In the last two posts we have examined Fariseo masks from San Luis Potosí, such as skulls, demons, and devils, that were obvious representations of negative figures. But I threw in a bishop (Obispo), to include a potentially positive figure who had evidently turned bad. As Janet Esser pointed out in her doctoral thesis, Winter Ceremonial Masks of the Tarascan Sierra, Michoacan, Mexico, there is an obvious theme in Mexican Indian dance dramas of good versus bad or beautiful versus ugly. One can also find this expressed in terms of insider versus outsider, normal versus deviant, or wise versus ignorant. Dances featuring such dichotomies appear to have the purpose of moral teaching, essentially illustrating culturally defined behavioral choices, but sometimes through the use of stereotypes that have nothing to do with choice, because they reflect ethnicity, nationality, victimization, mental illness or intellectual limitations. Stereotyping through such labels is becoming increasingly less acceptable in North America, although it was common in the past, when such images had been incorporated in this dance. Today’s post will feature masks that raise such issues, while those in next week’s post will present another group of masks with ambiguous meanings that are likely to have been associated with ignorance and associated impulsive behaviors. This is an arbitrary division on my part, to manage such a variety of masks that must all be ultimately meant to represent negative figures, in this dance context (portraying the enemies of Christ during Semana Santa).

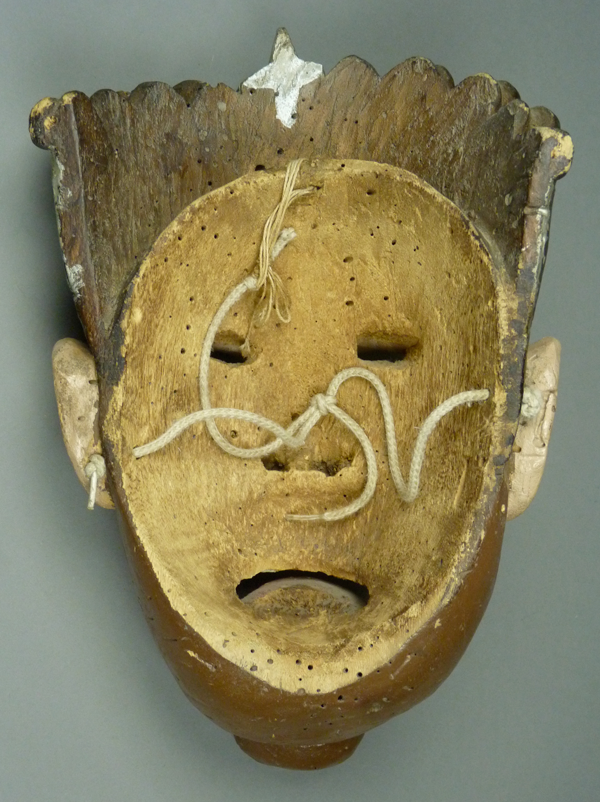

Here is a mask of a Rey (king).

His expression is unfriendly, as if he is a malevolent figure—an evil king. On the other hand, he is wonderfully carved. There is a cross or star on his crown.

This mask is 14 inches tall, 9 inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

Note how the crown is hollowed out above the space for the face. There is as clear pattern of differential wear. Like many masks from this region, the wood has pin holes that probably reflect the use by the carver of wood that had been previously infested by wood-boring insects. The features of such masks may or may not be damaged by such insects.

I purchased this king mask from Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazón in 2000. Jaled recalled that they had encountered a group of Fariseos in a cemetary in San Vicente, San Luis Potosí, during the celebration for All Souls Day. He emphasized that the Fariseos do not characteristically dance at that time, but that these dancers had visited the cemetery to honor a deceased member of their group. There were dancers wearing masks of a king and a queen; Jaled attempted to buy both, but the owner of the queen mask was unwilling to sell. He showed me a photograph that he had taken of the group. I felt very privileged to buy the king.

