In his Master’s Thesis of 1967, James Griffith told of his difficulty collecting masks by a very popular Rio Mayo carver, Sylvestre Lopez. Dancers were reluctant to sell masks that had been carved by Sylvestre, even if they owned other masks as well, because Sylvestre’s masks were invariably their favorites. In desperation, Griffith ordered two new masks from the carver, but it seemed that Sylvestre was too busy to fill this order in the period when the writer was in the area. In one instance Griffith was able to buy a danced mask by Sylvestre, but this was because the dancer had died and Griffith bought it from the widow; he was sold two others that had imperfections! He commented on the reasons Silvestre was so busy. Most importantly, Sylvestre was “also a Curandero, or healing expert, and often practices up in the Yaqui country at Vicam.” Silvestre had even obtained a Yaqui Pascola mask in Vicam. His curing services there were apparently in great demand. He performed in Rio Mayo fiestas as a Deer Singer, and in addition to supplying masks for the Pascola dancers, “he also makes rasps for the Deer Singers, and has made at least one head for the Deer Dancer” (pp. 101-102).

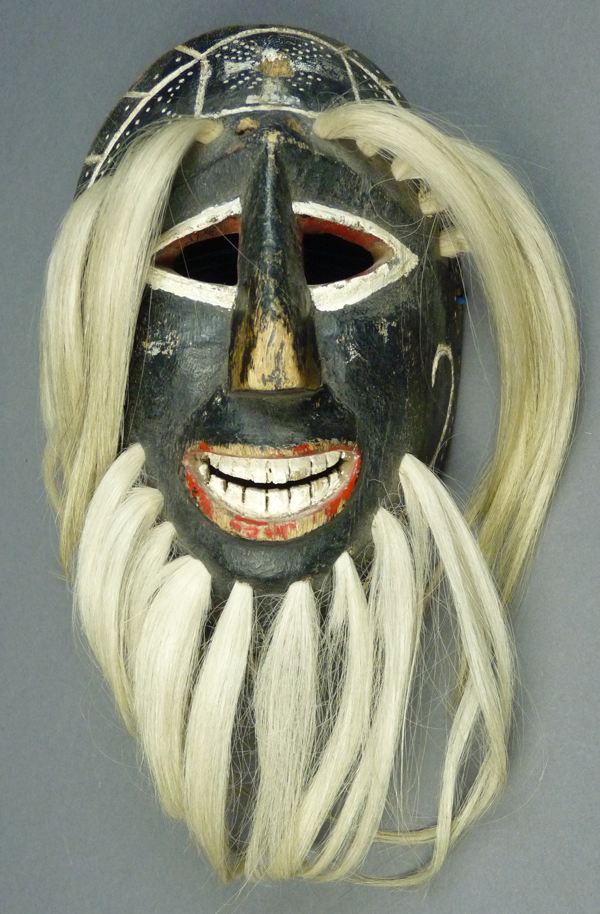

I have no mask in my collection by Sylvestre, but I can show two masks that I had photographed in 2011, when they were in the collection of Jerry Collings. Both had been attributed to Sylvestre at the time of original collection. I will start with this one, which was collected from Librido Leyva of El Zapote, Sonora at an unknown date. It was thought to have been carved in Borabampo, Sonora circa 1950.

I had provided a link to Griffith’s Master’s Thesis document in an earlier post and I will repeat it here, so that you can see photos of 9 masks by Sylvestre (M13, M14, M15, P9, P10, P16, P17, P19, and P20) that were provided in that document (pp. 50, 51, 54, and 55). Please left click on this link, and the document may simply open. If not, scroll down on the page that opens, and left click on the “download” button that appears on the lower right.

https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/551909?show=full

When I compare these nine masks, they seem to present a variety of features, and some resemble masks by other Rio Mayo carvers, such as the Alameas. Furthermore, as you might notice in the opening photo, they seem more tall and narrow (like Yaqui masks), in comparison to the ordinarily more oval Mayo masks. Griffith also commented on this variety—”The impression left by this man’s work is one of diversity within the accepted Rio Mayo range, with a tendency towards older items (the use of life forms and flattened faces) and a similar tendency towards more ornate forms.” He also implied that Sylvestre’s flexibility of designs served the varying tastes of several generations of Pascola dancers, younger and older, and that Sylvestre apparently felt free to combine traditional elements with others that were more innovative.

