Two weeks ago I had introduced the subject of Judas and related dancers who perform during Semana Santa (Holy Week) throughout Mexico. That post focused on the Judas dancers in Michoacán. Last week I discussed additional dancers of this type who dance as Fariseos; those masks were from Guanajuato, Jalisco, and Queretero. Next week I will introduce you to Judas masks from Guerrero that carry coins on their faces to mark their identity and in subsequent weeks I will tell you about the remarkable Judio masks used in the Mexican state of San Luis Potosí.

This week we will consider masks worn by Roman soldier figures during the Holy Week drama—Centurian masks from Chiapas and the State of Mexico and a Robeno (Roman) mask from the state of Hidalgo—along with hand made tin helmets worn by unmasked legionnaires in the State of Mexico and a very rare mask worn by the performer who portrays Christ. Usually the Christ impersonator does not wear a mask, but simply period clothing and a crown of thorns, but this mask from the State of Mexico even includes those thorns.

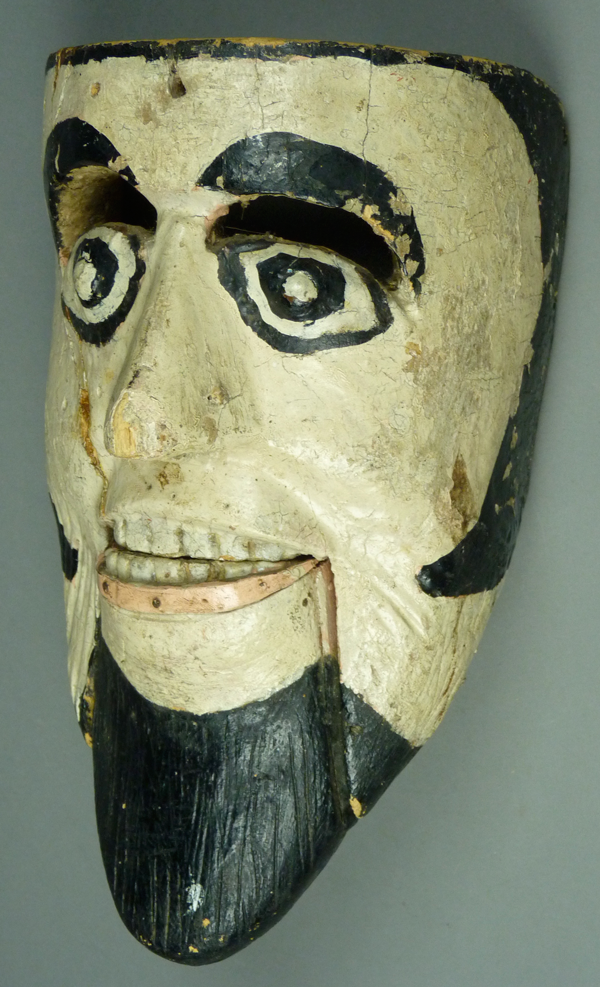

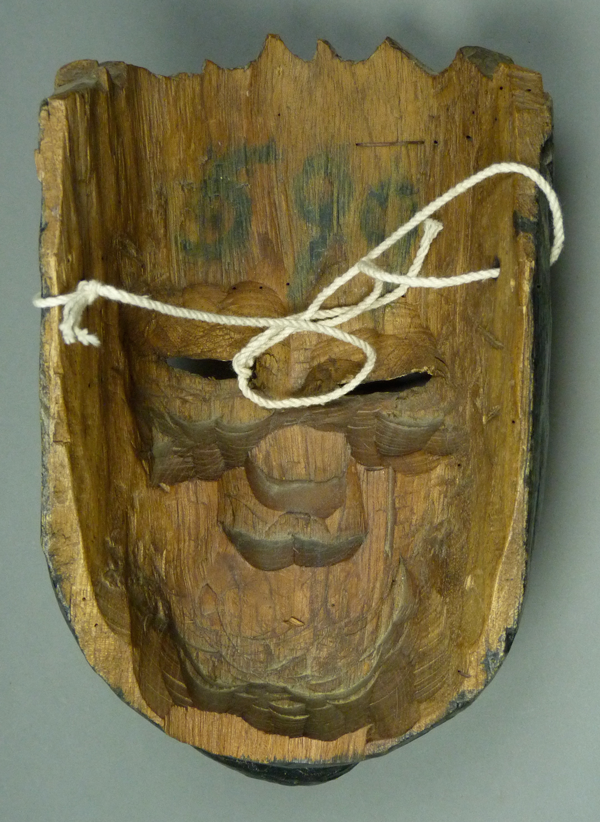

I will begin with the Robeno mask from Hidalgo.

Robeno masks have had very limited exposure in books about Mexican masks. Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazon planned to publish a major work about Mexican masks that would have included Robeno masks, and they included two in a promotional datebook—Agenda 1998—before Jaled’s energies shifted to such artistic endeavors as drawing, collage, and sculpture. There was another Robeno mask in the Mascaras catalogue from the UNAM show ((Ogazon 1981, plate 38 and pages 93-94); this and one of those in the datebook resemble my Robeno, although those two seem older and by a different hand. All of these published examples were from the same place, San Augustín Metzquititlán, Hidalgo.

