As I noted in last weeks post, to make sense of la Danza de Lakapíjkuyu and la Danza de Lakakgolo one must turn to a pair of legends, so I will briefly repeat them. Until the birth of Jesus, the world was dark, but at the moment of his birth an extremely bright star appeared (Christ and the sun were born at the same time). There were people and animals who apparently understood that the light was a gift from this newborn baby, so they gathered around him. The animals included the Oso (bear), the tlacuache (opossum) and the piskuyus (garrapatera birds). They danced for Jesus and he immediately stopped crying. Also the piskuyu birds spread their wings over the infant to protect him from the dust and wind. However a second version states that human visitors came dressed as animals, some to worship the infant, others to rob or kill him. Suddenly the sun rose, and in its light God judged the visitors. Some were permitted to remain and worship and they are represented by the Lakapijkuyu dancers. Others were transformed into the animals that they were portraying, then they went to find refuge in the wilderness (monte). They are said to be represented by the Oso (bear) dancer and the “viejos” in the Lakakgolo dance, who dance to commemorate the veneration of those visitors. At one time the Lakakgolo dance included representatives of all those visitors whom God had banished, but later the “Matarachín” and his Viejitos were given a dance of their own (discussed in my post of 09/08/2014).

The masks in the Lakapíjkuyu dance represent the faces pf the Piskuyu birds. The most remarkable masks in la Danza de Lakakgolo are those of bears. Here is an example that was carved in about 1990 by José González Hernández, of Comunidad Morelos, in the Municipio of Coxquihui, Veracruz. Vernon Kostohryz obtained this mask from José in 2005.

As you can see, this bear mask has an articulated jaw, meaning a jaw that is movable. Because it is attached with rubber bands, which can stretch, it tends to bounce when the dancer moves. The dancer must peer through the open jaws in order to see. This mask is 19 inches long, 11 inches wide, and 9 inches in depth.

The dancer can pull a string attached to the bottom of the lower jaw to open the jaws even wider.

The bear masks have a ring on the nose for a rope, so that the bear can be pulled around by another dancer.

The staining in the back of the mask from contact with the dancer’s hair is evident.

Here is a photo of José modeling a similar bear mask in December, 2008. This mask is currently in the collection of Vernon Kostohryz.

Sara Méndez Garcia (in Entre los Hombres y las Deidades: Las Danzas del Totonacapan, 2005, pages 140-141) wrote the only published account that I have been able to discover that is specifically about the Danza de Lakakgolo, also called the Dance of the Viejos. She began by a discussion of names. The Totonac name for the dance is lakakgolo (face of the old one or cara de viejo in Spanish). The dance has a second name in Totonac, lakakiwi (cara de palo in Spanish, or face of the pole or tree). She added that the dueño (master or patron) of this dance is Kiwíkgolo, in Spanish palo viejo (old pole). This personage is said to be the viejo del monte (the old one of the forest). In the Lakakgolo dance there are Viejo characters whose masks have human faces, but perhaps they represent Kiwíkgolo? I can only add that for the dances of this region, things are seldom what they appear to be, which is why I have subjected you to all of these linguistic clues.

In Huehuetla (in the Mexican state of Puebla), Bruce Lane was told that the puppets and masks in the Huehues dance were made of “living wood” (Notes on the Text of “The Tree of Knowledge”, nd). Now we may have been introduced to the master of the living wood, in the belief system of the Totonacs. Kiwíkgolo is apparently the supreme tree spirit, a tree with the face of an old man. As such he is the host of the monte (wilderness), which was said to be the refuge for those creatures who were expelled from the presence of the infant Jesus in the legend. As our insight grows, we may notice that these myths reveal two persistent parallel worlds, the world of natural spirits and the world of Christianity. Given these two worlds, apparently we need two dances to glorify Christ. The Christian worshippers are represented in the Lakapíjkuyu dance, while the worshippers from the natural world appear in the Lakakgolo dance. The false worshippers have their dance as well, the dance of the Matarchín.

Here are some further details about the Lakakgolo dance. The Oso (bear) is an obvious representative of the animals described in the manger story; in all of Mexico, this is the only dance known to me where dancers wear bear masks. Other characters include El Anciano and La Anciana (an elderly couple), soldiers, police, cowboys, and viejos. The literal meaning of viejos is old ones, but in light of the evidence in the last few paragraphs we can wonder whether the viejos might also represent living wood/dancing trees!

To better understad the Lakakgolo dance I turned to another researcher of the Sierra de Puebla, Guy Stresser-Péan (2009), who made a point in his book which may add to our insight— “indiginous myths establish that in olden times, animals were able to speak just like people and that they became mute when the sun appeared, assimilated to Jesus Christ” (p. 479). I perceive this as a reference to indigenous beliefs that the world had passed through four suns or eras, a belief that resembles the Christian teaching of two eras, one initiated by Adam and Eve and a second when the world was re-peopled by the descendents of Noah, after the flood. In the version found in the Sierra de Puebla, the current era began with the actions of the Spirit of Maize, leading to the birth of the present sun. With this new beginning, humans appeared on the earth (or perhaps reappeared, like Noah’s family after the flood), while animals remained frozen in their forest world, and the father of the Spirit of Maize chose to become a deer so that he could remain in that world. But because the people of this region have come to perceive Christ, the Spirit of Maize, and the sun as one entity—Christ/Sun, both the Christians and the animals can celebrate his birth, each from their own perspective.

