In my last post I introduced you to the telón, the curtain that surrounds a hexagonal or octagonal space. It provides a “backstage” refuge for the Huehue or Tejonero dancers, an actual stage for the male and female puppets, and finally a place from which the dance team can manipulate ropes that pull objects up and down the central pole. Here are some panels from the telón at Olintla, Puebla that I photographed in November, 2010.

This panel combines a Payaso, the Chénchere climbing to the top of the central pole, and the later ascent of the Tejón, which would have actually occurred after the woodpecker climbed to the top and came back down.

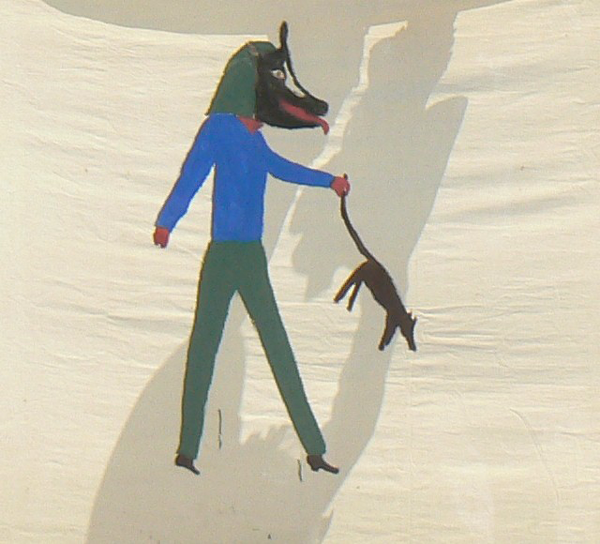

This is an interesting panel, because it portrays the perro carrying the downed Tejón, but the shadow on the cloth is that of a puppeteer, holding aloft the male and female puppets so that they appear above the curtain.

On this panel there are two Tejoneros. One has a rifle and is preparing to shoot the Tejón.

A deer runs through the forest, past an owl in a tree.

A pair of puppets gesticulate above the telón, while the Tejoneros circle outside the curtain.

A large woodpecker is being pulled up the central pole, his head drawn back to peck. The pole is hollow, so that the rope lifting the Chénchere up enters a hole at the top and comes down the interior to be pulled at the base.

This is the Tejón at Olintla, in 2010. It has a dessicated pelt. Now I will show the puppets in greater detail, beginning with the Chéncheres, or woodpeckers.

The woodpeckers vary in size, but usually they are fairly small. Here my friend and fellow researcher, Vernon Kostohryz, is holding a gigantic Chénchere that a carver made as an experiment, actually he made six of them in about 1985. His customers wanted such large birds so that they would be visible at the top of very tall poles. He has no memory of how this worked out. The extended length of this Chénchere is 28 inches.

Here is a normal sized (12 inches extended) puppet by the same carver, Roberto Villegas, next to the giant. How do these birds peck? In this view one can see that a string is attached under the chin and extends down over the front of the woodpecker. Passing through a tunnel, it emerges under the tail of the bird. If one were to hold the Chénchere in place while pulling the string where it extends under the tail, the neck would be drawn down so that the nail head on the beak would “peck” the surface. When the string was released, the neck would be pulled back to the position in the photo by the rubber band or spring that is attached behind the neck.

In this view, you can see the route of the string. It passes through a tunnel and emerges under the tail. If I pulled down the string in this photo, the beak would peck the camera lens.

This Chénchere has been fitted with some additional rigging, using the tunnels that conduct the pecking string. These additional strings, one under the neck and the other in front of the tail, provide attachment points for two lines—one that extends to the top of the pole and another that drops to the ground. By holding these lines taught, the operators can stabilize the bird. Then they can pull the other string to make the bird peck. The sequence goes as follows; the bird is hauled up a foot or two, stabilized, made to peck, and hauled further up the pole.

Here is the fully rigged Chénchere, from the side. The front and back attachment strings and the third string, for pecking, are all easily seen. This woodpecker is 12 inches long when fully extended.

Here is another Chénchere, of intermediate size—fifteen inches when extended. This one was made by Guadalupe Ortiz González, of Buenavista Puebla, in about 1995.

And here is a trio of Chéncheres, to demonstrate their normal scale. Now I will shift to a discussion of the human puppets.

Here is a pair of puppets that were carved by Roberto Villegas, the man who carved the large and small Chéncheres that you just met. They are ordinarily kept in their own wooden box, with a Chénchere; the box rests on the home altar of their owners. These puppets date to about 1975.

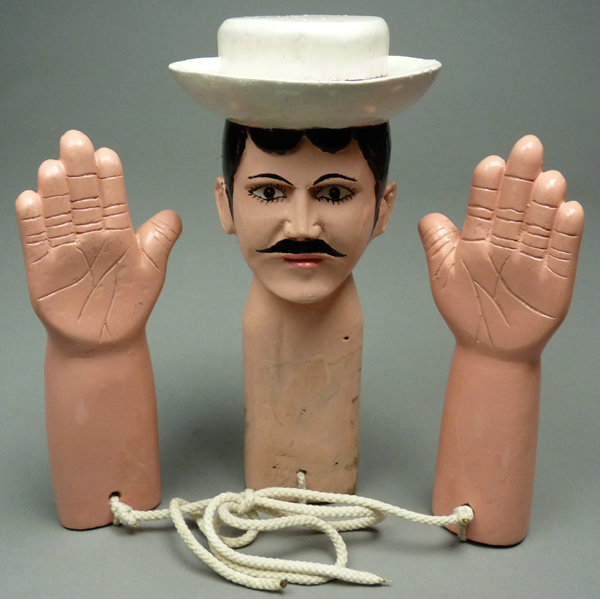

Here is San José, reduced to his parts, a torso and two arms. Note the battered condition of the fingers on his right hand.

And here are the torso and arms for the Virgin María puppet. These torsos are 7 inches tall, and the limbs are 6½ inches tall.

Here is another photo of the puppets in last week’s post that were dancing at Xonalpú. Here they are clapping their hands.

Here are the elements of the male puppet from Xonalpú.

And here is the female puppet. Both were carved by Andrés Juárez García, of Xonalpú, in 2006.

And this Chénchere, that pecked up the pole at Xonalpú, was carved by the father of Andrés, Pedro Juárez García, in about 1990. This set did not have a box. I believe that they were wrapped in a cloth.

Finally, I want to show a device that is associated with the Chénchere and that is called a guajillo. This example, from Zoatecpan Puebla, is carved in the shape of a gourd or a chili pepper, and painted in the colors of the Mexican flag. It is designed to be mounted on the top of the Huehues’ bamboo pole, the three leaves tied together with a slipknot. When the Chénchere reaches the top, yet another rope is pulled, and the guajillo falls open to release some celebratory signal, such as colored ribbons or a Mexican flag.

Next week I will introduce another subject, the “decorative masks.”