This week I will shift to another subject—The Day of the Dead—inspired by a recent purchase on EBay. The seller, an online auction service, offered a set of five masks. These were obviously old and worn in appearance. Furthermore, they demonstrated numerous pinholes on their surfaces, as if they had been infested with wood boring insects, or they had been carved from wood that had been previously infested. Such masks can be very fragile, but these seemed to have normal strength, without obvious broken areas, except for a split out section on one of the ears of the Chivo, and a small broken area on the chin of the Calavera.

By now you may be wondering why anyone would buy such damaged goods. In fact, I had at least two reasons. To begin with, the carving of these masks was of very high quality, and there were several interesting designs. Masks of monkeys are very uncommon in the Mixtec towns, so their presence was of major importance, the skull mask was a masterpiece, the Viejo mask was superb, and the goat mask was also well carved. Therefore I was willing to gamble that they were not as fragile as they looked. Furthermore, each of the five masks had a small paper tag, in barely legible Spanish, that explained its role in “La Danza de los Muertos” (The Dance of the Dead). These tags were yellow with age. The information on the tags had evidently been copied from older labels that were pasted on the backs of each mask, but all that remained of the original labels were small corner fragments. No writing had survived on those scraps. It seemed possible to reconstruct the dance by translating and then combining the five descriptions from the tags, which seemed a remarkable opportunity to rescue an obviously old tradition from oblivion (salvage anthropology). The consigner had also provided the seller with limited further information. The masks had been collected in a small town in the Mixteca Alta of Oaxaca—Santa María Peñoles—in the 1930s or 1940s, and the last owner had purchased them from the original collector, in Mexico, in the late 70s. There had been additional masks in the group, with human faces.

For many centuries, the Mixtec Indians inhabited their own region in the present Mexican state of Oaxaca. The Mixteca, the territory of the Mixtecs, extends from the Costa Chica (little coast) of Oaxaca to the highland plateau of that state. It is customary to speak of the Mixteca as a region divided into two parts—the alta (highland) and the baja (lowland), which lies along the Pacific coast. Santa María Peñoles is a highland town that lies to the west of the city of Oaxaca.

Note that the correct pronunciation of Oaxaca is contrary to what many expect. One says “Wah-há-ka,” where each “a” has the same sound as that letter in “watch.” Think of Baja, California, as another model.

Here is an overview of the “Day of the Dead” celebration in Mexico. This appears to be a complicated story that has many unknown details, but there are some obvious starting points.

1. Prior to contact with Europeans, the Indians of Mexico already believed in an afterlife, and perceived death as a passage from one phase of life to another. They had burial rites, and they viewed the souls of the dead as potentially dangerous to the living, necessitating special funeral practices and precautions.

2. The Roman Catholic Europeans had their own beliefs and concerns about the dead. In particular, they celebrated the memory of the Christian Saints each year on November first, “All Saints,” and they remembered all of the remaining dead on November second, “All Souls Day.”

3. When the Spanish brought Christian missionaries to Mexico to convert the Indians, these two traditions were immediately blended, such that the European tradition was adopted, but yet indigenous elements crept in to alter its practice. This is an example of something that anthropologists call “syncretism,” in which a conqueror imposes a new religion, but elements of the native religion are somehow retained, usually covertly or in a disguised form.

4. In Mexico the terms “All Souls” and “All Saints” have merged into one, so that many Mexicans believe that the souls of most of the dead return each year to visit their living relatives for 24 hours on November first. This is an occasion of great joy for the living as they savor the belief that they are momentarily reunited with lost relatives. But then there are many local versions regarding the specific days when certain of the dead can be expected to visit. For example, those who were murdered or who died violent deaths may be expected on some other day or they may be perceived as unable to visit at this time of year. The souls of young children are often greeted during the 24 hours after November first.

5. In fact, All Souls is one of two times in the year when the souls of the dead may visit; the other occasion is at the time of Carnaval, the holiday that North Americans call “Mardi Gras” or “Shrove Tuesday.” There are regions in Mexico where there is apparently concern about possible visitations by the malevolent (or “unquiet”) dead, prompting the development of dances and related activities that are meant to mimic and thereby counteract such risks, and these can occur in November or during Carnaval. There were similar European traditions that have been reduced to our familiar Halloween activities.

