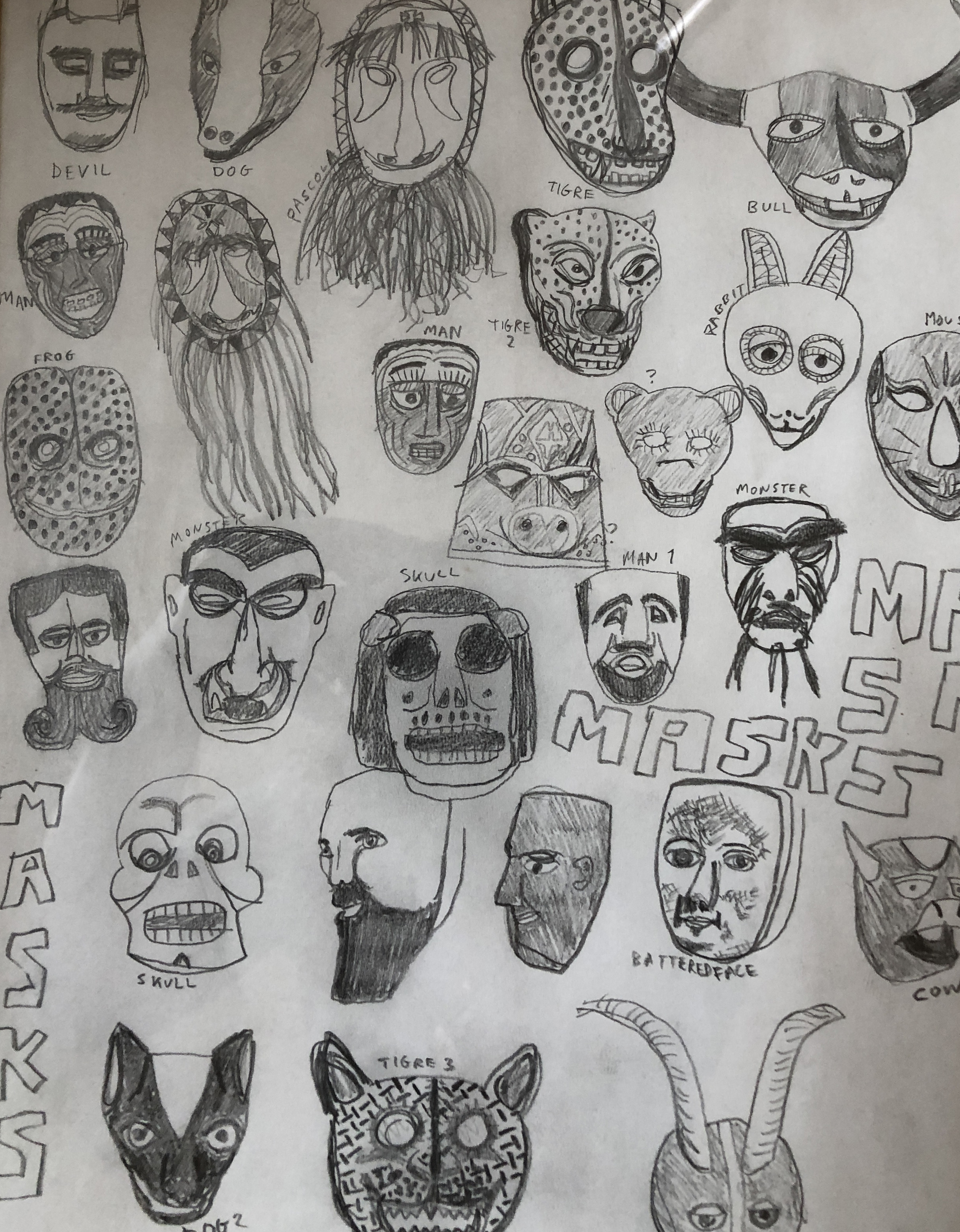

Last week I discussed the use of “models” by mask carvers in the Sierra de Puebla, explaining that when a carver wished to make a mask in an unfamiliar style he might commonly use the style of another carver as his point of departure. Today I will provide another example that I particularly like because it involves one great master borrowing from another. This example was initially presented in my Masks and Puppets book on pages 168 and 169, but described in very small print.

