Another carver included in Jim Griffith’s study (see last week’s post) was “Francisco Parras,” although the author did not include any photos of masks by that artist. One more often sees this man’s name rendered as “Pancho” Parra. He was an excellent and prolific mascarero for many years, and his Pascola masks are heavily represented in several important collections. Pancho has lived in various towns in Sonora, including Salitrál, a rancho in the Municipio of Alamos, El Retiro, El Rodeo, and Wirachaka. I bought my first mask by Pancho from Robin and Barbara Cleaver in 1988. It had been brought up from Sonora by Roberto Ruiz with little provenance. I owned it for years before discovering the name of the carver by comparing it to masks in some of those other collections. I just discovered that I probably have a second Pancho Parra mask, having long thought it was by someone else. Had I the opportunity, I would have bought many more masks by this carver, because I really admire his artistry. Fortunately I have permission to include many photos of additional examples from another collection.

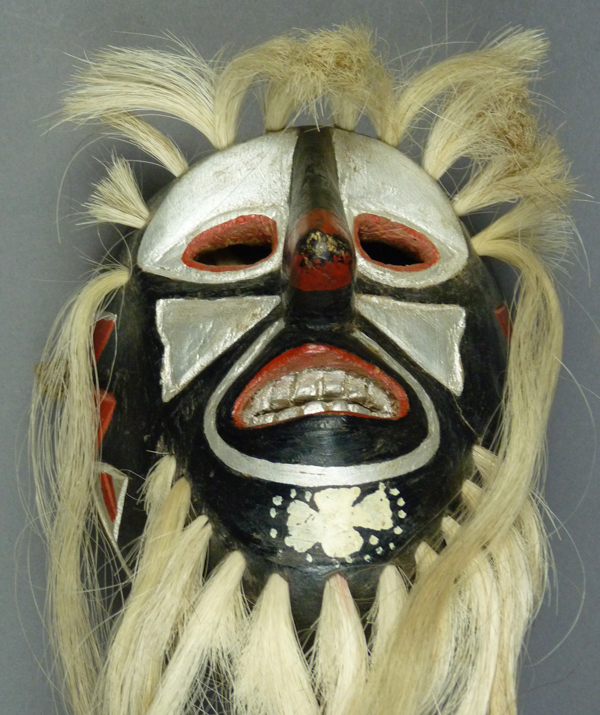

Rio Mayo Pascola masks usually lack the carved and/or painted white triangles under the eyes that we find on Yaqui Pascola masks. Instead we often see designs flanking the nose, oval in this instance. The red lips on this mask were apparently painted with nail polish.

An essential step in the recognition of a mask by Pancho Parra is to examine the design details of the meeting of the top of the nose with the forehead. No two masks are exactly the same, but there is a consistent arrangement across Pancho’s masks—that the top of the nose comes to a point at the level of the plateau of the forehead, and that tapered top end of the nose also conforms to the slanted areas of the brows on both sides. Please study the photos above and below this caption to see what I mean. This can be thought of as Pancho’s signature.

Next is a photo of the pointed top of the nose, which more or less meets the top of the mask.

As you will see in various photos, this mask was enhanced by the addition of a number of glass or plastic “jewels.”

The rim design is discontinuous, a feature often seen on Rio Mayo Pascola masks.

Here are those jewels, arranged in a disc shaped pattern around the forehead cross. The cross represents the sun, its light shining in the four cardinal directions, while the jewels might also represent light, or flowers.

The chin view provides another perspective on the meeting of the top of the nose with the carved brows of the mask.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 5¾ inches wide, and 3¾ inches deep.

We see moderate staining from use around the border of the mask, but deeper color within, suggesting that this was a heavily stained back that was cleaned to make it look more presentable for sale.

The second mask in today’s post came to me in 1998 as an alleged mask by Alfredo Lopez. It had been collected in Bacobampo, Sonora from Alfredo’s son, who dated it to 1980 or earlier. He had danced with this mask until 1995. In my preparations for this post, I was struck by the resemblance of this “Alfredo mask” to those of Pancho Parra; the nose is particularly characteristic. I consulted Tom Kolaz, who also recognized it as likely to be Pancho Parra’s work. So now I probably have two masks by this carver. Why the emphasis on “probably,” you might wonder. The question is not entirely resolved because the history may be slightly garbled. What if Alfredo Lopez was the son of the carver and the actual carver was another well known artist, Sylvestre Lopez, who lived and worked in Bacobampo? According to Tom Kolaz, Sylvestre’s masks sometimes resemble those of Pancho Parra. So really this mask could either be by Pancho or Sylvestre. Either way, its a very nice mask.

