In recent posts I have presented Tejonero or Huehue masks that were carved by Benito Juárez Figueroa. Today I want to tell more about the elements of this dance.

You have already seen this photograph, taken in 2010, of Huehues dancing at the head of a procession, in Xonalpú, Puebla, a small hilltop village near Huehuetla, Puebla. The context was a fiesta honoring the Virgin of Guadalupe. In the front row, at the far left, a dancer wearing a female Huehue mask is dancing. Next to that dancer is a Payaso, or clown, wearing a conical hat, a clown’s mask, a clown suit, and dance boots (or jodhpur boots). The Female Huehue is also wearing dance boots. On the right is a Male Huehue. Behind those dancers we see another Payaso and two additional Male Huehue dancers. All of the Huehue dancers are portrayed by men. Also present are women bearing offerings, and behind them there are Negritos dancers, wearing plumed hats. In Xonalpú the Negritos no longer wear masks, but Negritos in other communities in the Sierra de Puebla still do wear masks. Recently women have been permitted to dance as Negritos. The paved street is undoubtedly recent, the result of a government program. Unpaved streets were the norm in this region until the 1980s.

After the procession, the Huehues will dance around a hexagonal or octagonal area that is enclosed by a curtain—el telón. In the middle of the enclosed area is a tall bamboo pole. The pole symbolizes the cornfields, and hosts theatrical presentations. For example, a Tejón (a Coati or some other marauding animal) runs up the pole, or more precisely, the stuffed hide of such an animal is pulled up the pole with a rope and pulley, in order to mimic the action of such a pest. The Tejoneros, being farmers, are necessarily Tejón hunters, in order to protect their crops. One of the clowns or Huehues pretends to kill the Tejón, by shooting at it with a popgun. There is a Perro (dog) character that assists the varmint hunters (the Tejoneros). The carcass falls to the ground and is carried around in triumph by one of the dancers. The painting that depicts this action in the photograph is actually on one of the panels of the telón, or curtain. At the top of the photo can be seen the bamboo pole, wrapped in banana leaves, that actually serves as the stage for these antics.

Later a Chénchere, or woodpecker, is drawn up the pole, pecking as he goes. This wooden bird has an articulated neck, so that one rope can extend his neck to peck, while a band of rubber tubing pulls it back. The Chénchere represents a mythical woodpecker who assisted a boy god, El Niño, to provide corn to humankind.

Here you can see a female clown and a Perro (dog). Note the clown’s dance boots. These dancers are wearing masks of Caucasians, but they are actually Totonac Indians. Their masks were carved by Andrés Juárez García.

In the next photograph, a female Payaso triumphantly carries the Tejón carcass. In passing, note the magnificent ear on the mask of the female clown.

The Chénchere is one of the puppets. Two more puppets, usually named San José and the Virgin María, gesticulate from behind the curtain, although they do not climb the pole. An entire chapter of my book is devoted to these puppets. In my next post I will focus on puppets. Today I will show a pair that were made by Benito Juárez Figueroa. Photos of these puppets are courtesy of Vernon Kostohryz.

Note that each puppet has a torso and two arms, united by a cloth smock. A puppeteer holds one upright arm on his thumb, the other on his two smaller fingers, and the torso on his pointer and index fingers. Manipulating these elements with his fingers, he causes the puppet to clap his or her hands.

The puppets are said to be the “Dueños” (or masters) of the dance, and I believe that they once represented pre-conquest gods, essentially forest powers or spirits.