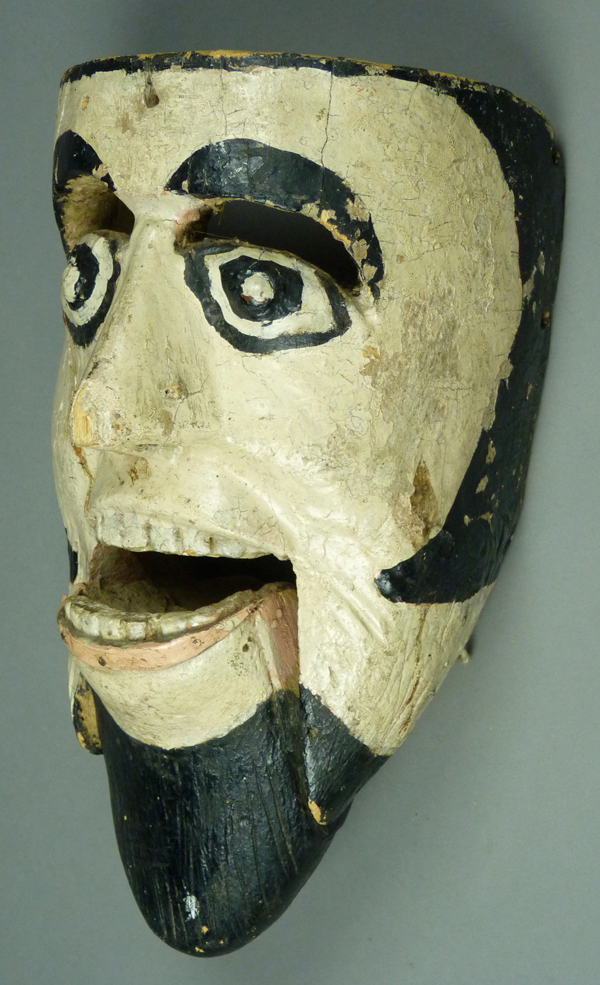

I got this Robeno mask from Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazon in 2000. It had been infested with boring insects and Jaled had dipped it in kerosene to kill the bugs. To this day it carries the scent of kerosene. Small holes from the infestation are visible above the painted eyebrows and on the back, but fortunately the mask did not suffer disfiguring damage. It is a handsome mask with its faceted cheeks that contrast with its baroque hair and beard. Note the staple at the top of the mask that substituted for a hole in the forehead for the top strap. One gets the impression from this photo that there is also such a hole, but the back view reveals that this is an illusion.

Note the baroque nature of the hair, mustache, and beard, which stands in sharp contrast to the modernistic faceted carving of the cheeks and brows.

This mask is 8 inches tall, 7 inches wide, and 6 inches in depth.

On the one hand, this view of the back reveals a number of small pinholes that are typical for an infestation with boring insects. In the US these insects are sometimes called powder post beetles, but I suspect that they go by many different names, the world over. The back also demonstrates the uniform glazed appearance that results from treatment for such an infestation with kerosene. It is also possible to see that there had been differential staining from use, prior to this treatment; for example, oils from the skin of the dancer’s nose darkened a spot on the center of the back of the mask and the rim is obviously darker than the areas under the eyes.

