José Mopay appears to be a rare example of a Sinaloa Mayo carver whose work is attributed to the early 20th century, rather than the middle of the century or later. Although the names of such early carvers have been frequently forgotten in their communities, in this instance several masks in the collection of Barney Burns and Mahina Drees were said to be quite old, and two of these were said to have been carved by Mopay. All four of today’s masks share an unusual shape, and two share unusual and attractive designs flanking the forehead cross. So it is with great pleasure that I present these masks to you today, and I hope to hear of more examples in your collections.

There is another reason to find these masks exciting. Yaqui masks with goat faces do not appear to date earlier than the late 1930s, goat faced masks don’t seem to ever have been popular among the Mayo Indians of Sonora, but anthropologists such as Jim Griffith have wondered about the possibility that goat faced Pascola masks might have been used much earlier among the Sinaloa Mayo Indians. Mopay’s masks raise this question again.

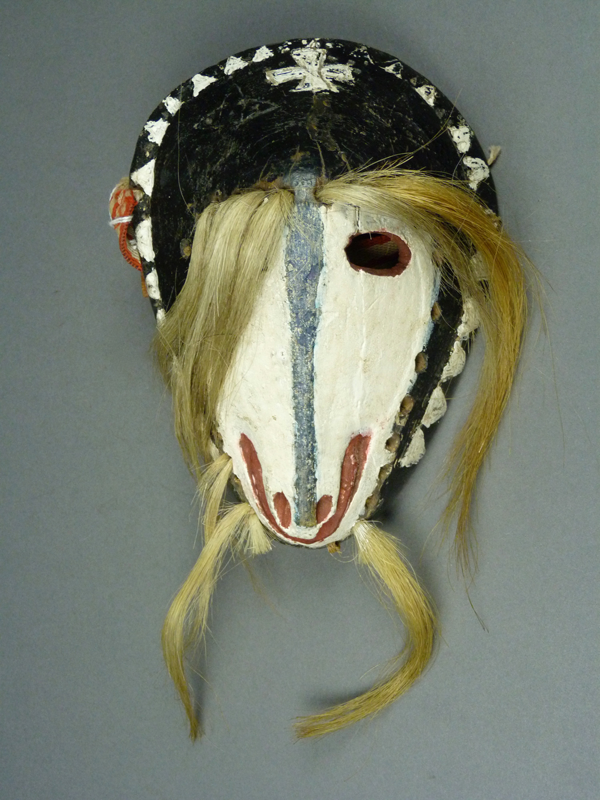

This mask, which was collected in March, 1991, was said to be 70 years old (as if made c. 1920). The carver was said to be José Mopay of Tenoque Viejo, Sinaloa. It has a dramatic tapering shape.

Many of the hair bundles have been lost, but the holes tell us that the hair for the brows and beard was applied in a continuous ring.

There are remarkable inscribed designs flanking the forehead cross. I believe that these represent stars, but I suppose that they could be flowers.

Stars or flowers?

The chin tapers dramatically.

There is barely room for the hair bundles at the bottom of this mask.

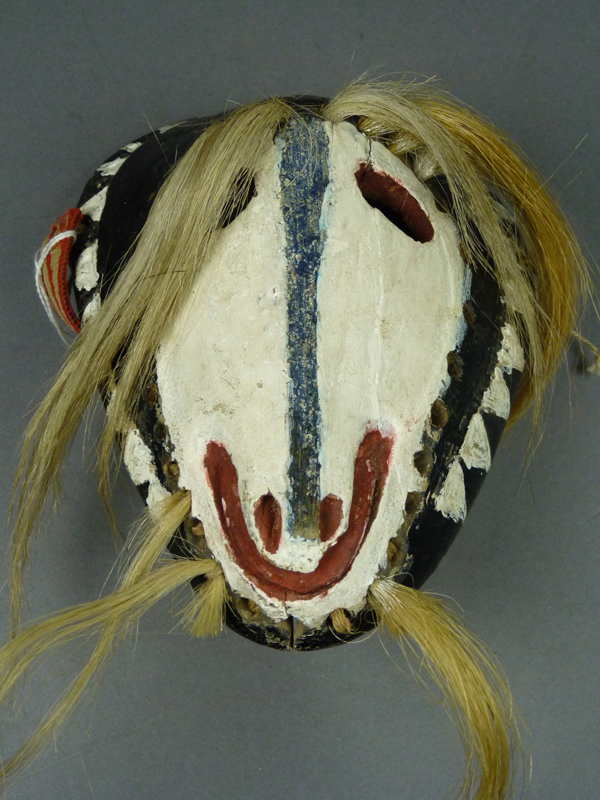

The back of this mask is very darkly stained. The ring of holes for the attachment of the hair bundles is easily seen on the back.

The next mask was collected in 1990, with no provenance. Tom Kolaz pointed out to me that it greatly resembles two masks by José Mopay or Topay in the Barney and Mahina collection. It has the same tapering shape as the first mask, the same forehead cross, and inscribed flowers flanking the cross. It is, of course, painted an unusual shade of green.

The ring of holes around this face is not continuous.

Also like the first mask, the hair bundles at the chin are at the edge of the chin.

Here is one of the inscribed flowers that flank the forehead cross.

Bright green paint.

The back is darkly stained.

The third mask was collected from Saturnino Valenzuela in 1990. A recent recopied label states that the Carver was José Topay of Tenoque Viejo, Sinaloa, +/_1930. However the collection information that was written by Mahina on the back reads “JM, 9/90, Mexico.” So this is another mask carved by José Mopay (not Topay).

This mask has the same cross as the other two, but flanking designs are not apparent. The cross has been decorated with what is probably an applied plastic flower.

The narrow nose makes this mask look like a dog, but it probably represents a goat. The brows on this mask do not form a ring with the hair of the beard. Rather, they are very narrow.

There is a hole at the top of the back through which the flower was attached.

The back of this mask is also very darkly stained.

The last mask in today’s post was estimated to date to about 1965. It has a different cross and lacks designs flanking the cross. The carver is not noted. One wonders whether this was made by someone in Mopay’s family, such as a son or grandson.

The paint (it was probably repainted) diverts one’s attention from the observation that this mask has the same overall tapering shape as the other three, although the nose is longer and less blunt on the end.

We do find a nearly continuous ring of hair around the face.

At the chin, the hair is again attached near the edge.

The back is heavily stained, but not as darkly as the other three, of course. The taper on the back is less extreme.

Next week we will look at another mask that resembles those of José Mopay.

Bryan Stevens