Following the conquest of Mexico by Cortez and his conquistadors, Roman Catholic missionaries arrived with the charge to convert the Indians to Christianity. Because these Indians had traditionally used masks, costumes, music, and dramatic performances to portray their gods and beliefs, it seemed obvious that such theatrical practices could be used to teach them about European religion, so plays that had long served to convey and reinforce Christian teachings in Spain and other European nations were adapted by the missionaries for use in New Spain. Of these, the most famous are La Pastorela (the Shepherd’s Play) and Los Moros y Cristianos (the drama of the Moors and Christians). I have told quite a it about the latter play in earlier posts, particularly noting how this became the model for other dance dramas, such as the Santiagueros. Today I will introduce a series of posts about the Shepherd’s Play.

In my post of Aug 11, 2014, I had shared with you some images of a Diablo mask that was used to portray Satan in a Michoacán performance of the Shepherd’s play. My purpose then was to illustrate a remarkable fact—Mexican Masks, Donald Cordry ‘s famous book, contains a curious mixture of inauthentic (decorative) masks and extremely important authentic masks and related dance photos. Today we will revisit that terrific Diablo mask, which is one of my favorites, and compare it to dance images provided in Cordry’s book to introduce the Pastorela dance. Here is this Diablo that I first showed you nearly three years ago.

Spencer Throckmorton, an ethnographic arts dealer in Manhattan, is particularly fond of devil masks, and he once devoted an entire wall of his apartment to their display. In 1995 he sold those masks, and I purchased this beautiful old Diablo from his wall. It was originally collected near Lake Patzquaro, in Michoacán. It had four holes around the forehead, the central pair were each 3/8” in diameter; I wondered about the purpose of those holes. Paging through Cordry’s book, I found photos (Plate 7 on page 6 and plate 307 on page 247), which included a mask that resembled and explained my mask, and it even appeared to be by the same hand. Those photos were taken by Donald Cordry in Cherán, Michoacán, in 1935. The mask in the photos had curved wooden horns projecting from holes on the sides, along with carved snakes writhing across the forehead.

From the side, one sees that the hole for the horn is plugged, or perhaps that horn was sawn off, nearly level with the face.

This mask has a dramatic angular face. The paint is old and cracked.

From above, this face has a complex series of wrinkles and folds. The holes that were apparently once the attachment points for snakes are more easily seen in this view.

From below, there is a hollow spot under the elongated chin.

This mask is 10 inches tall, 6 inches wide, and 4½ inches deep.

The backs of older masks from Michoacán often have this grooved appearance. There is obvious staining from use. Under the left eye, someone noted the place of collection, Lake Patzquaro. Given its close similarity to the mask in the Cordry photographs, we can assume that this mask dates to the 1930s.

Those Cordry photos also show some of the other characters in the Pastorela performance, including a Diablo with the face of a bull and an Hermitaño (pronounced air-mi- tawn-yo), a friar or religious hermit like the European religious mystics from the Middle Ages, such as Saint Francis of Assisi. In Michoacán and Guanajuato one finds a rich variety of animal devil masks for use in the Pastorela dance, while the Hermit masks are particularly well liked in Michoacán, to the point that some villages feature large groups of dancers wearing hermit masks. One does also find masks for the Shepherd’s Play in isolated pockets in other Mexican states, such as those from Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco. In a later post I will show a set of masks from that place. In contrast, devil and animal devil masks from other states, such as Guerrero, are used in other dances devoted to moral teachings. I told about such performances and masks in posts from September 29 (https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=1074#more-1074) and October 6, 2014 (https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=1214#more-1214).

The Pastorela dance is one associated with Christmas. Indeed, Christian churches in the United States have a tradition of performing what we might call an abbreviated version of the Shepherd’s play on Christmas Eve, in which Shepherds file to the front of the church to pay homage to an infant or image in a cradle. Prominently absent from these American versions are the Diablos, who represent the seven deadly sins that tempt humankind. I thought that I should introduce you to this performance early, so that you could be aware in advance of the opportunity to witness this living tradition in Mexico, this December.

