This week I will continue to present Fariseo masks from San Luis Potosí (SLP). Today we will examine five human faced masks; two appear to portray drunks/barroom brawlers, another is very similar to the first two, although he lacks their wounds and is otherwise stigmatized by unattractive physical features. The fourth mask depicts a Soldado (soldier), which reminds me of the Fariseos from other states with names like Roveno (Roman soldier) and Centurion (see my post of March 9, 2015). The fifth is a Loco, someone who engages in wild and unpredictable behavior. As I noted in the last post, such masks are based on stereotypes of otherness, targeting those who are in some way different. This week’s masks appear to exemplify individuals notable for their impulsive or aggressive tendencies. I believe that all five of these masks were primarily worn by Fariseos during Semana Santa (Holy Week).

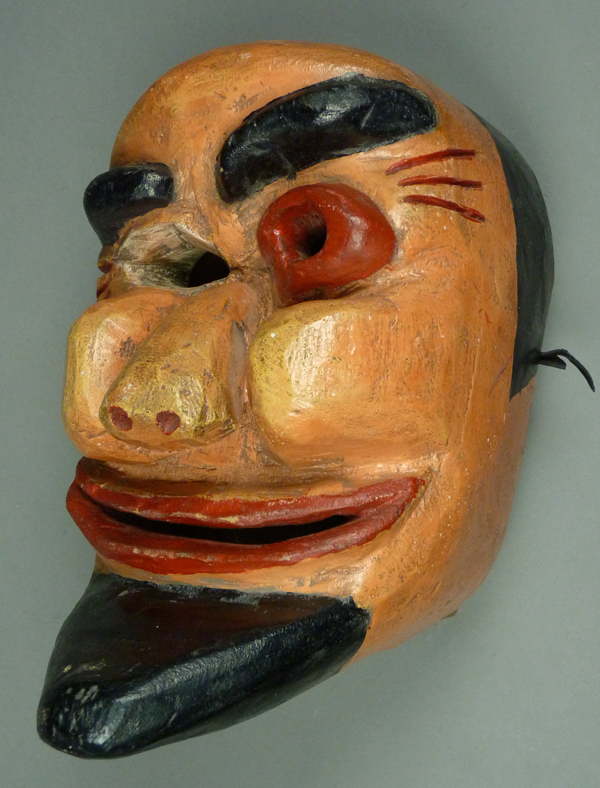

Here is the first of these Fariseo masks. René Bustamante called this the mask of a Golpeado (a person who has been wounded or beaten up); he believed that it was intended for use in Carnaval. I have no doubt that it would serve well in that fiesta. As I discovered in the Sierra de Puebla, there are masks that were specifically created for Carnaval (such as the Onion Woman described in November 17, 2014 post), yet most of the masks used during those revels were borrowed from some other dance. This one was collected in Tancanhuitz, SLP, and René thought it was from the 1940s. If one googles™ “golpeado,” one is shown many photos of wounded faces. Some are of actors in makeup while others are victims of assault.

This is the face of a person with lacerations and a swollen eye, dramatic evidence of a fight. However, the broad smile suggests that this mask does not portray a victim, but a brawler. He could be saying “You should see the other guy!”

This mask is 10 inches tall, 7½ inches wide, and 7½ inches deep.

The back demonstrates staining from heavy use.

