to find a second helmet style there: I will call them “Comets.” The Christians there (except for Santaigo) wear masks. Mysteriously, the Comets and the Lunar dancers carry Mexican flags, as if they are allies, but the Comets cross swords with both the Lunar dancers and the Christians, as if they are allied with neither. Probably the comets are secretly the allies of the Christians (the Indians).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOeMymFonKk

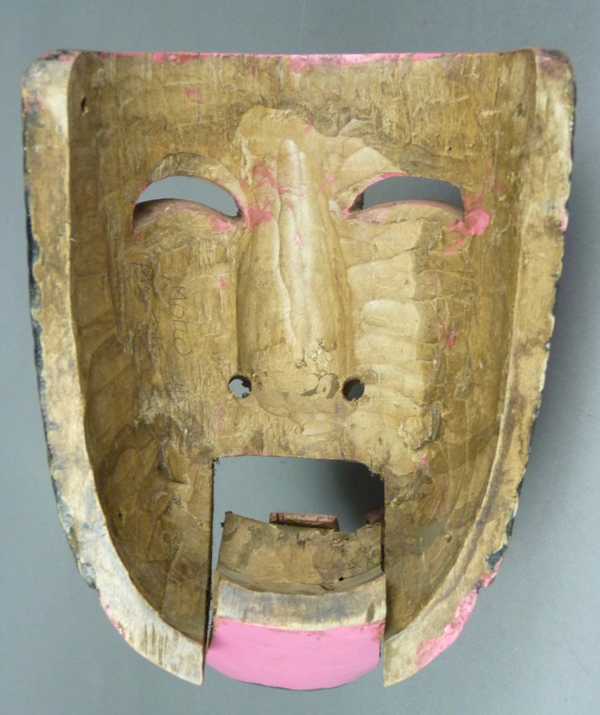

I bought another of these San Pablo Tejalpa Moor masks from Kelly Mecheling in 1995. This one has an articulated jaw, like the one in Moya Rubio’s collection, but it came without its headdress. Kelly had obtained this mask from Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazón.

After Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, I unsuccessfully attempted to learn whether Kelly Mecheling and his wife were ok. If any reader has current contact information for Kelly, I would appreciate receiving this. In 1995 he had a gallery in New Orleans—Trade Gallery.

Here is the articulated jaw Moro mask from Jaled and Estela by way of Kelly.

Here the mouth is nearly closed. The paint on the left eye has been worn away.

Here the mouth is open wide.

The features are exaggerated, just as on the other mask.

In this photo the mouth is again wide open. This mask is 7½ inches tall (9 inches with the jaw open), 6 inches wide, and 7½ inches deep.

The back is heavily stained. In fact, this is an excellent example of differential staining, in which the rim of the back is more darkly stained because of greater skin contact there.

Here is one last shot with open mouth.

Next week I will continue to show you Moro masks from the State of Mexico.

Bryan Stevens

I inherited a collection of masks that are really old. Frankly, I don’t know much about them as I wasn’t aware I was going to get them or I would have asked. In any regard, the collection has about 20 pieces including 2 life-sized skeletons and I’m looking to sell them – hopefully to someone who knows what they are and will respectfully display them. Additionally, there’s also pottery and textiles and embroidery pieces, as well as beautiful bags and ponchos.

I live in Palm Springs and would love some advice on where to sell them. I was going to take them to a high-end consignment outlet today until I ran across your website. Now that I know what they are, I think I’m glad I waited.

So any advice you could provide would be hugely appreciated.

Thank you