Next I will show another devil from Spencer Throckmorton’s collection that I bought in 1995; he said that this one, an animal diablo, was one of his favorite masks. According to the tag, it was collected in the field in 1947, in Michoacán. There is a duplicate of this mask on page 51 (plate 45) of Moya Rubio’s Máscaras: La Otra Cara de México/ Masks: the Other Face of Mexico (third edition, 1986, the first bilingual edition). That author believed that his mask was from Guerrero. There is a near duplicate of this mask in the book by Estela Ogazon, with the hidden co-authorship of Jaled Muyaes—Mascaras—plate 3, which is listed as a Pastorela Diablo from Guanajuato. This sort of difference is not actually a contradiction, because the communities on the two sides of the border between Michoacán and Guanajuato are not very far apart and the Pastorela dance is popular on both sides in the same region, so that masks undoubtedly pass back and forth between the two sides. On the other hand, I believe that the Moya Rubio mask was actually made and danced in one of these two states, rather than Guerrero. Of the three examples, this one from Spencer Throckmorton appears to be far older and more worn that the other two. Although collected in 1947, it has staining from use to suggest that it was already danced for about about 20 years at that time, and therefore dates to the 1920s.

The snakes that extend from the chin to circle the eyes are carved in relief, as are the tongue and the teeth. In other words, none of these elements were carved separately and then applied to the mask. On the other hand, the horns (from a cow), the leather ears, and the round mirrors that depict the eyes are all applied. Such relief carved snakes are very typical on the animal devil masks from Michoacán and Guanajuato.

In this instance, the animal appears to have a canine face, like that of a coyote. Moya Rubio actually called his near duplicate mask a coyote.

The nose is long and slender.

The upper jaw has been carefully hollowed.

This wooden mask measures 11 inches tall, 7 inches wide, and 8 inches deep, without the horns. With the horns it measures 4 inches taller and 3 inches wider.

The back of this mask reveals heavy staining from use, as if it were danced for about 20 years or more. There is a carved opening between the left edge of the tongue and the left corner of the mouth to permit air exchange at that level, but there is no corresponding hole on the right side. There are old leather ears. The string (strap) is recent. This heavy mask requires a strong hanging wire, which I removed for this photo.

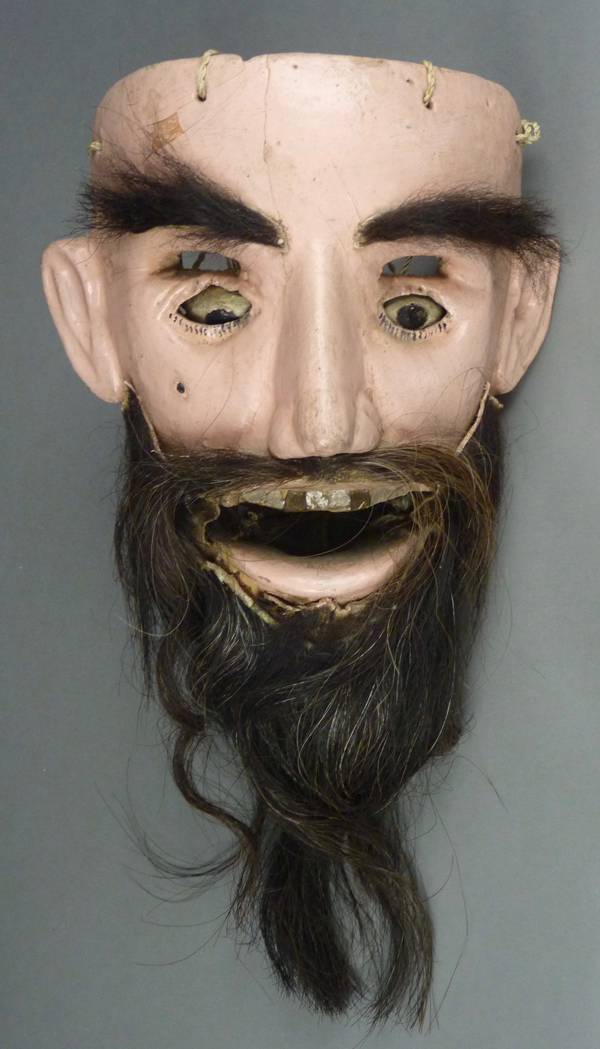

Since I have been showing you rather old masks that have duplicates in other collections, I will end this introductory post with a spectacular Hermitaño that also straddles the border between Michoacán and Guanajuato. Mine was said to have been collected in Salamanca, Guanajuato. In 1988, Barbara Cleaver helped me to buy this mask from Robert Lauter, a famous Los Angeles dealer and collector; he had purchased it from Robert Brady, an even more famous collector. There is a near duplicate in the Mascaras book by Estela Ogazon (plate 30) that was reportedly collected in Puruándiro, Michoacán. Those two towns are 100 kilometers (70 miles) apart. Here is my mask from Salamanca.