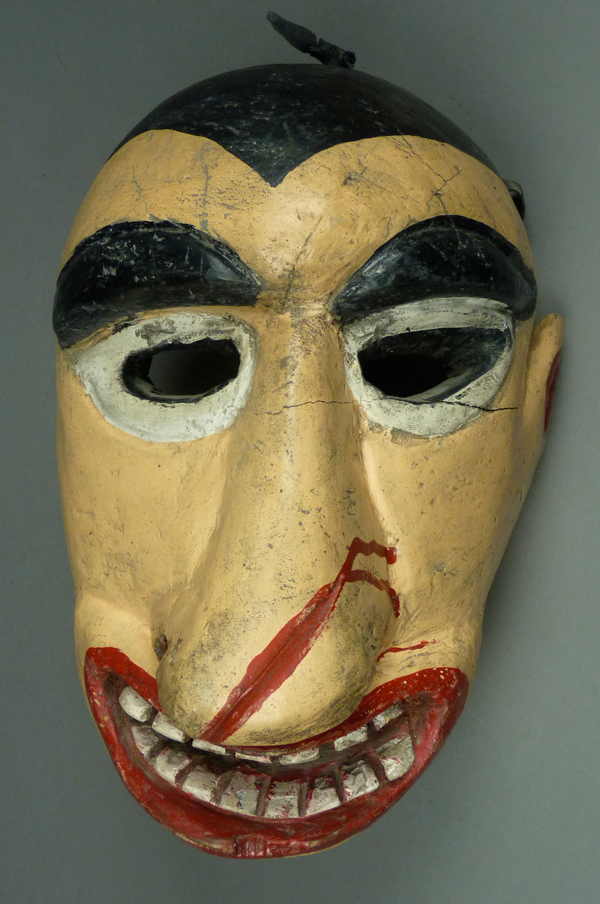

Here is another Golpeado. This mask was collected by Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazón in San Vicente, SLP, and I got it from them in 1996. They described this as a Fariseo mask. Again one sees facial wounds along with a big grin.

This mask is large and vigorously carved.

The mask is 13 inches tall, 9 inches wide, and 7½ inches deep.

The back demonstrates marked staining from use.

In the writings of Janet Esser I encountered an interesting idea. The Roman Catholic missionaries who converted Mexican Indians to Christianity taught that evil or malevolent behavior was ultimately a reflection of ignorance, and more specifically, ignorance of God. Conversely, once one gained a deep and true understanding of God and Christ, the missionaries asked, how would it be possible to engage in evil behavior? The stereotypes conveyed by Fariseo masks can be understand in the context of such teachings.

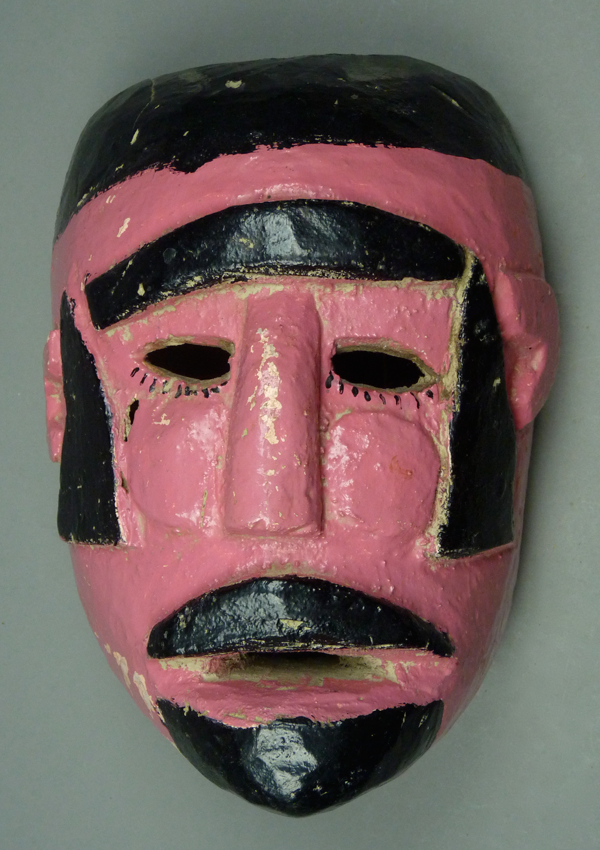

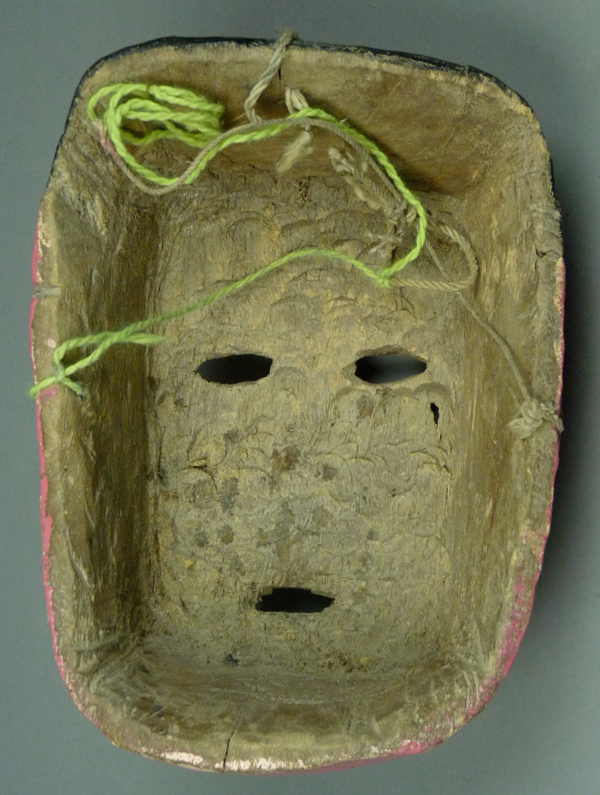

I also purchased the third of these masks from Jaled and Estela. It appears to be by the same hand as the last mask, but lacks signs of injury. Instead we find a vivid but odd looking face with fang-like teeth at the corners of the mouth, but with no teeth between the two fangs.

