Please Note A New Feature Available in the Header—The Index to Mask Photos and Related Topics. For example, if one looks under “Tigres” there will be a listing of dates when Jaguar mask photos were presented.

My book about the masks and puppets of the Sierra de Puebla was officially published in September of 2012. During the five years that led up to this event I had made repeated visits to mountain towns in the Mexican states of Puebla and Veracruz in order to observe dances, meet and photograph carvers, and buy interesting masks. I promised to bring to each carver, dance leader, or representative family member that gave me assistance in my research a copy of my book when it was finally available. Therefore, my wife Lucy and I traveled to this area on December 6, 2012 for the purpose of giving away about seventy books; we flew back to Pennsylvania on December 16. It was during that trip that I became interested in the Mujer de las Cebollas character that I wrote about in my post of November 17, 2014. Now I am writing about that trip because it occurred at this time of the year, exactly two years ago.

The first visit on the tour was to the workshop of Silverio Ochoa Martínez, in San Juan Xiutetelco, Puebla, a town near the city of Teziutlan, Puebla. Silverio had confided to Carlos Moreno Vásquez that he had long doubted that he would ever see this book appear. He was delighted to have been mistaken. It is always interesting to see what Silverio has been carving, so I took this photo.

We see Silverio holding a feather headdress that he has just completed, along with a Pilato mask, as the headdress is to be worn by that character in the dance of the Santiagueros. There are additional feathers on the workbench as he was making a number of headdresses. On the wall you can see a variety of interesting masks by this carver. I was most puzzled by the oriental looking mask above Silverio’s head; he said that this was his invention. The mask on the right with green around the eyes and a knife in its teeth was described as a “pirate.” Obviously Silverio is a very talented carver. Most of the visible masks are traditional and are used in local dances.

One schedules a trip to the Sierra de Puebla with three things in mind—when does the wet season end, when does the weather turn colder, and when are the most elaborate fiestas? During the wet season the rains cause many unpaved roads to become impassable due to mud; sometimes flooding causes even greater hazards. There is no perfect solution, given the irregularity of nature, but the best compromise has been to go in December, just as the rains are sharply decreasing and before the swing to cold weather has gone too far, while the fiesta celebrating the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception occurs every year on December 8 and the Fiesta for the Virgin of Guadalupe follows on December 12. Both of these fiestas are important; the celebration for the Virgin of Guadalupe is particularly enthusiastic.

Our timing was good in those respects. There was little rain, the nighttime temperature was mild, and the fiestas were as elaborate as usual. However we encountered frequent dense fog in the late afternoon and evening hours, so dense that it was alarming to drive in, yet we usually had to find our way back to a place where there was a clean and comfortable hotel for the night. Carlos Molina Vásquez, our friend, guide, and driver, was definitely up to the task. Here is a photo that I took one morning to demonstrate the low lying clouds filling the valleys with morning fog.

One dark and foggy evening Carlos exclaimed that he had just driven over a huge snake that was crossing the road. He backed up several yards and we could all see a snake coiled by the side of the road, loudly hissing. We assumed that it was mortally wounded and when we returned the next morning the snake was clearly dead. Someone had thrown the snake’s body off the road and I took a photo.

As you can see, this was a large and beautiful snake, some sort of boa constrictor that we subsequently learned is native to this part of Mexico. It was about five feet long. The point of injury by the car’s tire is apparent. José González Galindo subsequently told us that the local name for such a serpent is a masaquata, a word that refers to a snake of the boa family.

Here is a photo of the three of us—Carlos Moreno Vásquez on the right, then my wife Lucy, and I am on the left. We are sitting in the large and comfortable stone house of Roberto Villegas Santiago, one of the finest local carvers. Note that we are all wearing hiking shoes to carry us over the rocky paths of this area.

Carlos is a campadre (a godfather) to the family of Marcelino Santos Castélan, who live in Hueytamalco, Puebla. They had permitted me to copy a family photo for my book, which showed Marcelino, his daughter, and several sons in costume for the Danza de los Moros y Cristianos. I thought that you would like to see this photo along with another from the book trip that shows some of them out of costume, because the comparison is entertaining.

