As previously noted, I am always interested in identifying the maker of an attractive but anonymous mask. Sometimes the observed features are merely suggestive of a particular hand, while other details seem to contradict that attribution. On further study, incremental clues may accumulate to a point where the identity of a particular mask’s carver becomes suddenly obvious, or this same accumulation may overturn one’s earlier impressions. In today’s post I will discuss four beautiful Yaqui Pascola masks from my collection that have obvious age, remarkable wear, and mystifying features. I imagine that they date to the 1940s or 1950s, but of course I have only limited data to support this impression. Whether you share my obsession about attribution or not, I am sure that you will be charmed by these masks.

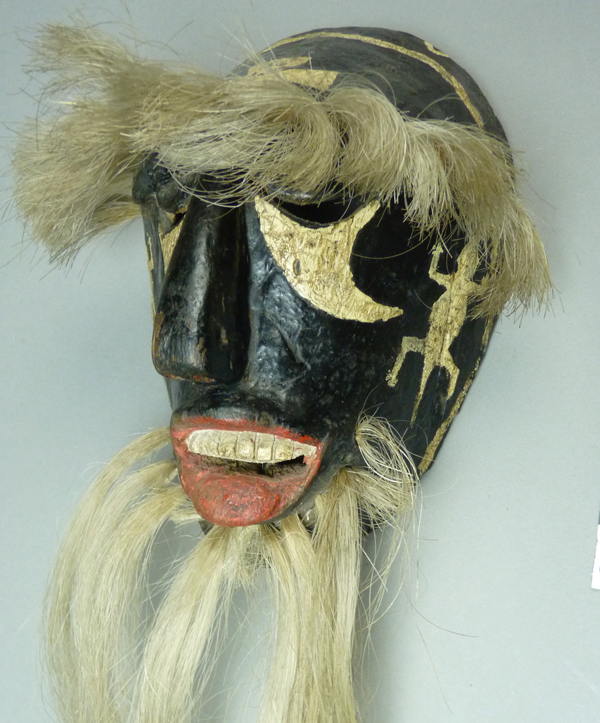

I have pestered my friend Tom Kolaz about these masks and their features for more than a decade. Tom’s response seems like a good place to begin. He notes that these masks are old enough to have been repainted, perhaps more than once, and so some of the features that they have in common may reflect the hand of a later painter rather than that of the original carver. Such a situation might mitigate against my hope to identify the carvers. I acknowledge the validity of his perspective. Nevertheless, because these masks are so beautiful, they haunt me. Here is one of them. I bought this mask from Fred Huntington, a Tucson Indian Arts dealer, in about 1995.

Recently I realized that there is much about this mask to suggest that it was carved by Manuel Centella Escalante, who was one of the greatest of the mid twentieth century Yaqui masters. I wrote about him at length in my posts of December 12, 19, and 26, 2016, and January 2, 2017. Manuel sometimes used these crescent shaped vision slits located under the eyes, and Tom Kolaz pointed out to me that he also made masks with this mouth design, although this is the only time that I have seen him carve both of these features on the same mask. What seemed uncharacteristic for this master was the clumsy nose, which looks more like a hot dog than a human nose. However, there is a similar mask in the collection of the Arizona State Museum and that is one that has not been camouflaged by repainting; it is definitely by Manuel Centella. It has a similar undistinguished nose, along with the same mouth, but it lacks those cresent-shaped vision slits and it doesn’t have those painted lizards. On the other hand, there is another near duplicate in the Heard Museum (Phoenix, Arizona), collected in 1976, that has this plain nose design and even similar lizards.

Centella’s masks often have matching crosses on the forehead and chin. The two crosses on this mask appear to have been repainted, obscuring their original forms. Centella’s rim designs are often outlined with inscribed lines, and they are usually more elaborate than these sketchy triangles, but how many times has this old mask been scraped and repainted? The ASM and Heard examples also have such crudely painted rim designs.

We will see these painted lizards again on the masks that follow, whether flanking the forehead cross or on the cheeks. In this case, the forehead cross and the lizards do seem to be later additions, and/or repainted. This mask is 7 inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

Great age and a heavy history of use are suggested by the staining of the back, an impression that is reinforced by the dirty and frayed strap ( a shoelace). My current impression is that this is definitely a mask by Manuel Centella Escalante, although this was not apparent to me for many years.

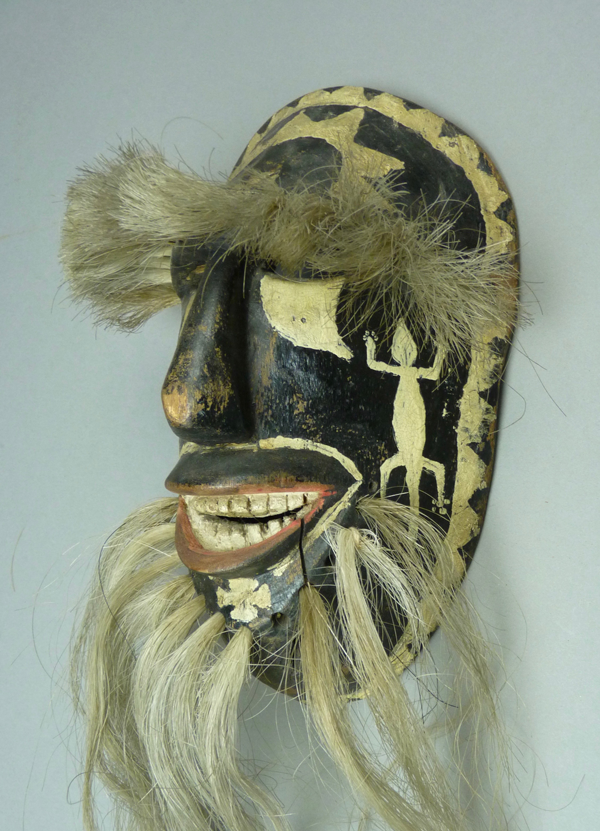

I found a trio of old and worn Yaqui masks in a Zona Rosa shop (Mexico City) in March of 2000. They were said to have been collected together as a set, but the town of their origin was not recorded. All three were decorated with painted lizards. The first of these resembles the last mask in some respects.

