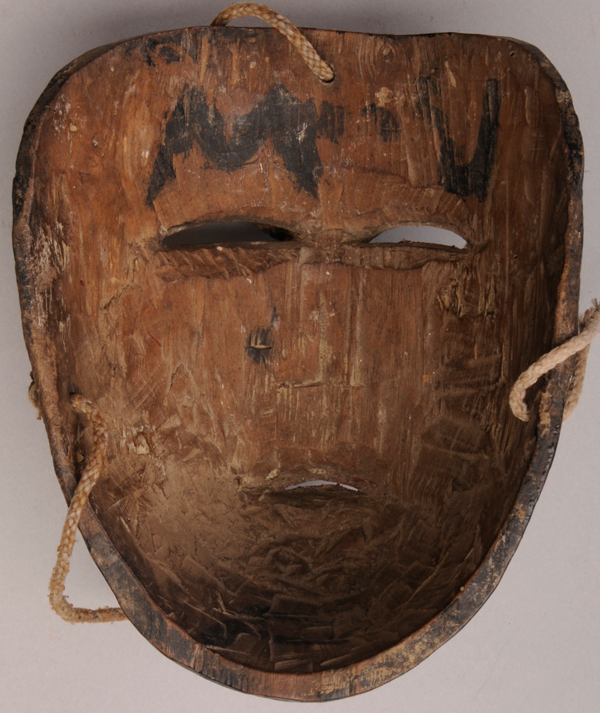

In anticipation of Christmas, I want to tell you about two dances associated with this season in the Sierra de Puebla, la Danza de Lakapíjkuyu and la Danza de Lakakgolo. Here is a mask from the Lakapíjkuyu dance.

This lovely old mask was carved by José González Galindo of Coxquihui, Veracruz in about 1980. In last week’s post, his son was the carver of the Mickey Mouse mask.

This mask is 6½ inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

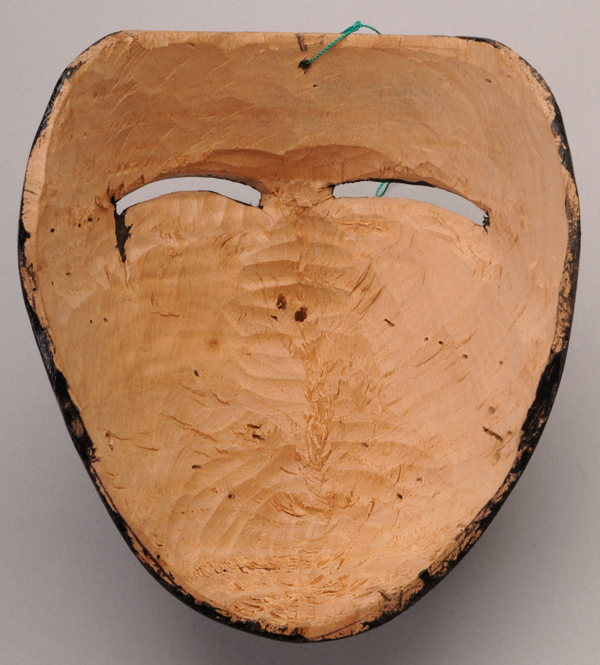

The back reveals that this mask has had heavy use over a period of many years.

Here is a photo that I took in December 2010 of José González Galindo, who carved this mask, and his son, José Gonzalez Diaz (the carver of the Mickey mouse mask).

In my post of September 8, 2014, regarding la Danza del Matarachín, I told you about a mysterious legend from the Sierra de Puebla that had been described by two Mexican anthropologists, Zeferino Gaona Vega and Facunda Juárez Hernández in their paper “La Danza de Lakapíjkuyu en las Posadas del Municipio de Coxquihui, Veracruz” (reprinted in Entre los Hombres y las Deidades: Las Danzas del Totonacapan, 2005, 134-139). Here is the legend. Until the birth of Jesus, the world was dark, but at the moment of his birth an extremely bright star appeared (this was actually the sun). There were people and animals who apparently understood that the light was a gift from this newborn baby, so they gathered around him. A second version of this story states that human visitors came dressed as animals, some to worship the infant, others to rob or kill him. Suddenly the sun rose. The myths don’t clearly explain what happened next, but it seems that some visitors were admitted to proximity with the baby and others were not, based on the intentions of the visitor. The Lakapijkuyu dancers represent those who were admitted. Those who were not admitted were somehow defined as outsiders and transformed into the animals that they were portraying, then they had to find refuge in the mountains. They are said to be represented by the viejos in a second Christmas dance, that of the Lakakgolo. Later the danza del Matarachín was split off from the Lakakgolo dance, essentially defining three classes of beings that emerged from those who attended Christ’s birth, each represented by their own dance. These three classes are not precisely defined in written sources available to me, so I must characterize them as best I can:

- Those portrayed in the Lakapíjkuyu dance represent the visitors who loved Christ immediately and became devout Christians.