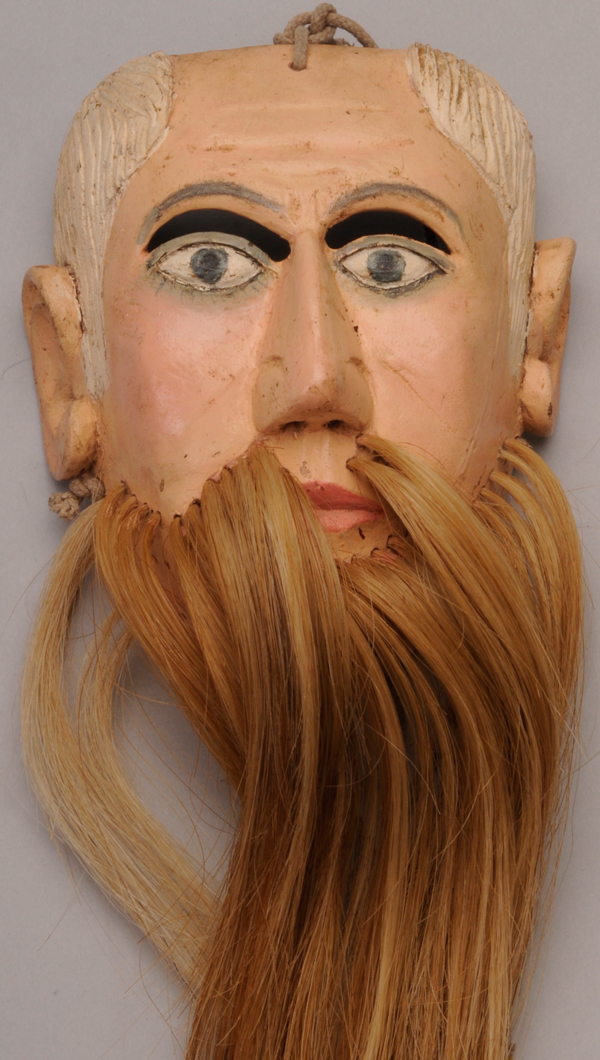

You have now met all of the active characters in the Dance of the Huehues or Tejoneros. That leaves two others whose status is ambiguous. One of these is El Viejo. This figure wears a wooden mask that has carved and painted hair, but his beard is formed from tufts of horsehair. He wears ragged clothing, and behaves in the manner of a friendly old man who is pretending to be mean and dangerous. The odd thing about this character is that he can also be called “the devil,” or Satan. I came to realize that his unexpected collection of names was an important clue about hidden aspects of this dance and its history. Many of the other dances of this region contained similar clues. I will discuss all this in a later post that will begin with a description of duality or dualism.

I don’t know whether El Viejo remains an active character in this dance, as he was not present in the performances that I witnessed in recent years. For this reason I am unable to include a dance photo that includes him. But I have had the privilege of seeing him in action, thanks to a film about the Huehues dance that was made by Bruce “Pacho” Lane, in Huehuetla, Puebla, in the late 1970s. That film, The Tree of Knowledge (originally released in 1981), is now available on a DVD (released in 2005), that is called The Tree of Life, although it actually contains three separate films—The Tree of Life (a terrific film about the Voladores or “fliers”), The Tree of Knowledge, and Democracia Indígena (an interesting film about the political tensions between Indians and Mestizos in this Totonac mountain town).

The Tree of Knowledge is a wonderful film, well worth obtaining, because it shows so much about the Huehues dance, including the installation of the telón and the bamboo pole, the ascent of the Chénchere, the ascent and mock shooting of the Tejón, and of course some of the antics of the Viejo. You can buy the DVD (The Tree of Life) directly from Ethnoscope (the film maker’s website): http://www.docfilm.com/webpages/Mexico/trOfLife.html

I do have photos of a Viejo mask from the Dance of the Huehues.

This mask was identified by its carver, Roberto Villegas Santiago, as a Viejo mask from the Danza de los Huehues.

In the side view, one can the characteristic ear design of Roberto Villegas Santiago.

The back of the Viejo mask shows only mild wear and the hair had been lost, although this was recently restored after the mask was collected. This pattern of disuse is consistent with my observation that this character is no longer an active part of the Huehue dance.

There is a second ambiguous character to discuss, el Pájaro. I have no published description of a character in the Huehues dance wearing a bird’s mask, but Vernon Kostohryz and Carlos Moreno Vásquez found such a mask, said to have been carved in about 1975, in Tuxtla, Puebla. I will include it here.

This is the Pájaro mask from Tuxtla. Does it represent a cornfield marauder? Is it a woodpecker? Did it dance in Carnaval? I just don’t know.

As you can see it has excellent wear, with differential staining.

Next week I will tell you more about the puppets.