We might begin with material presented in Chapter 5 of my book—”The Process of Looking at Masks.” There I explained how one could look for tell-tale details in a mask to determine the probable carver, but also taking into account that a carver’s style might change in a subtle way over the many years of his carving career. I illustrated these two points by comparing four Hormega ( a variant of Santiaguero) masks that were carved by one of my favorite carvers, Benito Juárez Figeroa, whose carving career spanned many decades, from about the age of 18 until his death in 1994, at the age of 84. I devoted pages 132 to 141 to his other masks, along with some that were carved by his relatives. On December 1, 2014 I published a post about these Hormega Masks by Benito; by then I had five of them. Here is that link.

https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=1640#more-1640

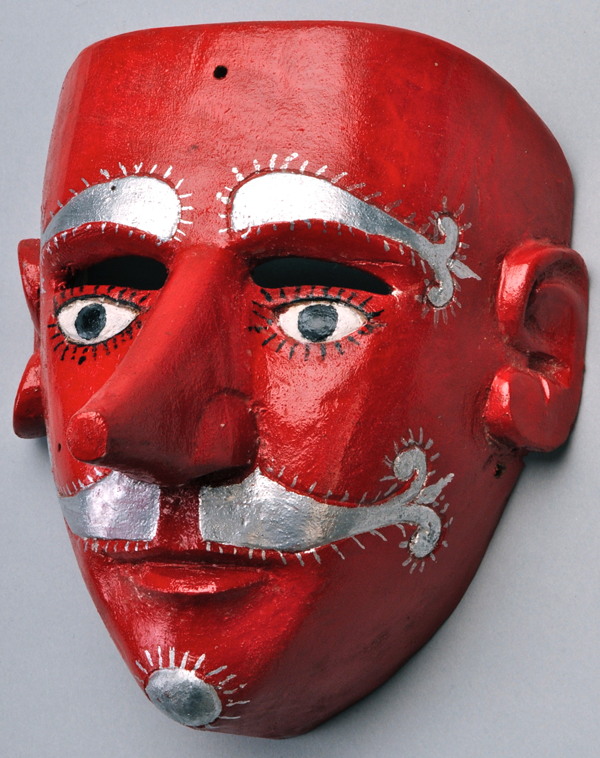

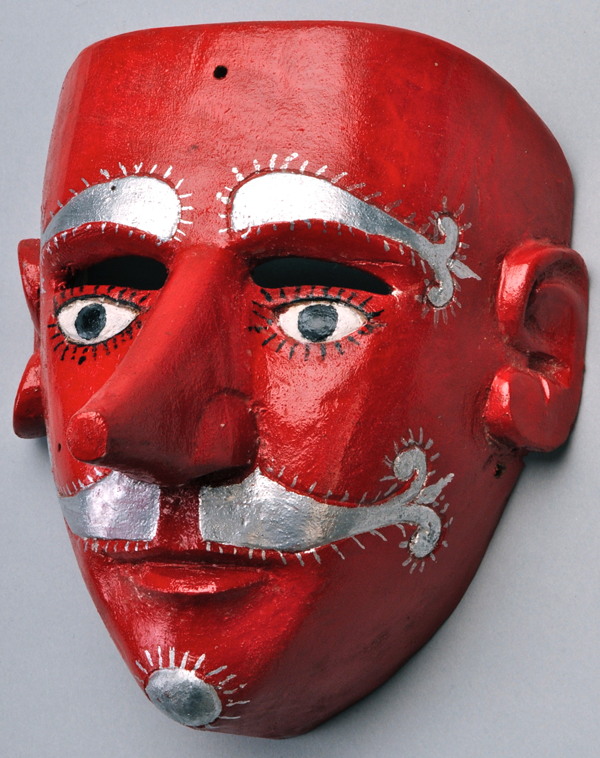

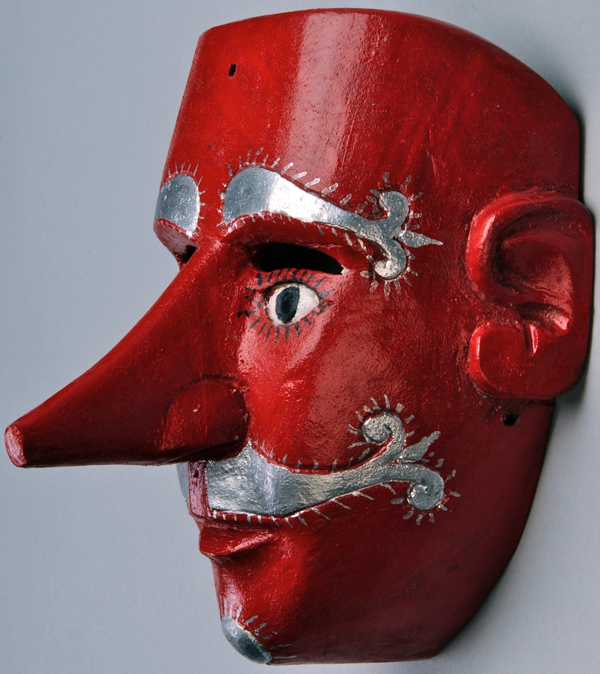

We don’t need to go beyond the first mask in that link, which I judged to be the oldest, to see the style that another master, Roberto Villegas Santiago, used as a model. Here is a side view of that mask from my collection.