Here is a link to mask M15 (the Arizona State Museum acquisition number is 2005-809-15) in Griffith’s document. Please note M14 (2005-209-14), the second from the left in the row above the enlarged photo, and if you click on that image it will be enlarged instead of M15. M14 is a good example of a mask that was attributed to Sylvestre, and hopefully correctly, but at first glance it resembles a mask by one of the Alameas. I photographed mask M14 at Jim Griffith’s house in 1990 and from those photos I can see that this is probably not an Alamea mask because it has a flat face. Another detail that is not so apparent from the frontal museum photo is that the upper lip of M14 juts out sharply from the face; this is dramatic carving.

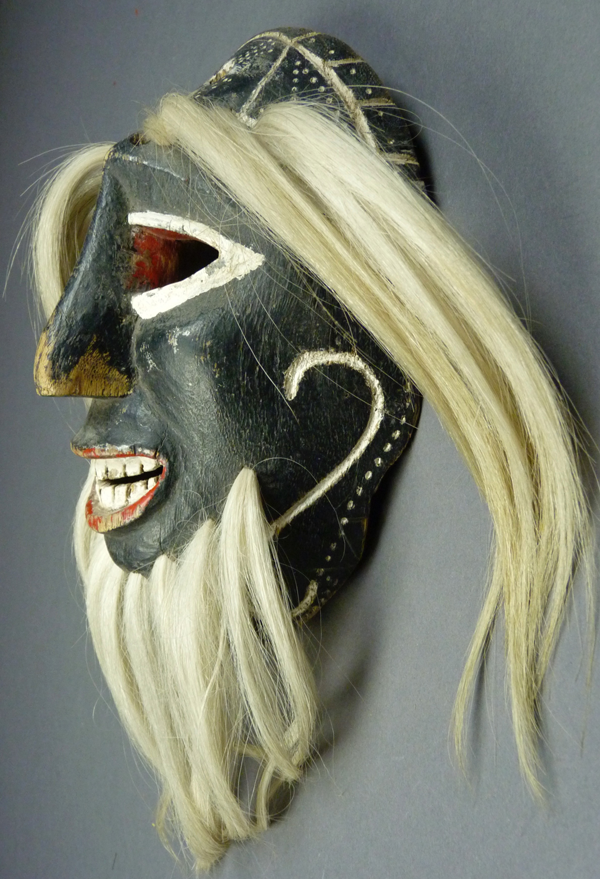

Here are more views of the opening mask that was said to date from about 1950.

I don’t think that this mask originally had a formal rim design. If it did, that design has been painted over with less formal elements. In marked contrast are the carefully carved wedges on the cheeks.

There is a carved forehead cross that resembles those used by many other carvers. Incidentally, Jim Griffith referred to this cross design as a “cross patée,” while I have chosen to call it a “Maltese cross.”

These are “triangular” eyes, like those we have already seen on masks by other carvers such as Bonifacio Balmea Sauzemea.

There is a carved chin cross, which may well have been an original feature on this mask.