- Those portrayed in the Lakakgolo dance appear to represent well intentioned beings who were still aligned with indigenous religious beliefs and practices. Although this is not obvious in the legend, apparently they attended the nativity scene to worship the birth of the sun. Since this was not a Christian response, God sent them away and they returned to the shelter of mountain and forest gods whom they had traditionally worshiped. In the process they were transformed into animals.

- Those later reassigned from the Lakakgolo group to the dance of the Matarachín represent those visitors who came with loyalties to indigenous gods that guaranteed their enmity to Christ. Their punishment was to become members of the community of the unhappy dead.

On reflection, the construction of the Lakapíjkuyu and Lakakgolo dances would seem to have been orchestrated by Roman Catholic missionaries to create a teaching instrument that demonstrated the winnowing of souls into those who truly accepted Christ versus those who did not; according to this teaching, the Indians had to choose to be among the elect or the damned.

But then there was the Indian layer of meaning. The Indians of the Sierra de Puebla solved this problem of salvation versus damnation by equating Christ and the sun, creating a new deity—Christ/sun. Therefore those dancing in both the Lakapíjkuyu dance and the Lakakgolo dance represented Christians celebrating the birth of Christ, but celebrating from both sides of the aisle, as it were.

But to accomplish this solution the elements of the Matarachín dance had to be split off, not by the missionaries but by the Indians. You might wonder why. This brings us back to a topic that I discussed at some length in my post about the Matarachín, the central importance of the concept of duality. It was not a simple thing to attach the sun to Christ, because the sun was not being attached to Christianity so much as Christ was being attached to the Indian system of gods. Christ was being inducted into a system based on duality. To maintain balance, it seems that Satan was also brought in on the other side, as an appendage to Tezcatlipoca. The beings in the Matarachín dance are associated with Tezcatlipoca and the devil.

Here is another mask from la danza de Lakapíjkuyu.

This mask was carved by Manuel Aldana Valencia (Don Lillo) of Coxquihui, Veracruz in 2010. I purchased this mask from the carver before it could be danced.

This mask has never even been provided with holes for a strap. It measures 7 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

Here is Don Lillo, the carver of this mask, in December 2010.

The Dance of Lakapíjkuyu reflects yet another myth about the newborn Jesus. Laka means “face” in Totonac and Pijkuyu refers to the Piskuyu or Garrapatera bird, so Lakapíjkuyu is translated as the face of the Garrapatera bird. It is said that when Christ was born he cried in distress because there was a cold wind with blowing dust. A flock of Garrapatera birds flew to the baby and shielded him with their wings, whereupon Jesus stopped crying. The black masks worn by the dancers have human features, but they are said to represent the faces of these birds. Several lines of dancers wear these apparently male masks while another line, dressed as females, have veiled faces instead of masks. As is so often the case when one learns something about a dance from this region, then one encounters a riddle such as this one—Why do the dancers wear human faced masks and not masks with the faces of birds? Although there is no published answer available, I can imagine two possible explanations: 1, The Garrapatera birds now have human faces because God rewarded their devotion by granting them human status, so that this is the origin story for humans on earth, or 2. The purpose of the dance is to inspire Christian humans to demonstrate the same level of love and devotion as those birds, and the dancers are modeling this ideal.

Thus far I have shown two masks by Coxquihui carvers for this dance, masks from the town where this dance is performed. Now I will show two more old and impressive masks in this Negrito style that were carved by Benito Juárez Figueroa, a carver who lived in various nearby towns in this region; apparently his masks were used interchangeably in either the Dance of Lakapíjkuyu or the Dance of the Negritos. They don’t differ substantially from the two we have just examined.

The first of these has a highly stylized design, with the mustache emerging from the sides of the nose and a rectangular goatee on the chin.

This spectacular old mask was obtained directly from the daughter of Benito Juárez, Alina Juárez Pérez, of Filomena Mata, Veracruz.

This mask is 6½ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3½ inches in depth.

This is a very old mask that is in a style used when Benito was a young carver.

The next mask is only different because the eyebrows, mustache, and goatee are artfully painted instead of carved in relief, and the mustache is in its more usual place.

This is another remarkable old mask by Benito.

This mask is 6 inches tall, 5½ inches wide, and 3½ inches in depth.

The back of this mask also appears to be quite old.

I hope that you have enjoyed learning about la Danza de Lakapíjkuyu. Next week I will discuss La Danza de Lakakgolo.