This series of posts about Yoeme (Yaqui) Pascola masks began on July 4, 2016.

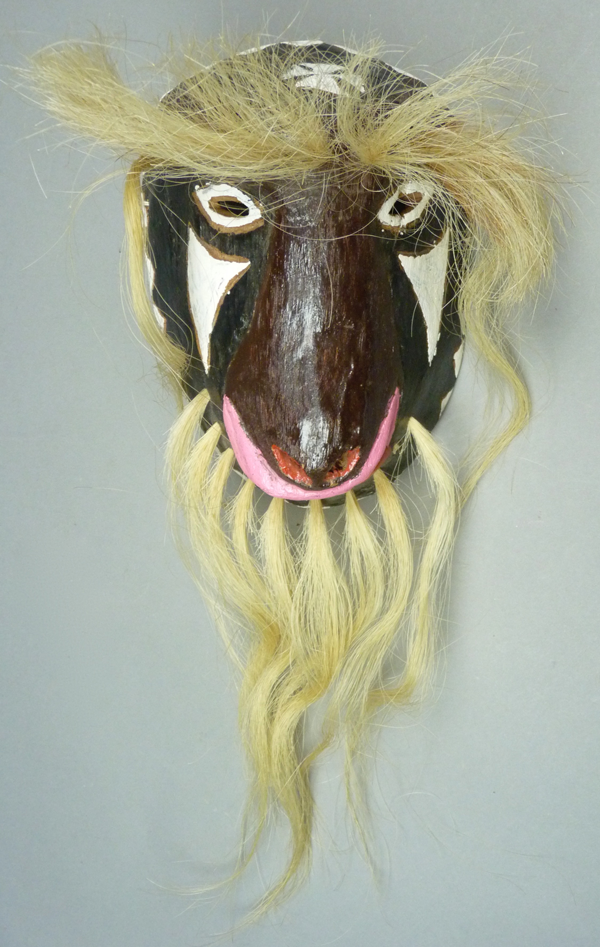

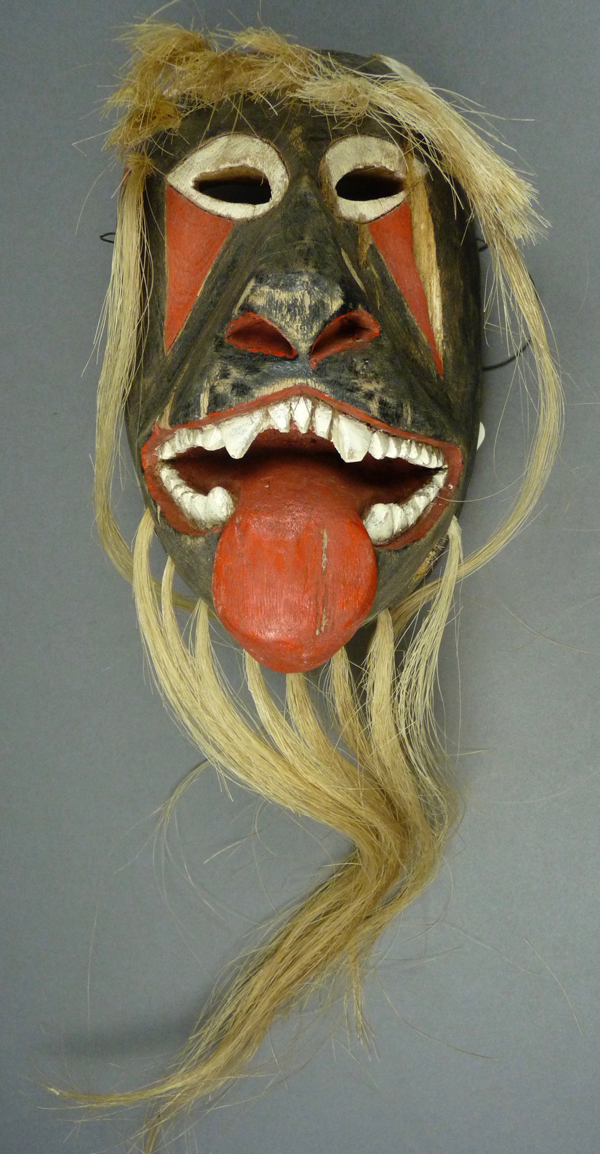

In 1990 I purchased a wonderful Yaqui Pascola mask with the face of a Chango (an ape or monkey) from Robin and Barbara Cleaver. As was frequently the case, this mask came up from Mexico at that time with little history. There was a similar mask in the collection of James Griffith, and he had included it in the book that he wrote with Felipe Molina—Old Men of the Fiesta: An Introduction to the Pascola Arts (1980, page 23, fig. 10 right). That mask too lacked an identified carver, but Griffith did state that it dated to the early 1970’s. I didn’t meet Tom Kolaz until about one year later; he told me that both masks were the work of Manuel Centella Escalante. I later realized that a handsome Goat pascola mask from about 1960, which was in the same photo as Griffith’s Chango mask, had also been carved by Manuel Centella. Two things became apparent in the years that followed—that there were many more unidentified Manuel Centella masks in private and museum collections, and that this relatively unknown carver was one of the most brilliant Yaqui artists of the mid-20th century. In this post and several more to follow I will celebrate his work. Today I will show a series of Chango masks by Manuel.

I share the impression of James Griffith that this carver may well have been the inventor of these Chango masks. He was certainly the one who created a number of them during a period when they were popular, sometime in the 1960s or 70s. They had their moment, but since then human faced masks and canine masks have been most commonly chosen by dancers. One of the more reliable distinguishing factors for this carver is this forehead cross, which consists of four triangles with their points together. Often there is a chin cross of the same design, but we shall not see this on the majority of the Chango masks.