This one has a drilled hole on the left side of the mouth, perhaps for a cigarette.

This mask has the typical Pancho Parra junction of the top of the nose and the forehead. The shape of the nose is also characteristic, and hardly different from the one on the first mask.

The forehead cross is enclosed in a beautiful jeweled arch, constructed of small silver triangles, and the same triangles form the rim design. Those triangles all probably represent rays of light. Although this is not so obvious from the photo, there are some extra openings on the left side of the forehead, which reveal hollow spaces under the surface. These resulted from an infestation with wood boring insects. These are long gone, but their ravages remain. It is wonderful that the surface of this mask remains so intact.

This view from below the chin reveals the classic tapering of a Pancho Parra nose to a point. One also notices the stylized relief carved rims around the eyes. Another hole from the former insect infestation can be seen on the right side of the chin. The bare spot on the nose is unrelated to insects; it is a scrape mark. The nose and chin of a mask are particularly vulnerable to damage like this.

This close-up photo reveals the top of the nose in greater detail. This mask is 7¼ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3¼ inches deep.

The back is nicely stained from long use. Someone wrote the name, Alfredo Lopez, on the back of the mask, along with the name of his town, Bacobampo, Sonora, recording the history provided by the dancer. But examination and experience have suggested other histories.

For comparison, I will show photos of three additional masks by Pancho Parra from the collection of Jerry Collings, of Silver City, New Mexico. In 2011 Jerry kindly allowed me to photograph his collection for future publication. It is my understanding that he may have later traded these masks to Gallery West, in Tucson, Arizona.

Our third example, collected by Edmond Faubert in 1987, was said to have been carved by Pancho c. 1965-70.

Here we see another typical Rio Mayo cheek design, flanking the nose.

The top of the nose does not come quite so close to the edge of the top as the usual Pancho mask. Thumb tacks decorate the rim design and the forehead cross.

This mask is 7 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The back is darkly stained after such long use. There are stable cracks.

Today’s fourth mask was collected by Roberto Ruiz for Edmond Faubert in Guayparin, Sonora in 1983. It was said to have been carved by Pancho Parra and danced for three years, so it dates to 1980. I now believe that it was actually carved by Bonifacio Baumea Sauzemea, who lived and worked in Guayparin at that time, and whose masks are frequently confused with those of Pancho Parra. I plan to focus on Bonifacio’s Pascola masks in several weeks, but now that I have erroneously included this one in today’s post, I will compare it to the masks of Pancho Parra to demonstrate these carvers’ sometimes subtle differences.

On this example, the cheek designs flanking the nose are chevron shaped, a feature commonly found on the masks of Pancho and Bonifacio. The rim design, of triangles strung on a slender incised line, is typical of Bonifacio’s masks. Pancho Parra has used this form for his rim design on some occasions, but his anchoring line is usually broader or bolder. Another subtle distinguishing detail is seen in the front and side views—Bonifacio tended to separate the borders surrounding the eyes from the space above those rims, either by relief carving of the rims or by the use of contrasting paint. Sometimes (as in this example, although this is difficult to see), it is the space above that bulges, having been carved in relief, while the rim of the eye is often flat. Pancho usually managed these design elements more casually.

This nose has more of a curve than the three that you have already seen, and this variant profile is also used by both carvers, although Pancho probably did this less often and Bonifacio more.

Silver paint dominates the color palette, a more common feature on Bonifacio’s masks, but often found on Pancho’s.

There is a chin cross on this mask, in a different color than the other design elements, and therefor a later addition. Neither Pancho nor Bonifacio routinely included a chin cross. The subtle detail that is only clearly seen in this view is that the nose does not taper much in width as it goes up; it is nearly as wide at the base as at the top, although this is not so obvious. Instead of gradually thinning, so that it comes to a point (as Pancho’s noses routinely do), this nose is gradually reduced in its depth, tapering to a sliver as it meets the top rim of the mask. This is more consistent with Bonifacio’s style.

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

The back of this mask is moderately stained.

The tag on the last mask, which you will see in a later photograph- states this mask was “made in 1952 by Pancho Parra at Wirachaka, municipio Navajoa, Sonora.” So it is now 66 years old. It was collected from Librido Leyva of Los Zapotes.

The nose on this mask curves like that on the fourth mask, but the top resembles its counterpart on the first mask, tapered and pointed. This is a classic Pancho Parra mask.

This is another Rio Mayo mask with a discontinuous rim design. Pancho often laves a gap between the two styles, as we see here.

There are inlaid designs flanking the cross; is this glass?

This mask is 7½ inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

Of course this old mask has a heavily stained back.

Next week we will examine four more Pancho Parra masks from the same private collection as the last three.

Bryan Stevens