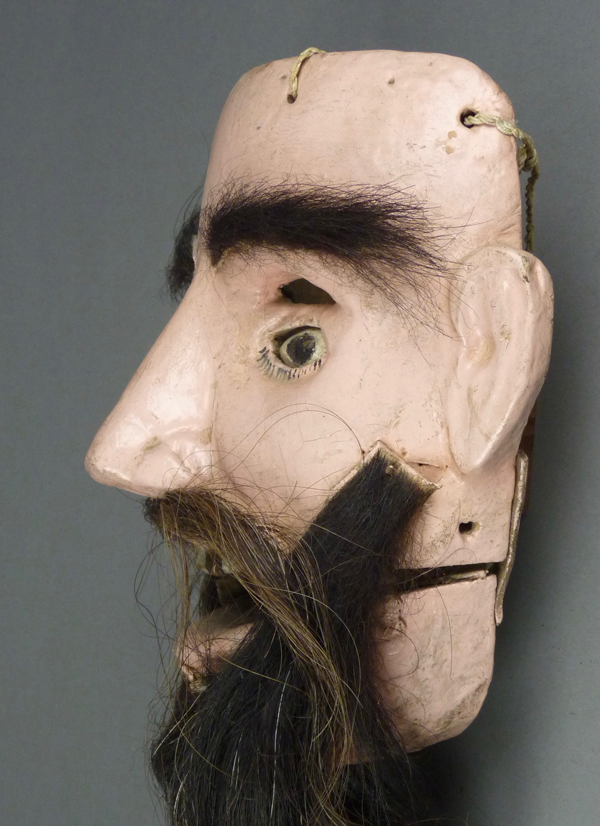

The eyes are movable. They are meant to be attached to the articulated (movable) jaw by strips of rubber, so that when the jaw opens, then the eyes roll down. The vision slits are above these movable eyes. The eyebrows, mustache, and beard are indicated by attached pieces of hide. The teeth are covered with either foil or brass.

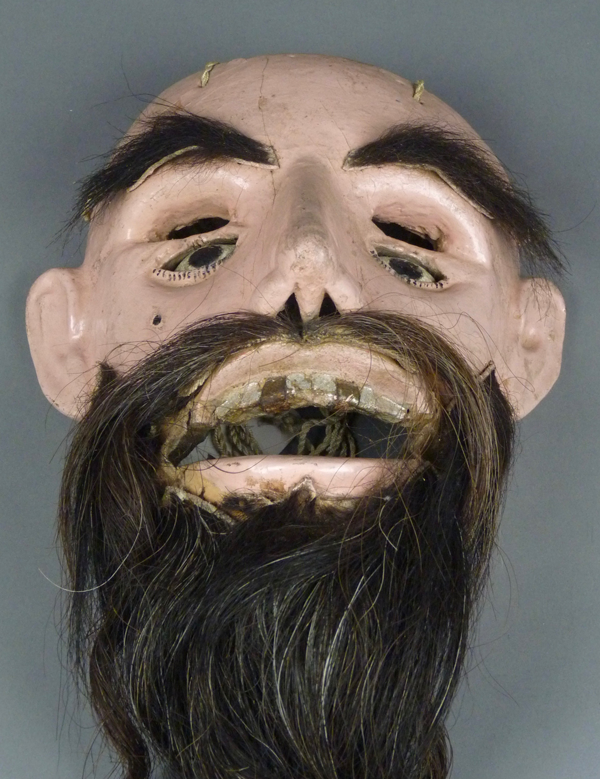

Both eyes should roll down when the jaw opens, but the left eye (on the viewer’s right) sticks, and the rubber to connect the eyes with the jaw has deteriorated. This photo provides a view of the sort of animation that the mask was meant to provide when it was new and intact.