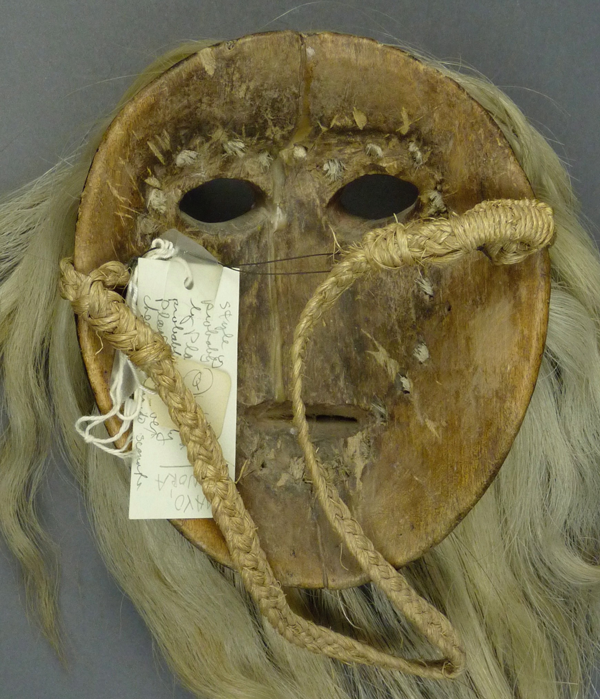

The back of this mask is dirty, stained, and battered from long use, while the leather strap is obviously a more recent addition. Please particularly note a feature which I believe to be a good marker for this carver—the way that the central carved depression is carefully extended to include the points of attachment of the hair bundles, which seem to reside in their own groove. We don’t find this groove on the masks of other Rio Mayo carvers such as the Alameas, Candelario, or Bonifacio, Brígido doesn’t tie in the back, and Pancho Parra has an inconsistent tendency to cut but not groove to that line.

Here is the second mask by Sylvestre that I photographed in the collection of Jerry Collings.

There are triangular eyes, a similar mouth, but the nose has a different profile.

In this side view, one can observe that Sylvestre sometimes carved convex cheeks on his mask. This is a feature that I had associated with the Alameas, but Griffith pointed out that Sylvestre also used this feature, although not consistently. The carved S shaped design on the cheeks is not a typical Rio Mayo feature, but it is commonly used by Yaqui carvers, reminding us that Sylvestre had considerable contact with Yaqui Pascola mask traditions from his frequent curing trips to Vicam, Sonora. On the other hand, this mask has a spotted rim design around the top like the one favored by Bonifacio (a Rio Mayo carver), but connected to a curving line of spots which resembles an older “pecked” style that I associate with Mayo carvers in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. As Griffith said, Sylvestre mixes styles rather than sticking to one consistent model. I’m not complaining; I really like this mask.

The worn painted designs on the forehead are very attractive. There is a carefully painted cross in a style typically used by Alcario Camea, another traditional Rio Mayo carver who will be featured in a future post, along with artful dotted designs—rays of light around the cross and chevrons outlined in dots, flanking the cross. One begins to see why Sylvestre’s masks were so popular.

Here is that grooved area above the eyes again, apparently meant to accommodate the attachment of the eyebrow hair bundles.

Something that I hadn’t realized until I recently reread Griffith’s descriptions of Sylvestre’s masks was that this carver sometimes made Pascola masks with convex cheeks like the ones on the last mask. I thought back to one of the masks in my post about Plácido Alamea, which others had attributed to Plácido, and I had accepted their attribution, particularly because the mask had convex cheeks. However I had also thought that it had an unusual nose for an Alamea mask. Now when I look again at the back of that mask I see the indented groove over the eyes that I had seen on the two masks from the Jerry Collings collection. I am going to include it again in this post so that you may consider the idea that it may really have been carved by Sylvestre Lopez.

Rio Mayo artisans carve triangular or chevron shaped wedges pointing towards the nose, while Yaquis favor triangular “tears” that drop down from the eyes. On this mask we find something in between those two styles, again suggesting a Yaqui influence (the spots lateral to the triangles are unusual on Yaqui or Mayo masks). A cross on the chin is another feature that is commonly seen on Yaqui Pascola masks and much less often found on Rio Mayo masks.

The eyes are almond shaped, with delicate edges carved in relief. I also admire this humped nose.

The next photo highlights that carefully carved chin cross, which has been distorted by a later crack in the wood.

This mask is 7¼ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

The creator of this mask carved that furrow above the eyes that cradles the string holding the ring of hair bundles, a groove like thise we observed on the other two masks.

I hope that you have enjoyed my introduction to this exciting and talented Mayo carver. Next week we will examine the masks of Alcario Camea.

Bryan Stevens