Roberto and Benito had been friends, and I suspect that Roberto might have obtained his similar mask directly from Benito.

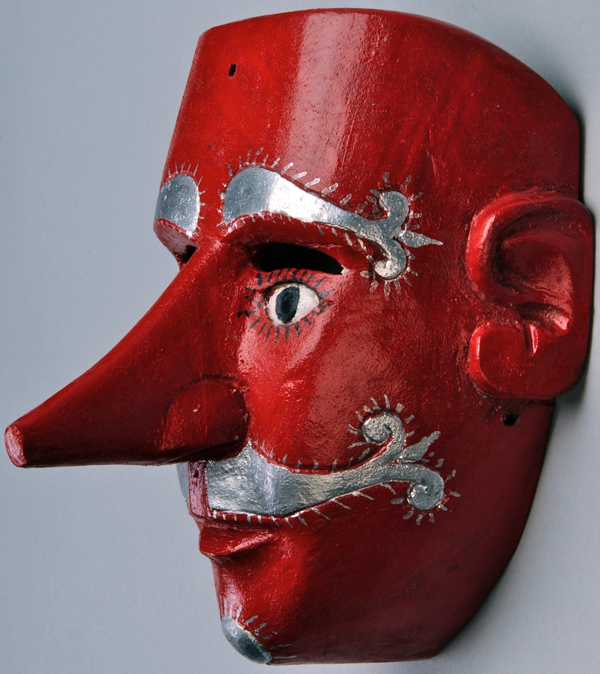

For comparison, here are side views of the model and the mask that Roberto Villegas Santiago was in the process of creating.

He is just roughing out the shape of this mask.

Two details were of particular interest to me:

1. Roberto made his friend’s design, but added on carved ears in his own traditional style. Benito’s Hormega masks did not come with ears.

2. Roberto chose to carve the mustache and eyebrows in low relief. For such curling mustaches and other elements, Benito usually simply painted these features.

Here is an additional interesting feature. Many mask carvers in Mexico begin the carving process by roughly shaping a log with a machete and then switching to chisels to create the details. Master carvers sometimes mark out measurements and saw the wood to a preliminary shape, which they call a “blank.” This is such a blank. It is nearly ready to be shaped by chisels .

In this photo Roberto is standing at a wooden workbench that he had long ago constructed for himself. He had also made his own table saw, mounting an electric motor and armature onto a similar wooden frame. The blank was at least partially cut out on his table saw, as were the smaller pieces of wood in this photo. In this view, Robert is demonstrating that he intends to glue these wooden blanks to the faces of the blanks, to permit him enough thickness to carve such long noses. You may be able to see, in the earlier photos, that Benito had done the same.

I attempted to buy one of the masks that Roberto was making on this day, but he explained that he was filling an order from an Hormegas Dance troupe for 8 masks, and so all of these were already promised. He said that I could order one for myself, but that it would be some time before he could fill that order.

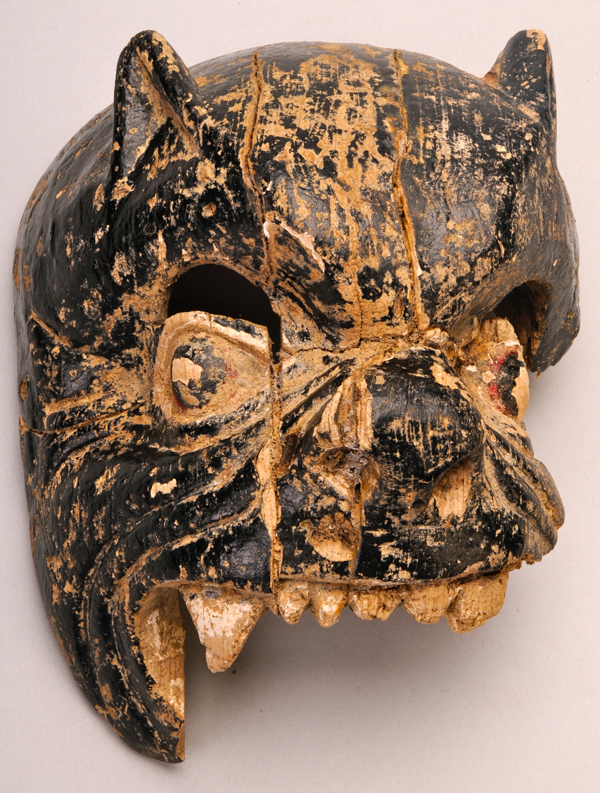

One year later I received the mask that I ordered from Roberto.

The back has been smoothed with a chisel but the mask has never been danced.

Next Week- I plan to recycle some of the earliest posts that explained about Decorative masks, because over the intervening years many readers have sent in photos of such masks, wondering if they were traditional.

Bryan Stevens