In April 2006 I had the great pleasure of traveling with a group from the Arizona State Museum, in Tucson, to the Rio Mayo villages in Sonora to observe Easter celebrations by the Mayo Indians there. We were led by Diane Dittemore, a curator at the Arizona State Museum, with the assistance of Emiliano Gallega Murrieta, an ASM Intern who had grown up in Sonora. We visited Leonardo Valdez, who had established a Museo in Etchohoa to display his collection of Mayo Fiesta regalia. By coincidence, we ran into Bill and Heidi LeVasseur there; they later established a mask museum in San Miguel D’Allende, and Bill’s book followed to catalogue their museum collection—Another Face of Mexico (Art Guild Press, Santa Fe New Mexico, 2014).

The group encountered a number of Mayo Pascola dancers, and we saw some attractive masks being danced, but it seemed that those were not available for sale at that time, and perhaps they were already promised to Leonardo Valdez. Then again, it is also my impression that danced masks are frequently not sold in the exciting time surrounding a fiesta, particularly if the dancer is using his favorite mask. Later, when the dancer wishes to raise cash, he may sell a mask that is no longer wanted.

We also visited with several mascareros (mask carvers) and they did sometimes have new and undanced masks to sell. This leads me to the subject of “made-for-sale masks.” Popular carvers are often asked by Pascola dancers to make masks to order, with particular desired features and sized to suit that dancer. However, in the absence of such orders the carver may elect to produce masks that he hopes to sell to some future customer. These made-for-sale masks may reflect local traditional design preferences or not. Ultimately they will prove to be either suitable or unsuitable for use by the average Pascola dancer, depending on the mask’s details and the dancer’s preferences. The suitable masks are meant to interest dancers as well as tourists or collectors, while the unsuitable ones are obviously produced for the latter groups and not for traditional use. Thus the term made-for sale is not inherently indicative of whether a mask is faithful to local traditions or not. In today’s post we will look at a pair of made-for-sale masks.

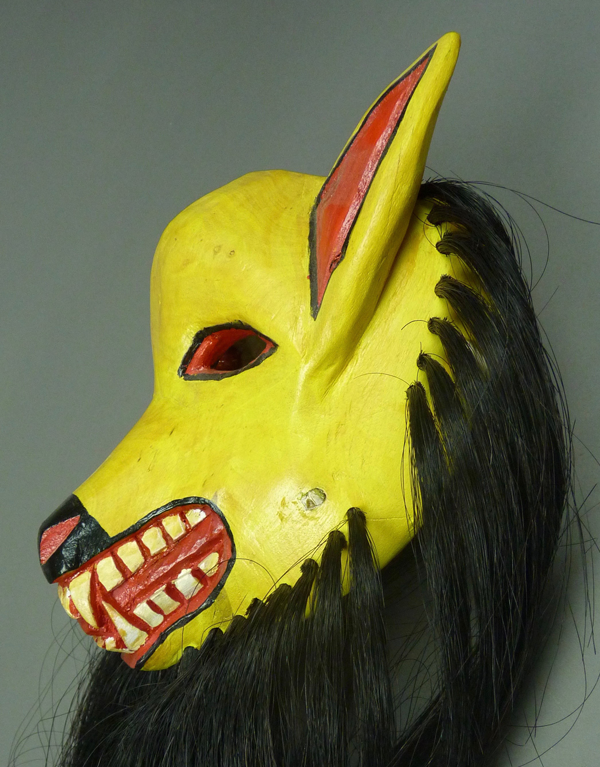

I bought this first mask from Arnulfo Yocupicio when we visited him at his workshop, in Masiaca, Sonora. I don’t know whether Arnulfo is related to Manuel Yocupicio. He carves traditional human faced Pascola masks that are painted black, along with others of dogs or wolves. Here is one of those wolf masks. Although such canine masks are popular among Yaqui Pascola dancers, one only occasionally sees danced Mayo examples.

This mask has very long (and carefully applied) hair, a trait that Rio Mayo carvers had recently copied from the Rio Fuerte Mayo style in Sinaloa.

This mask was probably made for the purpose of sale to tourists, yet it is elaborately made and carefully carved, and could certainly be used by a Rio Mayo Pascola dancer.

There is no forehead cross, and Arnulfo explained that a cross was unnecessary on these animal masks because they were unlikely to be danced.

This is a fierce expression.

The mask itself measures 9 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4½ inches deep. Including the long beard it is 36 inches tall.

