In 2004 I purchased a Rio Mayo Pascola mask from Dinah Gaston that had snakes carved in relief on the face. Dinah had visited Leonardo Valdez in Etchojoa in June, 2000, and he had taken her to a fiesta. There she obtained this mask from the lead Pascola, Bartolo, who reported that he had danced with it for 15 years. According to Tom Kolaz, Bartolo Matus was not only the lead Pascola in Etchojoa at that time, but also he probably was the mask’s carver. Perhaps he was also the originator of this style’s use in the Rio Mayo villages, Tom speculated. He was so intrigued by this mask that he made further inquiries through contacts he had in that region, and ultimately he discovered additional masks there with relief carved snakes on their faces. I obtained one of these from Tom in 2006. In today’s post I will show you these two exciting masks.

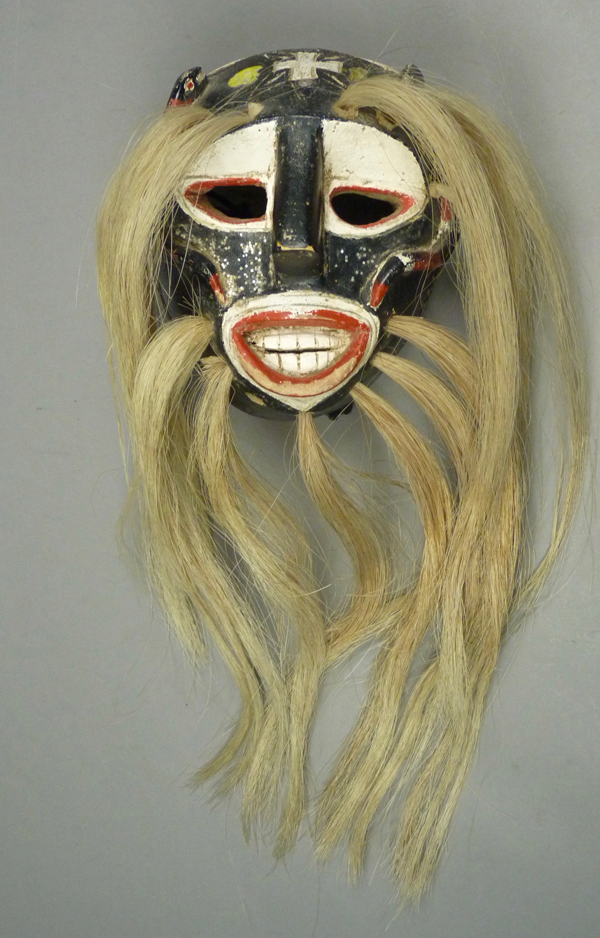

Here is the one that was collected by Dinah Gaston in 2000. It was said to date to c. 1985.

The snake bodies create the illusion of exaggerated cheekbones.

The snakes have tiny faces with painted features.

In this side view one can see the entire snake, which has been carved in relief in place (from the same block of wood).

The rim design is a version of one that has been used by other Rio Mayo carvers such as Bonifacio Balmea.

The forehead cross, more or less of the Maltese form that is common in this area, has been enhanced with rays of light, floral petals, and brightly colored sequins, reminding us that the cross on a Pascola’s mask is a syncretic design, which represents the Christian cross and the Sun.

I admire the elegance of the painted and inscribed ring around the mouth.

There is no evidence of a chin cross.

This mask is 6 ½ inches tall, 5 ½ inches wide, and 3 ½ inches deep.

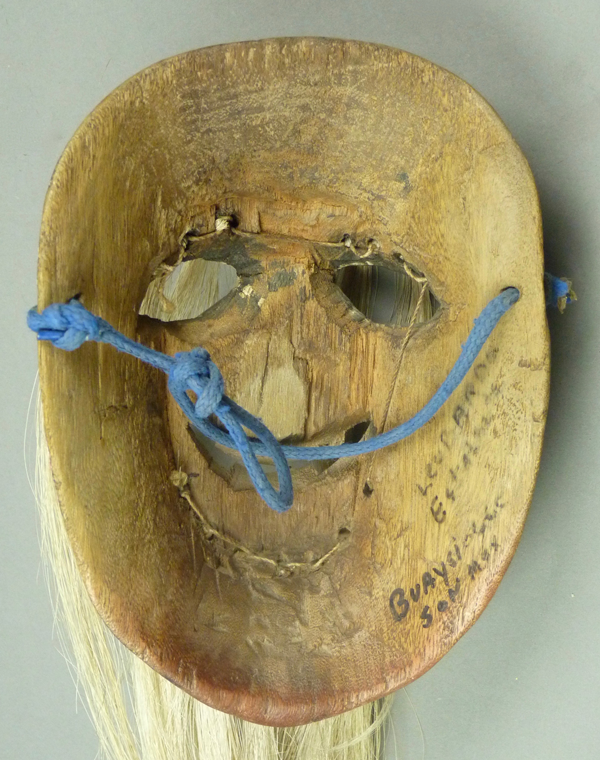

The back is obviously worn from use.

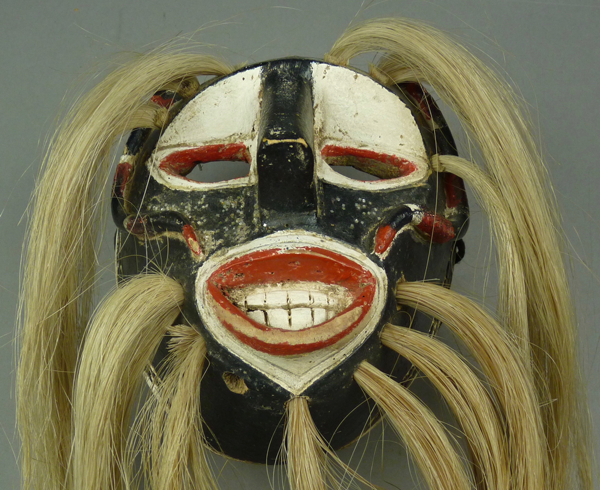

Here is the mask that I purchased from Tom Kolaz in 2006. More recently he shared photos of other Rio Mayo masks with snakes from a variety of carvers, leading me to think that such masks had become a fad among those Pascola dancers, although I believe they remained virtually unknown in the larger world until this post. In other words, such changing cultural features in Mexican masks can be driven by the wish to appeal to a broader and non-Indian audience, but such changes on the Rio Mayo appear to be driven by the dancers’ tastes.

Tom Kolaz has a very similar mask in his collection, virtually the same mask with different paint. He has been uncertain who carved these two masks (this one and his near duplicate).

In the previous photo, please note the elaborate detail of the painted features, and the interaction between the relief carved snakes and the adjacent painted elements, which mimic the appearance of snakeskin. There is even a painted snake crawling up the bridge of the nose.

This mask has an unusually prominent nose and an extreme grin that has been accentuated by the painted outline.

Here is the entire snake.

The forehead cross has been carefully painted.

There is no evidence of a chin cross. This rim design extends completely around the chin, and the tails of the two snakes nearly meet.

This mask is 7 inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

This mask was reportedly found in Guásimas/ Guaysímas, Sonora, a town north of Potam (a Yaqui town), but of course it is a Mayo mask from Southern Sonora. The back is stained from hard use.

Next week

Bryan Stevens