In the photo above we see Marcelino dressed as a Moorish King, one son is an Angel, another represents death, and three other sons are Diablos, while his daughter portrays the Queen of the Christians.

In this more typical family photo, the daughter on the left has grown up quite a bit since her stint as the Christian Queen, her brother has likewise outgrown the suit of the smallest Diablo, and one can only be amazed to see the real Marcelino, shorn of his long false beard and wig. I believe that his wife was the photographer.

Nearby we visited Angel Bello Pérez, the proprieter of a hardware store in Hueytamalco and also the author of a book about the local performance of the Moors and Christians dance. Marcelino and his family members were featured in Angel’s book as well as mine. When I met Angel I finally knew a man whose hair was more curly than mine. Here he is in his store, with a stack of his books by his right hand. Note the vivid painted decoration on the poured concrete floor to mimic patterned linoleum tiles. In this rural town one felt dazzled to walk into a store that had such an array of modern tools and hardware.

We visited Eusebio Blas Román and his wife. Eusebio appeared in my book as a menacing skeleton who was brandishing an axe, another performer in the Moros y Cristianos dance in Hueytamalco. Here is a photo from the book of Eusebio in his costume.

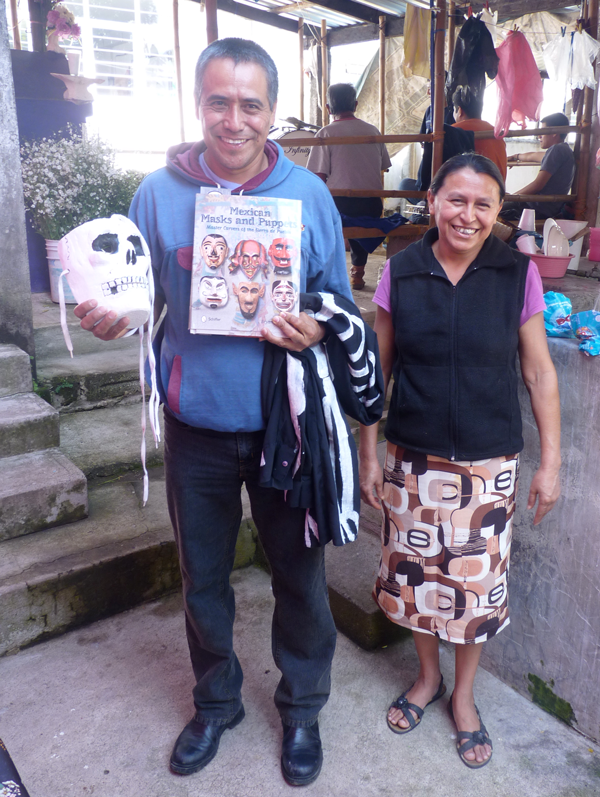

Here is a follow-up photo from the book trip of Eusebio with his wife. He presented me with the skull mask because he was so delighted by the book.

Nearby we found the carver of the Skull mask, Felipe Jiménez Martínez, who also appeared in the book wearing the mask of a Santaiguero that had been converted to one of the devil. Here is the photo from 2010 showing Felipe in costume. He is wearing another mask that he had also made for Eusebio.

Here is a photo of Felipe from December, 2012. He lives in Llagostera, Puebla.

In Colonia de Valle, Puebla, we had purchased Viejo masks for the Day of the Dead. This time we met the carver of those masks, Lucio Borniento Iturbide. He dressed in costume for a photo.

Lucio is a talented carver despite the loss of vision in one eye.