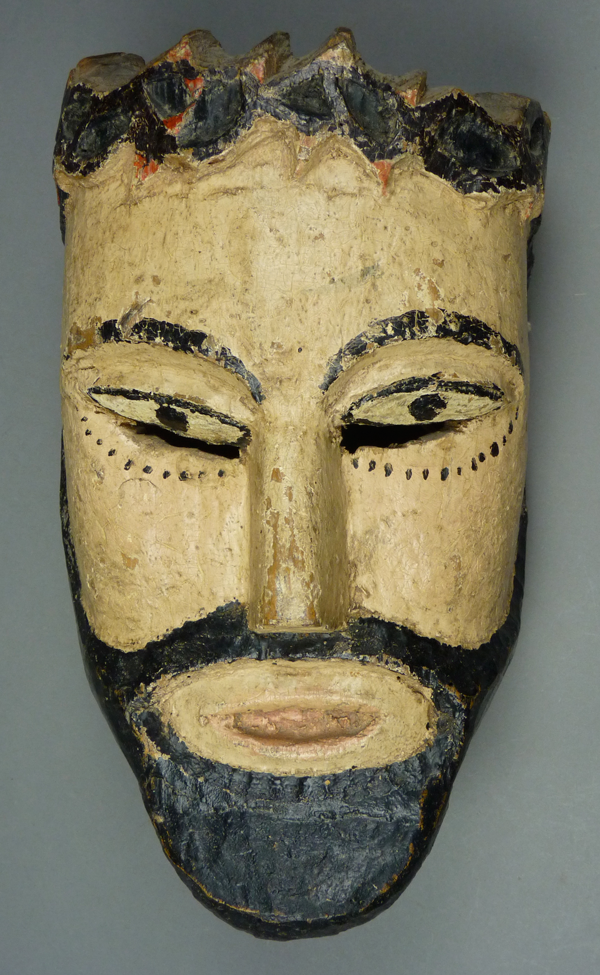

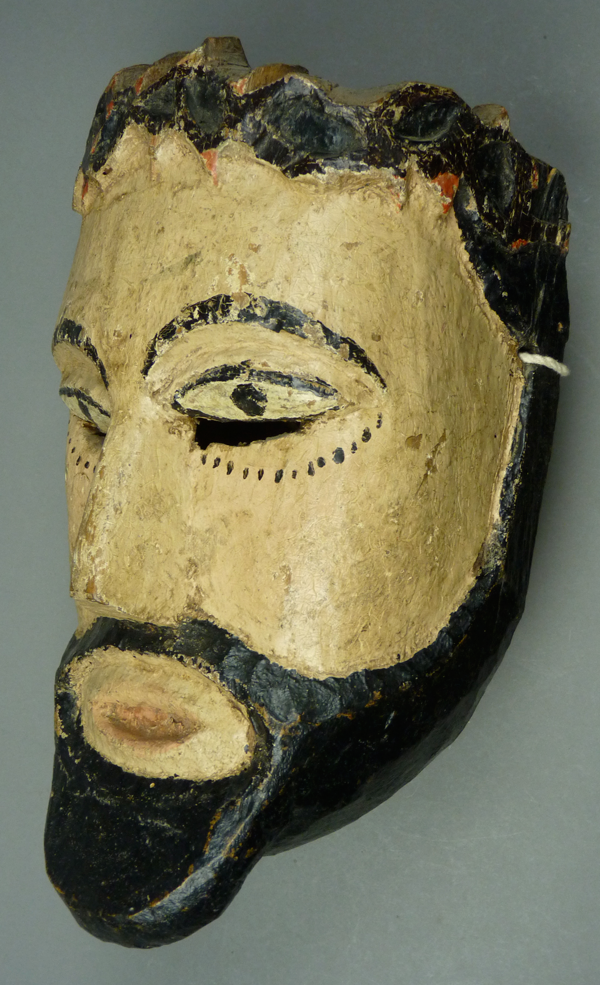

Next is a Centurion from Chapopotenango, Chiapas. I got it from Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazon in 1997. Its stylized face has a stern or even cruel expression. There is a knob on the forehead that has been carved in relief.

This mask is 8½ inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 3½ inches in depth.

The small relief carved ears are difficult to see.

The back of this mask is dark from long use.

The rest of the masks and other objects in today’s post are all from the State of Mexico. Here is a Centurion from Atlacomulco in the State of Mexico. At some point it split in two and had to be glued back together by its owner. It has an articulated jaw. I purchased this very old mask from Spencer Throckmorton in New York City, in 1995.

This mask is 10 inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 4½ inches in depth.

Say “ahhh.”

These jaws close with a clack.

Although it is possible to convert a mask to the articulated style by simply sawing along the desired outline of the jaw, this mask has a jaw that could not have been easily created in that manner (due to the beveled edge) and it is only crudely fitted to the rest of the mask.

The next mask is unusual because someone has carved the name of the dance character across the forehead of the mask—Sinturion (sic). It was said to be from the State of Mexico, but the town of origin was not recorded. I purchased this mask on EBay™ in 2006, from Bob Ward.

This mask is 7 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4 inches in depth. It has relief carved ears.

The carving of the mustache spilled over onto the cheeks, resembling the marks left on the road surface following a speed bump.

Both the wood and the strap show obvious staining from use.

As noted earlier the mask that follows is very unusual—a mask of Christ from the State of Mexico, complete with his crown of thorns; some of the thorns have red tips as if they have drawn blood. I was very happy to buy such a remarkable mask from Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazon in 1997. I don’t know the name of the town where this mask was danced.

This mask is 10½ inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4½ inches in depth.

The mask has a somber expression.

The back of the mask of Christ is darkly stained, particularly around the rim. This is yet another one of those masks from the Muyaes Ogazon collection that has a number on the back corresponding to its inclusion in the UNAM show of 1981 in Mexico City. Therefore this mask was collected in the 1970s or earlier.

I will conclude this post with three tin helmets that were worn during the Passion play by Centurions in the State of Mexico. I bought these from Karen Howe, who sold on EBay under the name of “LaLuna,” in 2007. Underneath the gold paint they had been painted silver. All three are missing decorative elements. For example, the first of these would have had a red brush at the top of the helmet, while the others have obvious brackets for vertical plumes. Although they have three different designs, each one has the same visor. These helmets were obviously hand made by a tinsmith.

This halmet is 12 inches long from front to back, 7 inches wide, and 12 inches tall. The other two helmets are of similar size.

I took several views of the second helmet to demonstrate the action of the visor.

In practice the visor would fall to the lower level. Obviously these visors have been designed purely for dramatic effect.

The design of the third helmet is most typical, based on current YouTube™ videos of Roman soldiers during Semana Santa performances.

Next week I will show masks from Guerrero that are remarkable because the Judas characters wear the 30 pieces of silver on their faces.