In March of 2001 I made one of many visits to Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazon in Mexico City. I discovered that they had some masks for sale that had obsolete Mexican coins glued to their faces. Jaled told me that the money on the masks represented the thirty pieces of silver that were paid to Judas Iscariot for his betrayal of Christ. On that occasion I purchased three of these masks—a human faced mask with a droll smile, a jaguar, and a third with a primitive human face. I had initially thought that these were used in the Tlacololeros dance.

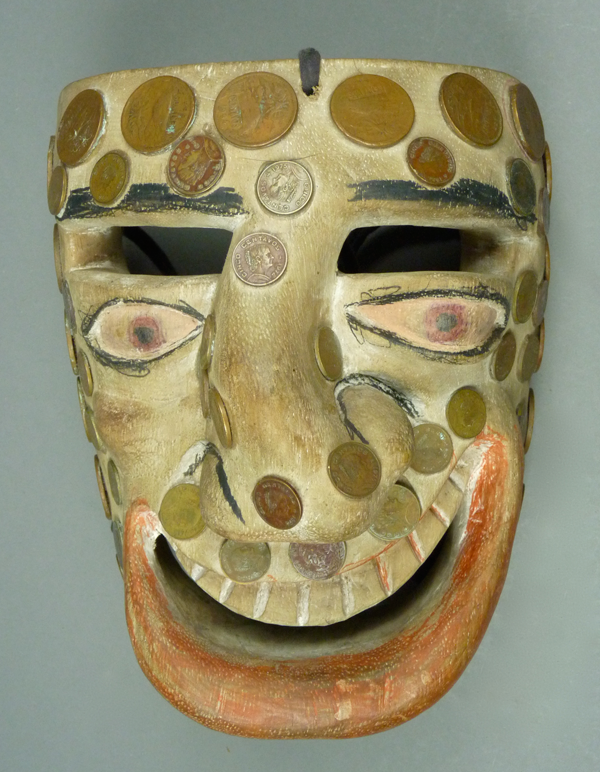

Here is the large human faced mask with the droll smile. I was particularly drawn to this mask.

This mask is 9½ inches in height, 7½ inches wide, and 6 inches deep.

On the back there is evidence of mild wear.

Jaled told me an amusing story related to the discovery of these masks. He was offered a mask that had spots of glue on the face. On inquiry, he learned that the glue had held coins, but the seller removed them in an effort to make the mask more salable. Pursuing this further, Jaled managed to buy a number of these masks with the coins in place.

Here is the Tigre (jaguar) mask.

This mask is 10 inches in height, 6½ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

Money provides the jaguar’s spots.

Differential staining on the back indicates that this mask has had moderate use.