This is certainly a comic face.

This mask is 11inches tall, 10½ inches wide, and 7 inches deep.

This mask too has marked wear.

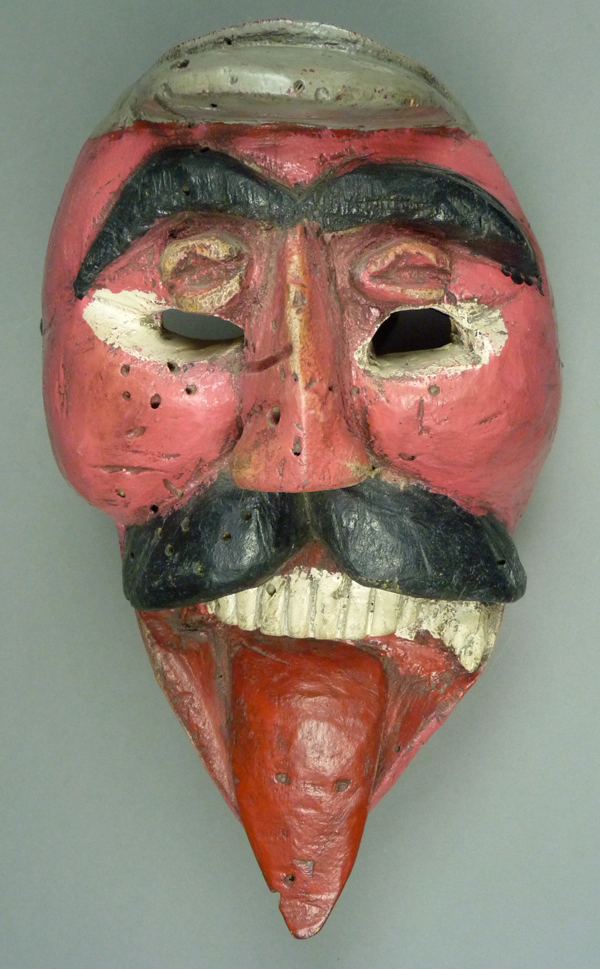

Next we will examine the Soldado. Although René attributed this mask to the Conquest dance, I wonder whether it was intended to be a Fariseo.

This mask is remarkable for the management of the facial hair. The eyebrows (really a unibrow), the sideburns, and the mustache all are carved in relief, while the hair and the goatee are merely painted. There are circular relief carved cheeks as well. In the Conquest dance, as performed in Guerrero and the State of Mexico, the soldiers have red circles painted on their cheeks; one can imagine these cheeks highlighted with darker red paint, although there is no indication that these cheeks were ever any other color. These circles make me think that René may have been correct to attribute this mask to the Conquest dance.

This mask is 9 inches tall, 6¾ inches wide, and 4 inches deep.

The back demonstrates good wear.

The fifth mask, another from René Bustamante, has small eyes shaped like coffee beans, but with a second set of eyes below. All of his other features are also dramatic. His face is misshapen. He is wearing a small gray cap. Like the first mask, this one was collected in Tancanhuitz; René called it El Loco and attributed it to the dances of Carnaval. According to Cassell’s Spanish Dictionary (1960), loco means “madman, fool, insane, crazy, or crackbrained person.” While I do not doubt the utility of such a mask for Carnaval, I see it as primarily a Fariseo mask for use during Holy Week, a “poster child” for the lack of understanding that would permit someone to behave as an enemy of Christ.

The long extended tongue is another remarkable feature. He has a fang on the left side of his mouth, but none on the right.

This mask is 12 inches tall, 7 inches wide, and 5 inches deep.

This is a lopsided mask, with obvious old worm damage to the wood, and marked wear. It is another mask that Reneé thought was from the 1940s.

Next week I will continue this series of posts about Fariseo masks from San Luis Potosí with some that have animal faces. Those are masks that could well have been used during Semana Santa or during Carnaval.