We visited Merella García, the adolescent girl who modeled her Negritos costume in Buenavista, Puebla for the book. She and the Negritos were dancing and we didn’t interrupt to take another photo. Here is one that I took in 2010. The wooden snake is an important element (prop) in the dance

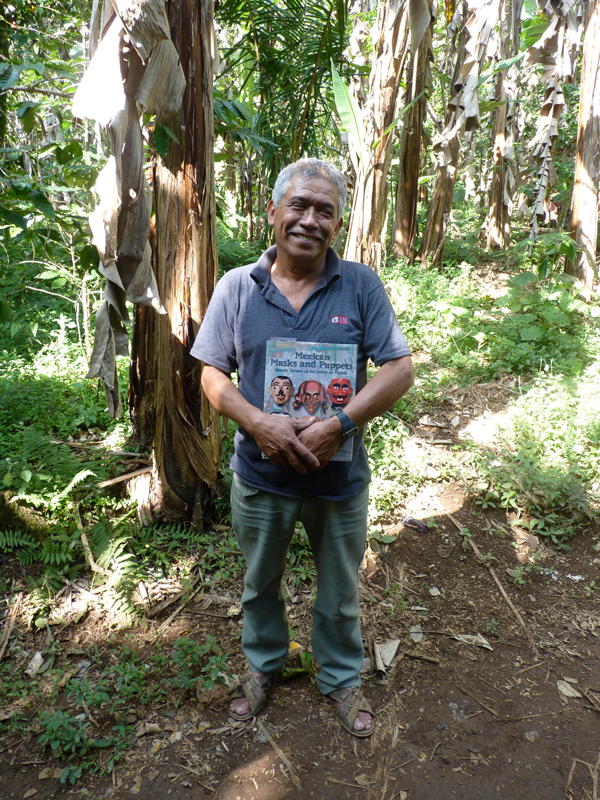

Next we visited Guadalupe Ortiz González, an elderly carver in Buenavista who makes such serpents for the Negritos dance from twisted vines and roots. He also makes handsome Chénchere (woodpecker) puppets; one was shown in my post of 7/28/14. He looks very formal in this photo, although it is more common for him to joke and grin, and he was obviously delighted to receive a copy of my book.

We visited a number of additional dancers and carvers.All were gracious and pleased to finally see the book. I will simply mention a few more to keep this from becoming too long.

In Coxquihui, Veracruz we got permission from Amalia Luna Galindo, the daughter of the Caporal of the Santiagueros, to photogragh a dance horse, masks, and other related objects which were then illustrated in the book. On this trip we had the honor of meeting her father, Miguel Juan Galindo. He proudly informed us that he had been the Caporal of the Santiagueros for 60 years, beginning at the age of 12! Here is Don Miguel, in front of the family altar. His dance horse, carved by José Gonzalez Galindo, is carefully cloaked, and one can see cups and vessels on the table in front of the horse to offer nourishment. There are three Santiaguero masks to Señor Galindo’s right that were also carved by José Gonzalez Galindo.

When we visited José González Galindo and his son, José González Diaz, we had a nice visit, but the big surprise was that the latter had carved a Mickey Mouse mask for his children to play with, they had tired of it, and it was for sale. I had never before encountered a mask in this region that was deliberately created as a children’s toy. I immediately bought it, of course, and here it is.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 10 inches wide at the ears, and 5 inches deep.

The back of this mask has obvious patina from skin contact. One see the dramatic differenc in color between the back of the mask and the broken edge. Regarding the latter, it seems that the children’s play was sometimes rough.

We had also returned to visit the Caporal of the Santiagueros in the town of Sabanas de Xalostoc, Veracruz, José Aparicio García. There were masks and a dance horse that we would have incuded in the book, but he was not home when we visited to get permission. In our book trip visit we found him friendly and welcoming, so I can now show some of these special things. Here is José Aparicio with his wife.

Here is a handsome dance horse belonging to José Aparicio that was carved by Juvinal Mendez of that community (Sabanas de Xalostoc). Note that it is also cloaked, as was that of Miguel Juan Galindo, and that it rests in its traditional spot on the family altar.

Don José removed the cloak to better reveal this beautiful horse.

José’s son dressed as a Santiaguero, wearing a mask that was carved by Alejandro Dominguez, and carrying a beautiful Sun Shield. In a later post about the Santiagueros dance I will show some other Sun Shields, as every one is unique.

Here is a close-up photo of the Sun Shield, symbolic of the allegience of the Santiagueros towards the sun.