With this background in place, we are ready to investigate the evidence for a very specific dance tradition from Santa María Peñoles, in the state of Oaxaca. I will present photographs of the five masks, including with each mask views of both sides of its paper label and my transcription of this. Then I will share my translation of the five labels. This will permit us to reconstruct this local version of the Dance of the Dead.

Here are the five masks ordered according to their numbered tags.

Mask #1—a large mask with a monkey’s face, the “Nahual Major.” Nahual (or Nagual, in Spanish g and h are often silent letters), which can mean sorcerer, is absent from many dictionaries, but Donald Cordy discussed this word and concept at length in Mexican Masks (e.g. page 174). He stated that nagual means “guardian spirit” and usually refers to an animal spirit that is part of a person’s soul. He also said that many Mexicans still believe in the concept that each person can have his or her own nagual, although now the word tonal is frequently substituted for nagual. Cordry believed that the Indians of Mexico had masks of naguales (plural form) and that the Spanish relabeled these as the masks of diablos. Major (pronounced “má-yor”) is an adjective that means lead, head, or chief.

The Chango Major mask seen from the front. The vision slits almost seem like an afterthought. It measures 9″ x 6½” x 4″.

A side view of the Chango Major mask. Note the large holes above the ears for the attachment of a strap.

The back of the Chango Mayor mask. On all five masks we will see vestiges of an old label, measuring about 2½” square, that had been applied to each back.

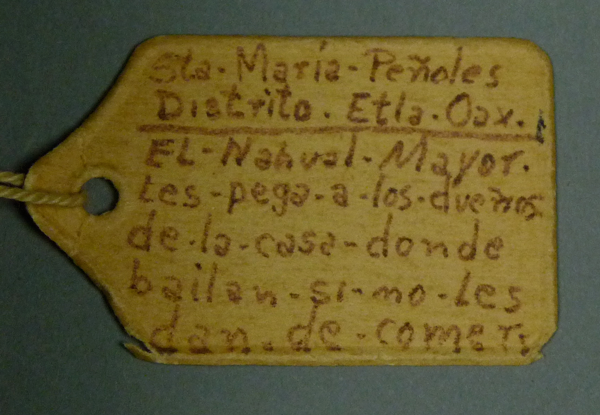

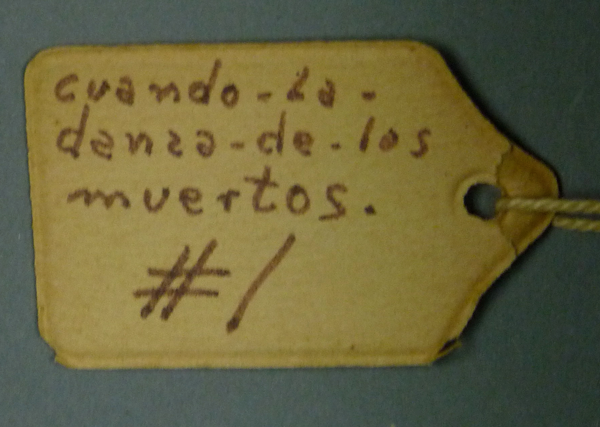

The front and back of the paper tag for mask #1.

Here is a transcription of tag #1—“Sta. María Peñoles, Distrito Etla. Oaxaca. El Nahual Mayor. Les pega a los dueños de la casa donde bailan si no les dan de comer, cuando la danza de los muertos. #1”

Mask #2—a smaller “Chango” mask.

The Chango mask seen from the front. Note that although this mask is a smaller version of the Nahual Major, it lacks vision slits. Chango is variously translated as monkey, gorilla, etc., but this word is absent from most formal published dictionaries, where one finds instead “mono” for monkey or ape, and “gorila” for gorilla. As the junior edition of the Nahual Major, the Chango is apparently another nahual. This mask measures 7″ x 5¾” x 3½”.

A side view of the Chango mask. Note the large holes above the ears for the attachment of a strap.

