When James Griffith was collecting Pascola masks that had been created by Rio Mayo carvers, back in 1965, he found it particularly easy to build a representative collection of masks by one of the local carvers, Alcario Camea, but he had marked difficulty when he attempted to buy danced masks by Silvestre Lopez. As I noted in last week’s post, masks carved by Sylvestre were perceived as superior to most of the others in terms of desirable design features. In contrast, Alcario’s masks were carefully carved, and perhaps brilliant in their eccentricity, but these idiosyncratic design features apparently went in and out of fashion, over time. One might imagine that these shifts in taste reflect some degree of secularization of the Pascola’s role, but I don’t believe that there is much of a published literature in this area. However, Tom Kolaz has been particularly interested in tracking these changing Pascola mask fashions on the Rio Mayo, and I look forward to a time when he will make his observations more widely available.

In April 1995, I briefly owned an excellent mask by Alcario, with typical features. I immediately traded it for another mask that I coveted. I was later able to photograph this mask in 2011, after it had entered the collection of Jerry Collings. By now this mask has probably moved on to the collection of Gallery West, in Tucson Arizona. I have no photos of other masks by Alcario to offer you, apart from those in Griffith’s Masters Thesis of 1967, which you can access through the link that follows. Here is a photo of the mask that I briefly owned in 1995, to get us started. I had purchased that mask from Mark Bahti, of Tucson Arizona, who reported that his father, Tom Bahti had collected the mask several decades earlier. In other words, it probably dates to the same period as Jim Griffith’s research.

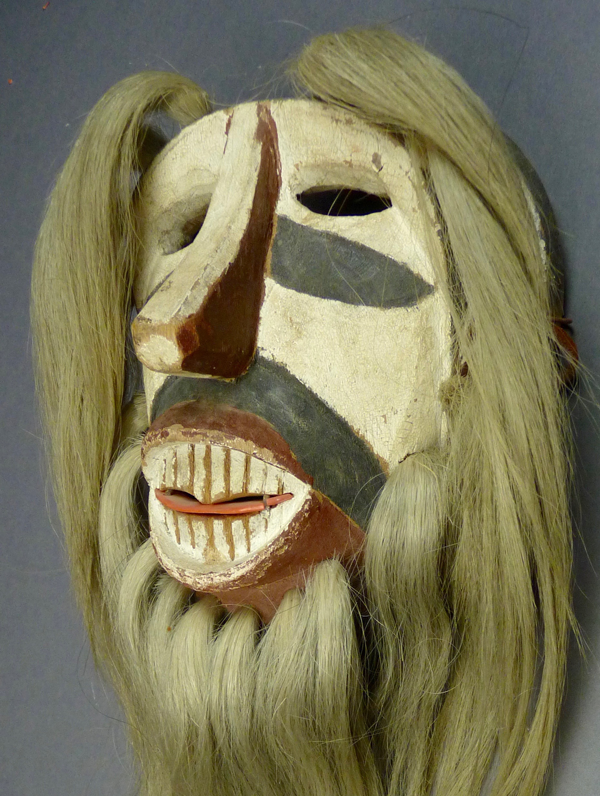

In the frontal view one sees a number of features that appear on almost every one of Alcario’s masks. These include:

1. the typical cross (which Griffith dubbed the “Alcario cross);

2. almond shaped eyes that are slanted downward at their outer corners;

3. oversized crescent shaped wedges under the eyes (almost as if a second mustache);

4. a broad drooping mustache between the bottom of the nose and the upper lip;

5. open teeth;

6. a ring of hair bundles around the face;

7. a slab-like nose with “ski-jump” contour and a blunt end.

8. and the use of boldly contrasting colors, noted Griffith.

Here is that link to James Griffith’s Masters Thesis on the subject of Rio Mayo Pascola masks, which appeared in 1967. There is a discussion devoted to Alcario and his masks (pp. 95-100), and photos of masks by Alcario (M6, M7, M8, M9, M10, and M11) in illustrations that follow page 48. Griffith commented about mask M6, “The face has been scraped down and painted black, leaving a slight ridge around it,” and probably eliminating many of these typical features in the process (page 100). It is not uncommon for a dancer to rework a mask to suit himself. In a more startling comment, Griffith said of mask M11 that ” the face is said to be that of a woman” (figure 12f after page 49). I doubt that Alcario made a Pascola mask with a woman’s face, but if so this would be a first, for me to have seen one, after I have looked at hundreds.

Also, here is a link to mask M11 (2005-809-11), the mask by Alcario that is said to represent a female.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/318629742362788606/

Here is a good view of the nose, which Griffith called “sway-backed,” probably a more professional term than my “ski-jump contour.”

On this example a plastic tongue has been inserted in the gap between the teeth, but this was probably a later addition by a dancer. Generally speaking, Alcario’s masks lack tongues, but nor do they usually have this beak-like bite.

We see an attractive rim design which includes a leaf-like form.

Here is a better view of that “Alcario cross.”

In contrast to the elaborate and formal forehead cross, there is no chin cross on Alcario’s masks.

This mask is 7 ¾ inches tall, 5¾ inches wide, and 4½ inches deep.

The back has moderate staining from use.

I hope that you enjoyed seeing such a vivid example of this carver’s work.

Next week we will examine the masks of Benito Moroyoki.

Bryan Stevens