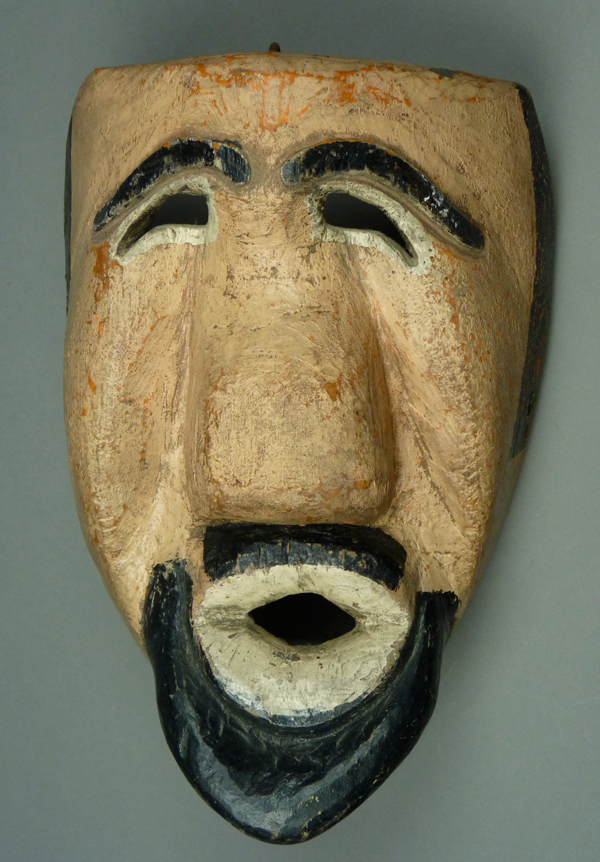

I got the next mask from René Bustamante, a mask collector and dealer from Oaxaca, in 1993. René reported that this mask represented “El Profesor,” a character that had danced during Carnaval. It was found in Tancanhuitz, a village near Ciudad Santos, San Luis Potosí. I believe that most of these large masks were fariseos that were primarily used during Semana Santa, but there was always the option to use them during Carnaval, as well. I particularly like the eyes of this mask, framed by relief carved eyelids.

This mask is 9 inches tall, 7 inches wide, and 5 inches deep.

This is an old heavily used mask. René estimated that it dated to the 1940s.