The back of the Chango mask

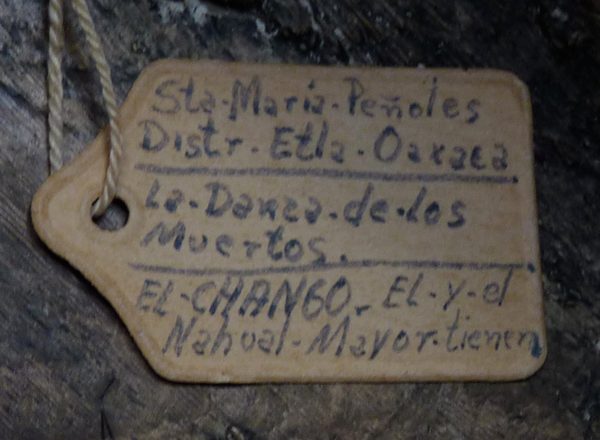

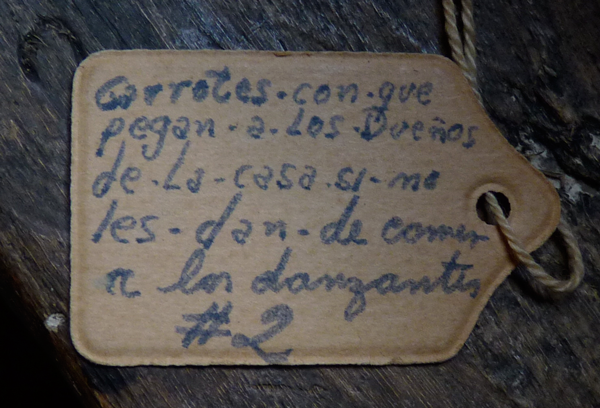

The front and back of the paper tag for mask #2.

Here is a transcription of tag #2 —“ Sta.María Peñoles, Distr. Etla, Oaxaca. La Danza de los Muertos. El chango—El y el Nahual Mayor tienen garrotes con que pegan a los dueños de la casa si no les dan de comer a los danzantes. #2.”

Mask #3—a human faced mask, the “Viejo Major.” Viejo or “old one” sometimes refers to someone who is dead, so this is the leader of the dead.

The Viejo Major mask, seen from the front. Note the third opening above the left eye; does this represent a wound? This mask measures 8½” x 7″ x 4½”.

A side view of the Viejo Major mask. Note again the large holes above the ears for the attachment of a strap.

The back of the Viejo Mayor mask. Note again the third opening above the left eye.

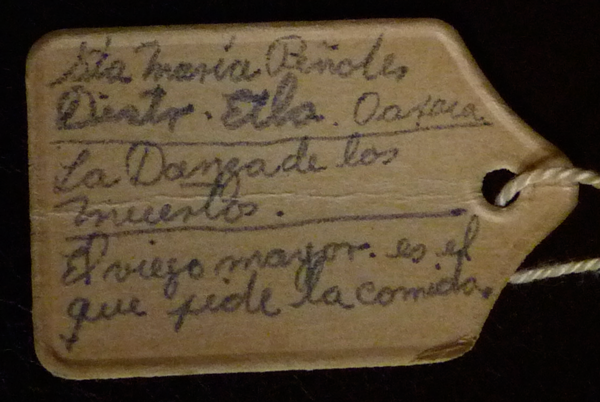

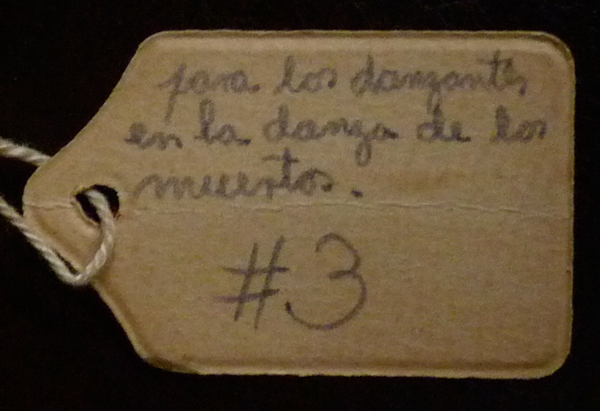

The front and back of the paper tag for mask #3.

Here is a transcription of tag #3 —“Sta María Peñoles, Distr. Etla. Oaxaca. La Danza de los Muertos. El viejo mayor. es el que pide la comida para los danzantes en la danza de los muertos. #3.”