Near Entabladero, in the small community of Sabaneta, Veracruz we visited Don Salvador Mejorada Romero, the former Caporal of the Tejoneros there. Now his brother-in-law is the Caporal. As in my last visit, Salvador was an extremely gracious and active host, who launched into a lengthy explanation about aspects of the Tejoneros dance. I will mention a few highlights, particularly since this was information that was not available to include in my book. Those who dance as Tejoneros do so because they have taken a vow to dance in honor of the Virgin of Guadalupe. That explains the observation that the Tejoneros in this community have the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on their conical hats. In this context of Christian service, the dancers are expected to observe strict limits, such as the avoidance of sexual contact with one’s wife for a specified period of days before dancing. If a dancer fails to honor this restriction, he is encouraged to confess this lapse, so that he can be ritually punished. It is not the case that the other dancers want to punish the transgressor, but rather that they wish to cleanse him through ritual punishment so that his soul is not in danger. Don Salvador also demonstrated how the Caporal holds an incense burner with burning copal, blessing the four directions and smoking the dancers.

In Entabladero we happily visited Omar Jesús Fajardo González, the Caporal of his Tojoneros group and a man who had demonstrated for us many aspects of the dance. In a photo from my book, Omar demonstrates how a puppeteer wraps his fingers with elastic bandages to provide a surface that grips the hand puppets.

In response to my gift of the book, Omar offered to give me a number of interesting things such as the traditional suit for a Payaso that he has always worn. Lucy and I resisted his excessive generosity but I did accept with gratitude a Tejonero mask that was said to be 40 years old. Here it is. I especially want to point out that the happiness of such dance leaders as Omar about the book did not seem to reflect the inclusion of their photos, but rather they were thrilled that someone would take such pains to honor their culture and their related religious beliefs.

This mask has brand new paint, giving the impression that it has never been danced. It is 7 inches tall, 6¼ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

It has a distinctive ear design, one that is unfamiliar to me.

The back shows great wear, supporting the history that it is 40 years old, after all.

One of the moments that gave me the greatest pleasure during this trip was when I met the new Caporal of the Negritos in Olintla, Puebla, José Francisco Vega. When I last visited, it seemed that I was witnessing the end of mask use by the Negritos there. The man who was the Caporal then actually sold me one of the last masks that was in use, apparently because there were too few masks to maintain the tradition and no one wanted to be the one to still wear a mask if the others did not. But since then that Caporal had died, and the new one decided to carve an entire new set of masks, one for each Negrito dancer. Now they all wore masks. He allowed me to buy one of the new Negrito masks.

This is José Francisco Vega, the current Caporal of the Negritos in Olintla, Puebla.

This is the Negrito mask that I purchased from José in order to document this new era for the Olintla Negritos. It is 7 inches tall, 6¼ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

Our final visit to a mask carver was with Don Teodoro, a wonderful old gentleman of uncertain age who was said to be at least 100 years old. On that chilly and foggy night he was sitting on a low stool in front of an open fire that burned on the floor; the smoke escaped through an opening in the door. We sat there with him and gratefully accepted a cup of cocoa from his daughter or daughter in law. He was in good spirits. He died several months later.

During this entire trip it fell to Carlos to make an elaborate formal presentation of each book. At the end I was the one to imitate his now familiar style as I gave a copy to him. Lucy and I so appreciated his energy, resourcefulness, and grace. We couldn’t imagine having accomplished this arduous task with anyone else.

I hope that you enjoyed this account. For the next two weeks I will discuss the dances in the Sierra de Puebla that are especially related to Christmas.

Bryan, this is by far my favorite post. What a joyous trip – and giving back is what it’s all about. Congrats. Tom

Hey Bryan, This is a good follow up post to your book. You are very generous. Tom

Thank you Tom.

Bryan

Tom

This trip involved a great deal of effort, to plan and to accomplish, but it came together in such a gratifying way, to see all of these lovely people again!

I am grateful for the experience.

Bryan

This is a wonderful website. The last entry is wonderful and unique

John

Thank you.

Bryan

Pingback: Moro Masks From the State of Mexico VI | Mexican Dance Masks