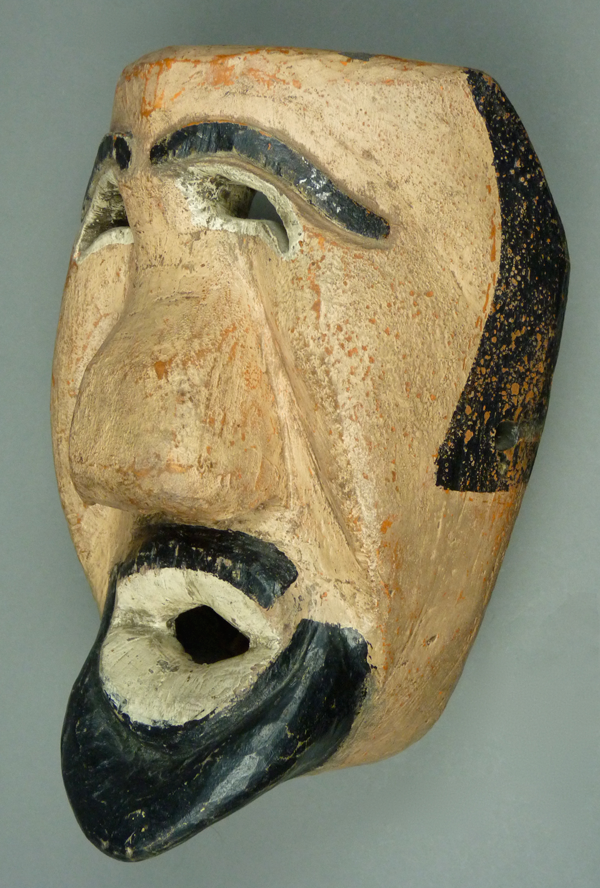

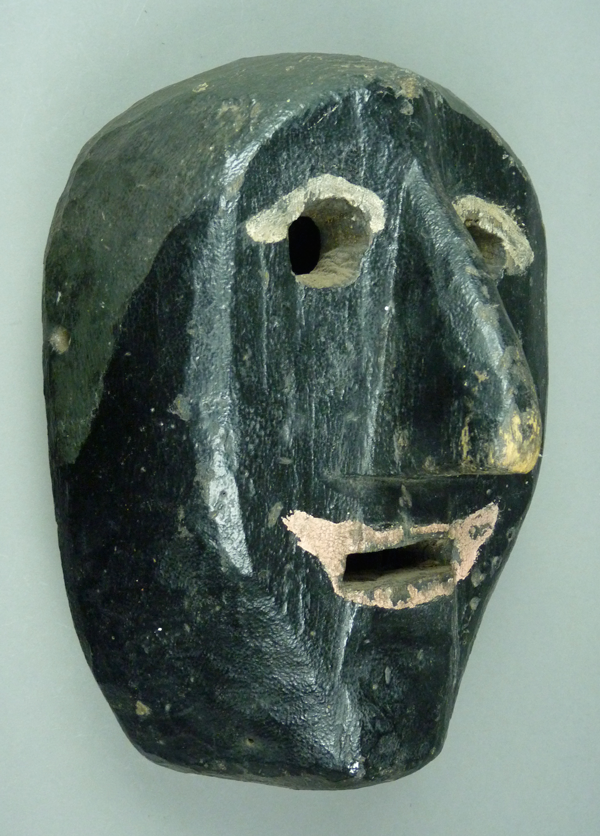

The next mask, obtained from René Bustamante in 1995, was found in Rancho Santa Catarina; René called it Profesor Chango (Professor Monkey). On inspection, this appears to be a rather bloody professor or monkey. The cross on his forehead suggests his involvement in Holy Week (Semana Santa), rather than Carnaval. “How so?” you might ask. Those dancers who participate in dramas about Easter are usually devout Christians, even though they are depicting the persecutors of Christ in the performance. A cross on the mask or a crucifix around the neck allow the dancer to demonstrate his loyalty to God, despite his role. Note that the King mask has a prominent cross. I show this mask after the Profesor to contrast a benign looking figure with another who projects a violent and potentially malignant appearance; they may well have danced side by side.

Whatever the meaning of this paint, I savor its vivid appearance! The cleft chin or beard was deliberately carved.

This mask is 9 inches tall, 6½ inches wide, and 3¼ inches deep.

This mask has typical differential staining, although this may seem subtle in the photo. René also estimated that this mask was from the 1940s. Note the strap made from a strip cut from an inner tube.

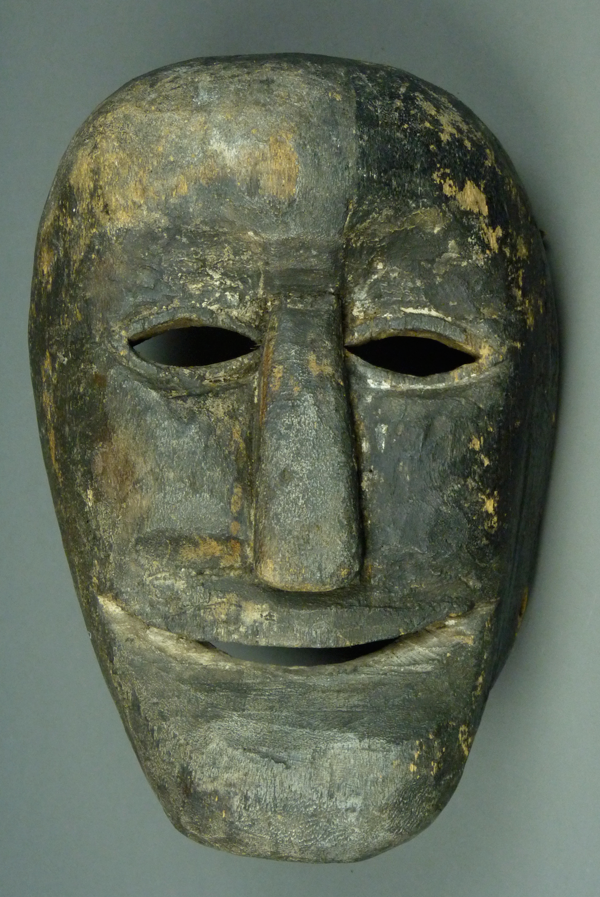

The next mask, also from René, has a wonderfully primitive appearance; I particularly like his smile. He came with little information. In form he is a Viejo (old man). He has the same large size as the other Fariseos from SLP (San Luis Potosí).

This mask is 10 inches tall, 8 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

I like the eyes, the nose, and particularly the mouth. The patina is also notable.

The rim of this Viejo is very darkly stained, reflecting many years of use.

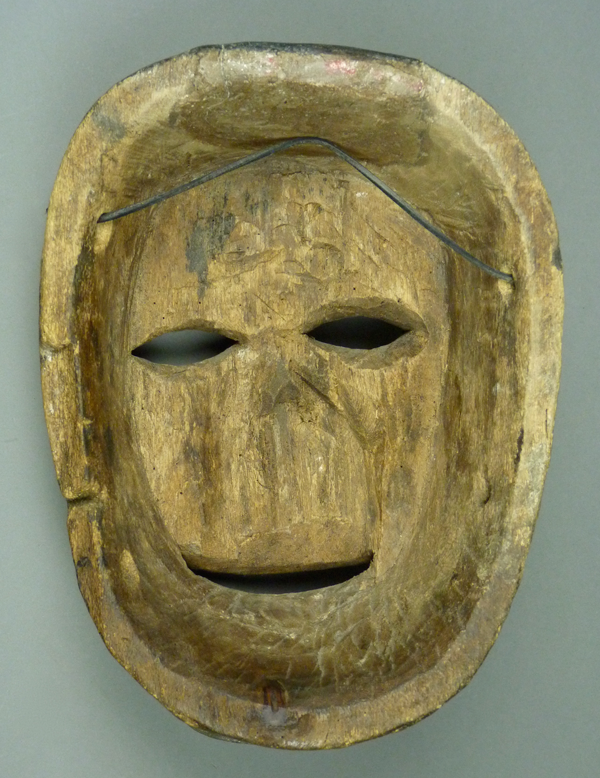

Although I bought this next very primitive old Viejo from René Bustamante in 1993, it was originally collected in the field by Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazón. I know this because there is a number painted on the back (738) to mark its order in the UNAM Máscaras show of 1981.