We see the same vision slits, the same nose, and similar painted lizards, while the cross is not very different from that on the previous mask. It does not appear that this mask has ever been repainted, and the lizards on the cheeks look like they were painted at the same time as the other decorative elements.

The rim design is again overly simple or crude, compared to many other of Manuel Centella’s Pascola masks.

I particularly like the tongue on this mask.

This mask lacks a chin cross, unlike most of Centella’s masks.

This mask is 6¾ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 3 inches deep.

The back is stained and chipped.

The other human faced mask of the trio from the Zona Rosa looks somewhat different from the last two, but it does have a similar nose, the lizards are exactly like those on the previous mask, and the paint on this mask may or may not be original.

The painted designs on this mask are crudely executed, another common feature of these masks. The design that frames the forehead cross is particularly attractive.

Again we see this crudely shaped nose, along with a handsome snouted mouth, and of course there are the same lizards on the cheeks.

I examined these crosses under a magnifying glass, and saw no incised lines, but such lines could be hidden under this heavy paint.

This mask is 7¾ inches tall, 5 inches wide, and 2½ inches deep.

The back is darkly stained from use.

The lizards on the next mask, which you will see are distinctly unlike those on the last two masks, actually appear to link that mask to another carver, as I will soon explain. This leaves the last two masks (the two human faced masks from the trio) as a possible pair that were carved by the same hand, but whose? I will share two theories, because I am uncertain which one might be correct:

These two masks were carved by Manuel Centella Escalante, and they fall into a group of masks by that carver that are less formal. This group includes the first mask in this post and similar masks in the collections of the Arizona State Museum and the Heard museum.

These two masks were carved by Felipe Buitimea, the identified carver of a mask in a book by James S. Griffith and Felipe S. Molina—Old Men of the Fiesta: An Introduction to the Pascola Arts. The mask appears on page 34 of that book, with this caption, “The mask on the right was made around 1965 by Felipe Buitimea of Vican, Sonora.” I assume that this mask had been collected by Dr. Griffith at that time, but I don’t know whether the information provided with the mask was reliable. As you must know if you have been reading along, wonderful masks are frequently accompanied by misinformation. At any rate, the mask said to by Buitimea has the exact same lizards painted on the cheeks and it has the same sort of nose.

In Mexican Masks, by Donald Cordry (1980, page 58, plate 74) we find a fourth example of this type of mask. It has the very same lizards on the cheeks, the same awkwardly shaped nose, and in its overall design it looks very much like the last mask (#3 in this post). Cordry reported that he purchased this mask in Guaymas, Sonora in 1955. So we find ourselves with four masks that could be reasonably attributed to one or the other of these carvers.

Regarding this ambiguity, I will make one further observation. Apart from the mask in Griffith and Molina’s book, I have never seen a Yaqui Pascola mask that was unambiguously identified as Felipe Buitimea’s. When I examined more than 300 Yaqui masks in the Burns collection, I found none attributed to that name, nor were there any that were in this style. Likewise I found none in the Arizona State Museum collection. We have plenty of evidence for the existence of Manuel Centella as a known carver, while the evidence for Felipe Buitimea is slim. Therefore I think it is more than likely that all four of these masks were actually carved by Manuel Centella Escalante.

The last of the three masks from the alleged dance set depicts a goat.

In addition to the obvious fact that the other masks have human faces while this one represents a goat, there are other differences. The painted lizards look a little different from the others and they flank the forehead cross instead of being located on the cheeks, something one can see on the masks of Beto Matus. We saw this positioning on the very first mask, but in that case the lizards were probably not painted when the mask was new, while the paint on the goat mask looks to be original. Another obvious difference is that the vision openings on the goat mask are round, while the other three masks have crescent or almond shaped openings. The crosses on the forehead and chin are also a little different from the others.

The mouth and tongue are delicately carved.

There is a goat Pascola mask in the collection of the Arizona State Museum that has these three painted stripes down the nose, but that mask has obvious features of Alejandro Reyes Alegria (another mid-century Potam carver), while this mask lacks his other features. On the other hand, here is a photo of the brow of a mask by Beto Matus that is in the collection of Tom Kolaz. Look at the lizards flanking the cross.

The forehead and chin crosses on the goat mask resemble the forehead cross on the Kolaz mask.

The delicacy of this carving does force us to go through a list of the mid-century masters. Already one that has come to mind is Beto Matus. A photo of the back of one of his masks follows that of the mystery goat, for comparison. This goat mask is 7 inches tall, 5¼ inches wide, and 3½ inches deep.

This mask has the same worn appearance that we find on the other three masks, but the design of the back is distinctly different from the others. In fact it looks very much like the backs on masks by Beto Matus. I wonder if Beto was the carver of this goat. I call your attention to a subtle Beto characteristic, that the goat’s open mouth communicates with the interior, but only via a narrow carved slit.

And here is a photo of the back of the Beto Matus mask from the collection of Tom Kolaz. Note the round openings for vision.

The subtle slit that permits air to enter through the mouth is nearly hidden by the strap (string), and the two masks have nearly identical backs. I conclude that the goat mask was probably carved by Beto Matus.

I hope that you have enjoyed looking at these old and very well carved masks. Next week we will look at old and worn masks by another mid-twentieth century master, Daniel Moreno.