The quality of carving is typical of the mid-20th century. A leather hinge on the back of the mask allows the jaw to sag.

In this view the mouth is wide open.

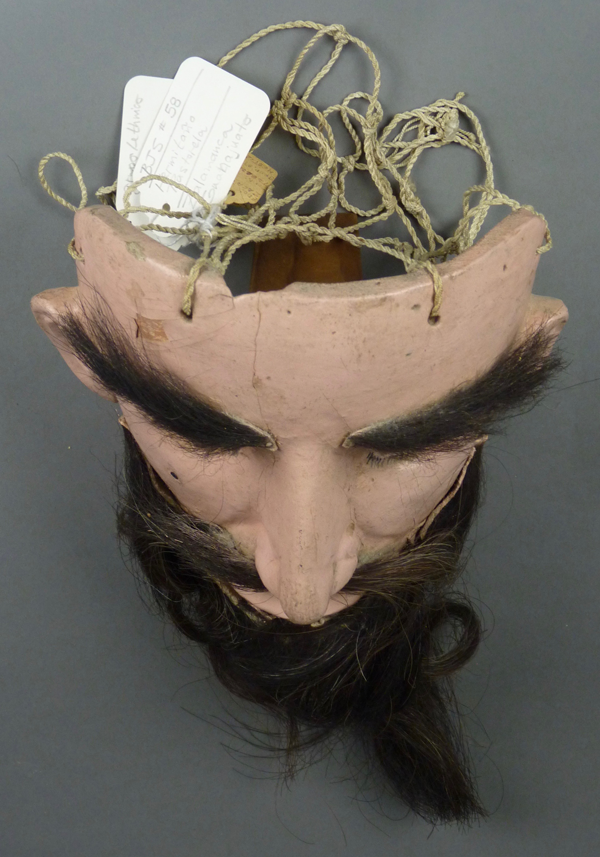

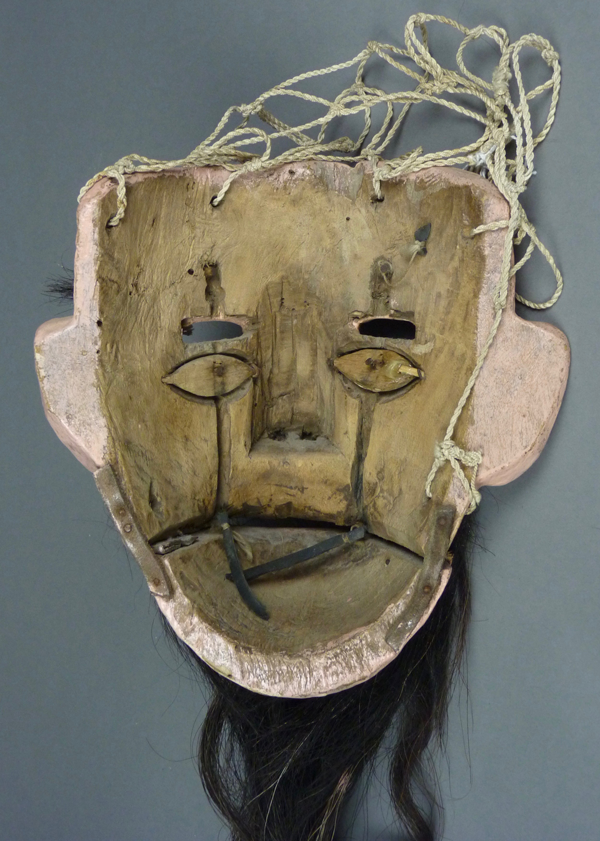

This mask has a net of string instead of a simple strap. It is 8¾ inches tall, 8 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep, not including the beard, which extends another 7 inches below the tip of the jaw.

The back is moderately stained from use. The rubber strips (cut from recycled inner tubes) run in carved grooves from the lower jaw to attachment points above the vision slits. One end of the right eye has a repair. That eye rotates as it should. The left eye, although original and intact, doesn’t roll easily. The leather straps that hinge the lower jaw to the mask are easily seen from this view.

Next week I will continue to discuss masks from the Pastorela dance.