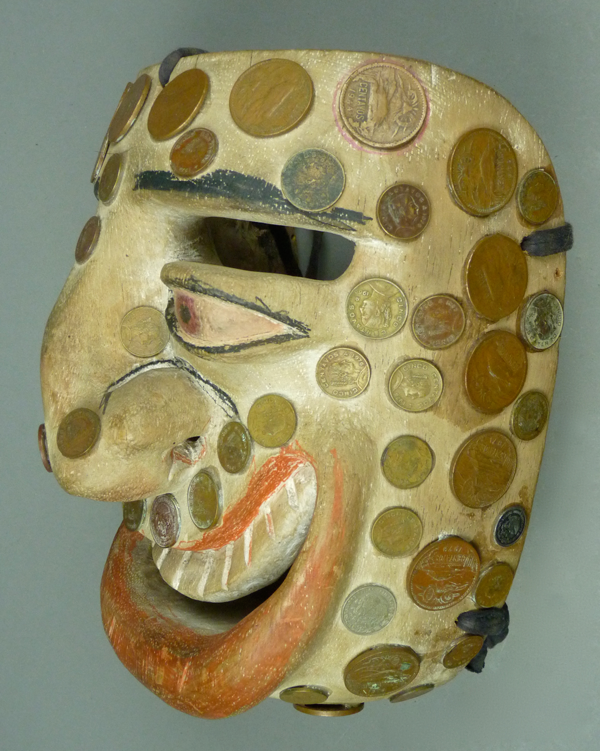

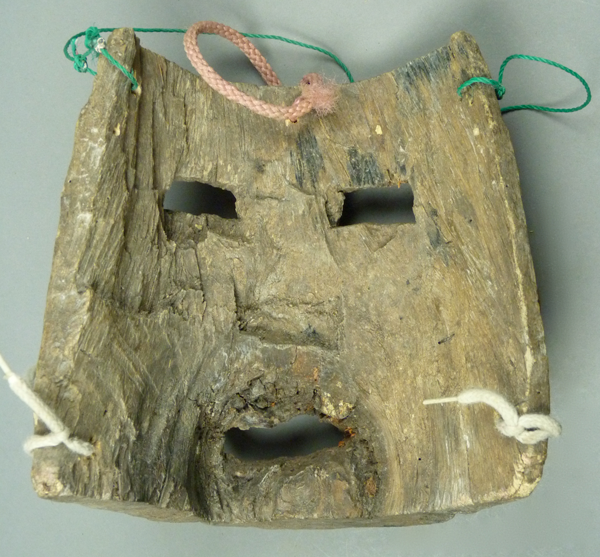

The third mask has a primitive and unusual form. It appears to be much older than the other masks in this group. Although I suppose that this mask was intended to depict a human face, I can’t rule out the possibility that it might represent some animal. This could be another jaguar mask, or perhaps a dog, although the absence of teeth or fangs argues against these possibilities.

This mask is 7 inches in height, 7 inches wide, and 4½ inches deep.

Because the back of this mask lacks edges at the top and bottom to stabilize the mask on the face, many straps (or cords) were necessary to bind it firmly in place. The staining from long use is apparent.

Generally speaking, one commonly sees masks with such an “open” back that have been carved for tourists. It is unusual to find such a form on a danced mask.

In a later visit of November 2002 I found that there were other masks from this dance that had elaborate wood and tin helmets; these helmets had been constructed from found objects such as an old metal lampshade. I added two of these masks with headdresses to my collection. Jaled explained that these were all representations of Judas. He showed some other objects from the dance that he had kept for his collection. I particularly remember a coin slot with a serpentine shape that was carried by one of the dancers, apparently to receive donations. Now, with the benefit of my review of other Judas and related dancers in recent posts, we can easily place these characters and their dance within the Semana Santa (holy week) tradition.

This mask is 12 inches in height without the helmet and 25 inches with the helmet, 7 inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

This mask demonstrates the remarkable carving that drew me to this group of masks.

The staining from use on the back of this mask is only mild. The chin strap held mask and helmet in place.

As far as I know, Jaled Muyaes invented this simple stand to permit him to hang such mask/headdress combinations on the walls of his house. Later his interest in metalworking progressed to the point that he shifted his attention to the creation of metal sculptures, including masks. I will write about this chapter of Jaled’s life in a later post.

This is the second of the masks with helmets. A recycled metal lampshade serves as a visor, not unlike the visors worn by Roman soldier characters that we saw in earlier posts.

This mask is 10 inches in height without the helmet and 18 inches with the helmet, 7 inches wide, and 4 inches deep. The corners of the visor (lampshade) are 10 inches apart.

Again on this mask there is a pattern of differential staining that is consistent with mild to moderate use.

I asked Jaled Muyaes where these masks were danced. He told me that the name of the town was San Judas. There is a place in Guerrero named San Judas Tadeo, but I have found no evidence that these masks were ever used there. If you know more on this subject, please tell me.

Next week I will begin a series of posts about Judío or Fariseo dancers in the Mexican state of San Luis Potosí.

I have never seen coins on these kinds of masks. Truly amazing. What is interesting on the ones with helmets is that the masks look older than the previous three but the coins on them are much newer. The third one, to me, is way off the charts. Thank you Brian.