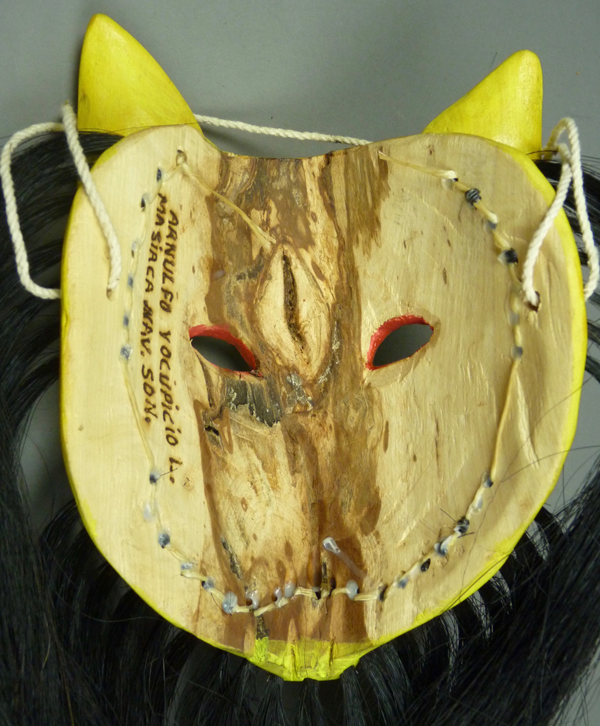

Arnulfo signed this mask on the back with a wood-burning tool. The back obviously lacks staining from use.

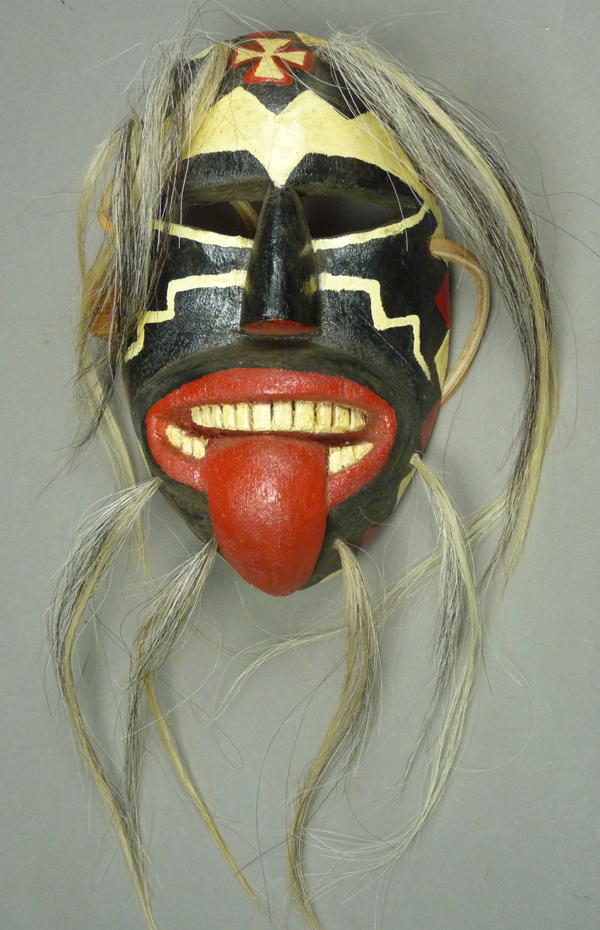

A Mayo man from the village of Tres Cruces (three crosses), Sonora approached me on the street, offering to sell me a mask. I failed to record his name. Here is this mask. The painted designs on the cheeks suggest that it depicts an “Apache” Indian, a theme we have encountered on Yaqui Pascola masks.

This mask is very well carved and carefully painted. There is a forehead cross in the Maltese design. There is a painted rim design in a familiar style.

There is just one aspect of this mask that is not up to the usual community standard—the hair bundles are small and there are too few of them. This alone suggests that the mask was carved for sale to a tourist, and not intended for a dancer. Yet it is otherwise excellent.

This mask causes one to recognize that although made-for-sale masks sometimes seem inferior to those used by dancers, the variation in quality may not reflect the carver’s skill level. If carving lower priced masks for the tourist market, the mask maker may deliberately choose to cut corners, to do less. Or a carver may produce masks to an acceptable community standard at a certain price point, but provide enhanced quality or features on a custom basis. In a future post I will show masks by a Mayo carver like that, Hector Francisco Gamez.

I have always been charmed by the masks of Antonio Bacasewa, a Yaqui carver from Vicam, Sonora, whose masks were all carved to one respectable quality standard, and they were invariably provided with better than average hair. Here is a link to my initial post about Antonio on July 25, 2016.

https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=6578#more-6578

The next link leads to three more posts about masks carved by Antonio Bacasewa (on August 1, 8, and 15, 2016).

https://mexicandancemasks.com/?m=201608

This mask is 8 inches tall, 5 inches wide, but just two inches deep, from the back edge of the rim to the tip of the nose. The hollow back of the mask is very shallow—one inch!

The back has been carefully carved and the surface smoothly sanded, but yet the mask seems too shallow to accommodate a dancer’s face. Perhaps a child could wear this mask? I don’t know whether this mask was carved for a young traditional dancer or for sale to a tourist, although I suspect the latter. Note that the hair bundles are not sewn in place from the back, but held in drilled holes by pegs or glue (no pegs are visible).

Next week we will examine an anonymous Rio Mayo Pascola mask with a spotted face.

Bryan Stevens