Mask #4—a small mask of a goat, “el Chivo.”

The Chivo mask seen from the front. It measures 8¼” x 5½” x 3½”. Like the Chango and the Calavera (to follow), this mask lacks vision slits.

A side view of the Chivo mask. Note again the same large holes, this time behind the ears, for the attachment of a strap.

The back of the Chivo mask

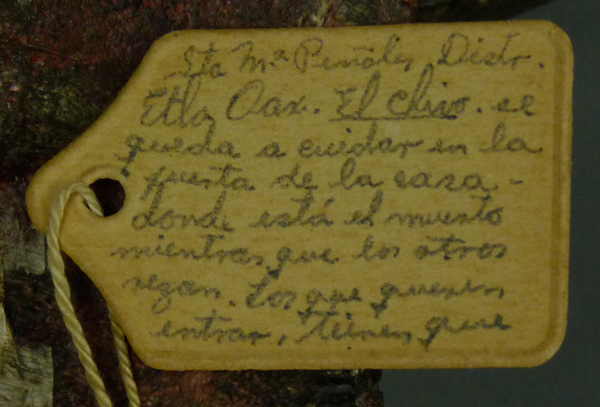

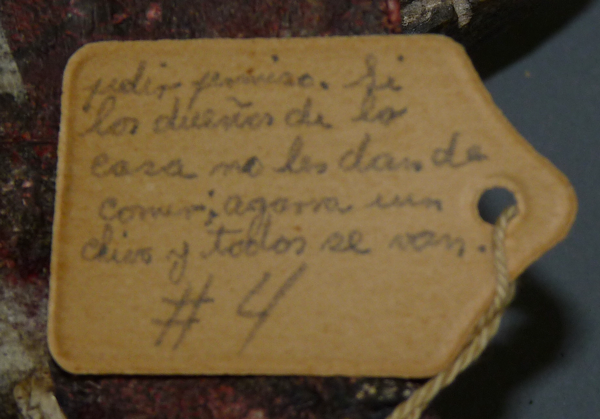

The front and back of the paper tag for mask #4

Here is a transcription of tag #4 —“Sta. Ma Peñoles, Distr. Etla, Oax. El chivo se queda a cuidar en la puerta de la casa- donde está el muerto mientras que los otros rezan. Los que quieren entrar tienen que pedir permiso. Si los dueños de la casa no les dan de comer, agarra un chivo y todos se van. #4.”

Mask #5—a mask with the face of a skull, la Calavera. It has a wonderful abstract design.

The Calavera mask seen from the front. It measures 8½” x 6¼” x 3″. This mask lacks vision slits.

A side view of the Calavera mask. Like the other four masks in this set, the Calavera mask has prominent holes for the attachment of a strap.

The back of the Calavera mask. At chin level, part of the rim has broken off, exposing the natural color of the wood.

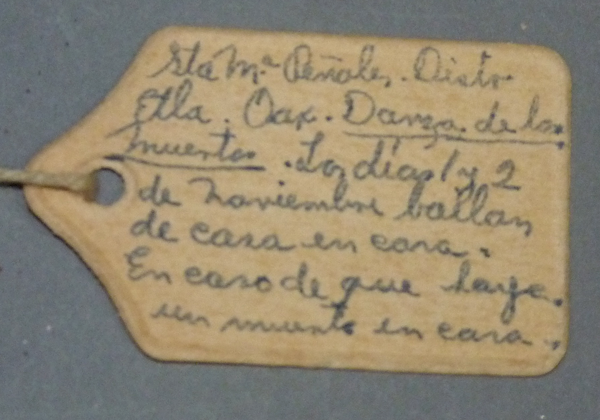

The front and back of the paper tag for mask #5, from the Danza de los muertos.

Here is a transcription of tag #5—”Sta Ma Peñoles, Distr Etla. Oax. Danza de los muertos. los días 1 y 2 de Noviembre bailan de casa en casa. En caso de que haya un muerte en casa la Calavera se pone delante del cadaver y los otros rezan. #5”

The other human faced masks that have been separated from this set are assumed to be additional Viejos. I will be curious to learn whether they have vision slits.