This mask is 10½ inches tall, 7½ inches wide, and 5½ inches deep. It has an impressive appearance due to its large size, like a Juanegro mask on steroids. Note how the carver used a saw to define the shape of the nose and then extended the saw cut to define the borders of the chin.

Due to its size and patina, this mask gives the dancer an eerie appearance—big headed, ancient, and forbidding—as if an ogre.

The staining from wear is dramatic. This was 938 in the UNAM show.

René Bustamante dubbed this next large mask “El Feo” (the chief feo). It was found in Tancanhuitz, SLP. I bought it in 1995. Feo means ugly, and is used as a reference to the behavior of the wearer, a clown who is capable of dramatically impolite, intrusive, and bawdy behavior. He has a clown’s mouth. Imagine your response if he began to move in your direction; I for one would not be amused! In general, a Feo’s behavior demonstrates the opposite of ideal behavior—what not to do. The Fariseos would probably all be considered Feos.

The holes made by insects in this mask are particularly prominent.

This mask is 11 inches tall, 7½ inches wide, and 6½ inches deep.

The Feo mask is extremely deep.

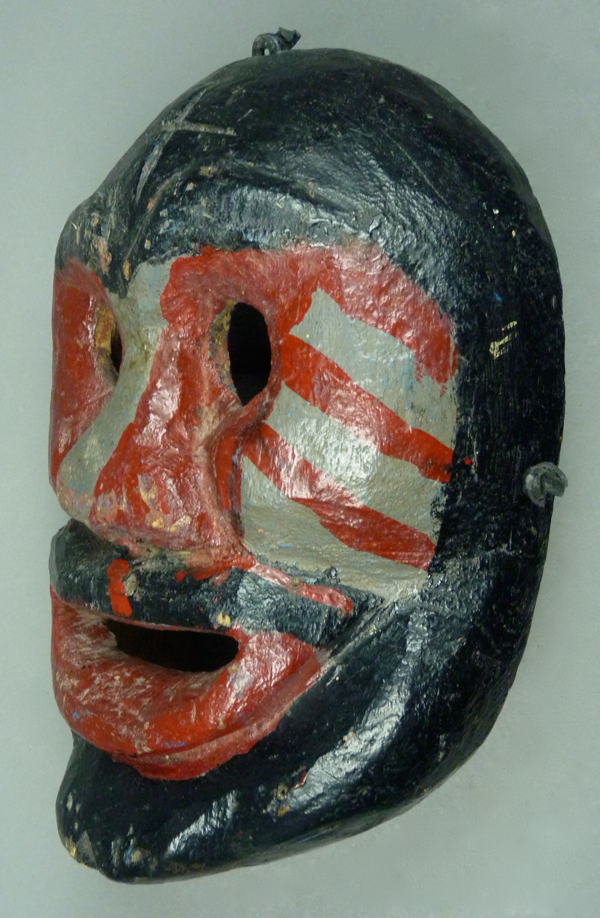

In contrast to the dichotomies raised by the last few masks, regarding the comparison of good versus bad behavior, the next mask illustrates the stereotyping of foreigners and the scaping of otherness, of negating an outsider. This is evidently a mask of an Asian, and probably a person from China, since so many Chinese workers came to the Americas during the 19th century. However, as with many of the other Fariseo masks, this one has been created with unflattering features to emphasize the outsider status of the character.

I purchased this mask specifically because it is such a dramatic example of scapegoating on the basis of race.

I suspect that this mask was originally collected by Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazón, although I purchased it from Robin and Barbara Cleaver. It is 10½ inches tall, 7½ inches wide, and 5 inches deep.

The back of this mask demonstrates moderate wear, but it has probably been scrubbed.

Next week I will present a series of human faced Fariseo masks that apparently personify impulsive and intemperate behavior.

Bryan,

Another great selection of masks. I’m partial to the more primitive, less stylized masks like the ones in the batch that are from Rene Bustamante.

I also purchased a “professor Chanoo Mask from René but it is from Gro. I will try to send it separately as there is no way I can see to attach images in your comment section

Cheers, John Levin

John

At the top, pull down Ask or Tell about a mask and then click on the next prompt, this will accept three photos.

Bryan