Elsewhere, Stresser-Péan added yet another alternative story- “With the triumph of the sun, there existed from then on the reign of light and good. All humans died, and the Sun-God (Christ/Sun) was their judge, in accord with the faith they had in him and in his victory. The just were put in charge of peopling the world, and the others were turned into animals” (p.455).

The essence of all this is that the Lakapíjkuyu dance depicts the Christian celebration of the birth of Christ while the Lakakgolo dance celebrates for other worshippers the birth of the new sun, Christ/sun. By establishing this combination of dances the Totonacs could simultaneously demonstrate their Christianity and celebrate their earlier beliefs. However, to be consistent with their theory of duality, the Indians had to split the traditional believers into two groups, those that remained in the Lakagolo dance versus those depicted in the dance of the Matarachín.

Now I will show you three more of these bears. Oso #2 was carved by Leonardo Carcamo Palomino of Zozocolco de Guerrero, Veracruz. One ear was broken and although Leonardo carved an elaborate replacement, this was never painted.

This mask is 9¾ inches long, 12½ inches wide, and 6 inches in depth.

A wire loop through the nostrils provides the usual ring for the rope that pulls the Bear.

Staining from moderate use can be seen around the rim of the back, and on the strap (string).

The third bear mask was purchased along with a Viejo mask from the same dance; these came from the household of Don Mateo Espinosa Pérez, an old gentleman who lived outside of Zozocolco de Hidalgo, Veracruz. Both masks were carved in about 1990 by unknown carvers. This bear lacks a pulling ring.

This mask is 15 inches long, 8 inches wide, and 9 inches in depth.

The back shows moderate staining from use.

Here is the Viejo mask that danced with this Oso (bear).

This mask is 7¼ inches long, 5¾ inches wide, and 2½ inches in depth.

This Viejo mask demonstrates remarkable staining from use.

Here is Don Mateo Espinosa Pérez, in December of 2010. When we returned two years later to give him a copy of the book, we learned that he had died in the interim, so we gave the book to his family. Mateo was said to be over 100 years old.

Here is the fourth Oso mask. I found this undanced mask in Zapotitlan, Puebla in December 2012, when I was actually searching for the mask of La Mujer de las Cebollas (that mask appeared in my post of November 17, 2014).

This mask is 12 inches long, 7 inches wide, and 4 inches in depth.

Now I will show some additional masks worn by Viejos in la Danza de Lakakgolo. Like the first bear mask, both of these Viejo masks were carved by José González Hernández.

This Viejo mask was carved in about 1990. It is 7½ inches tall and 7 inches wide. It has a mysterious face, due to the rings around the eyes. This combination mirrors the paint on the first bear mask—a black face with lighter rings around the eyes—as if this dance character is associated with the Oso dancer.

This mask demonstrates the ear design typically used by José. Other masks by this carver, with similar ears, appeared in the post about the Matarachín dance.

The black faced viejo mask appears to have had little use.

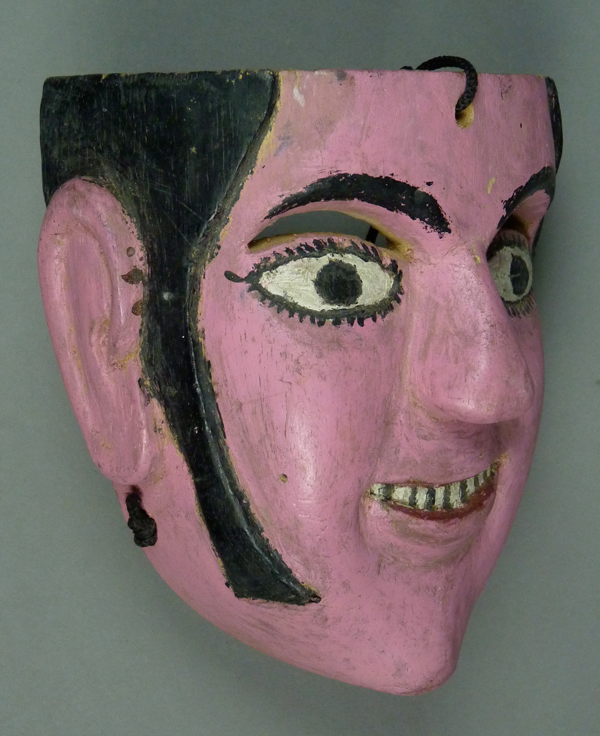

This pink faced mask was also carved by José González Hernández for the Lakakgolo dance. This mask is 7 inches tall, 6¼ inches wide, and 3½ inches in depth.

While the black mask has such a serious appearance, this pink Viejo has the exposed teeth that would mark a clown’s mask in other dances of this region.

This mask also demonstrates José’s typical ear design.

This mask has had only mild use.

I hope that you have found this dance interesting. Next week I will begin a series of three posts about la Danza de los Santiagueros.

Merry Christmas!