Now that you have had the opportunity to see all five of the masks in this set, along with their respective tags, we are in a position to link what we have learned to create a composite picture of the Dance of the Dead.

#1 “The chief Nahual. During the Dance of the Dead the dancers pretend to menace the master and mistress of a household [where they are dancing], if they are not offered food. ”

#2 “The Chango and the Nahual Mayor have sticks or staffs with which they threaten the owners of the house, if they don’t offer to feed the dancers.”

#3 “The chief of the dead [el Viejo Major] is the one who requests food for the dancers.”

#4 “The Chivo positions himself to guard the entrance to the household where a death has occurred while the other dancers pray. Those who wish to enter must seek permission [from the Chivo]. If the hosts do not provide food, the dancers collect the Chivo and they all depart.”

#5 “On the 1st and 2nd days of November they dance from house to house. In a house where there is a dead body the skull mask is placed in front of the corpse and the others pray.”

Now I will assemble these facts to create a picture of the dance. There is a group of dancers who perform on November 1 and 2, in the context of the All Souls celebration, by dancing from house to house. They pretend that they are the embodied souls of the dead. There are ghouls (dead humans) and skeletons, accompanied by animal spirits (nahuals), represented by a lead ape or monkey and his assistant, plus a goat. Evidently all five dancers wear masks, although only the Nagual Major and the Viejo Major wear masks with vision slits. I suppose that the others either carry their masks as symbols of their respective roles or they wear their masks on their foreheads like the brims of baseball caps, leaving the wearers free to see underneath the edge of the mask. It does seem that the Skull dancer deliberately places his mask in a protective position when the group enters a house where there is a dead body. It is less clear whether the goat guards with his mask on versus the possibility that he might place the mask next to the doorway to guard the entrance. I am guessing the former, that all five masks were worn by dancers, because each mask has the same drilled holes for the attachment of a strap.

The dance group visits two types of houses. One type consists of homeowners who have lost relatives to death in years past and who are presumably being visited by the deceased. In this case, the dancers evidently serve as visible surrogates for the visiting souls, providing an additional opportunity for the household to demonstrate its desire to welcome such visitors. A second group of households is actively mourning the recent death of a relative and the body is still in the house, presumably accompanied by its soul. In the latter situation the dance group is expected to pray for the soul of the deceased, perhaps in order to encourage its departure.

There are similar traditions in other regions of Mexico. Most generally it is customary in many communities for a family to put out food for the visiting dead and they make it a point to provide the favorite foods of the deceased. An extension of this practice is the feeding of living humans who imitate and personify the visiting souls (in effect, feeding by proxy). For example, there is the Xantolo tradition among the Otomí Indians in the state of Hidalgo. In Másacaras, Estela Ogazon wrote on behalf of herself and her husband, Jaled Muyaes, about this dance. The Xantolo dancers are supplicants who visit the houses of their town on All Souls Day seeking food and drink. I saw the Xantolos dance in twin lines in Huejutla, Hidalgo, as if the dancers were modeling their steps on the Matachines dance. In my book (Mexican Masks and Puppets) I described the Dance of the Matarachín (which is entirely separate from the Dance of the Matachines), in which there are many different characters from all walks of life, but usually regarded as evil, and led by the devil; they dance eight to eleven days after All Souls Day. In fact, their dance seems to be positioned partway between that holiday and subsequent performances related to Christmas, as if in apposition to both. That is, the “evil souls” that dance with the Matarachín are being contrasted with the positive or harmless souls that are welcomed on November 1, and the Matarachín character represents a deformed baby who stands in contrast to a perfect baby to follow—Christ.

In summery, the dance at Santa María Peñoles, Oaxaca, appears to be a local version of dances that are found in various parts of Mexico. The use of Chango characters to represent animal spirits is of particular interest because one seldom sees masks of monkeys in other Mixtec areas, but Monkey characters are commonly seen in the performances of Mayan speakers in the neighboring state of Chiapas and in Guatemala. Skull masks, on the other hand, appear in many other regions and dances. Although skull masks are commonly attributed to performances related to the Day of the Dead, they actually appear in other unrelated dances such as Carnaval, Seite Vicios, and Tres Potencias.

Next week I will tell some more about the Danza del Matarachín.