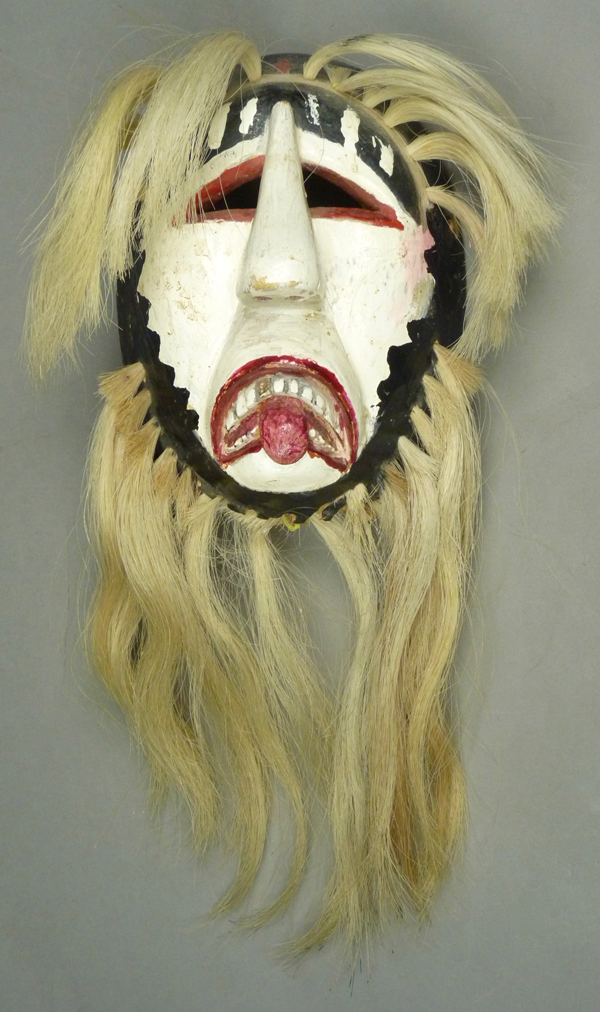

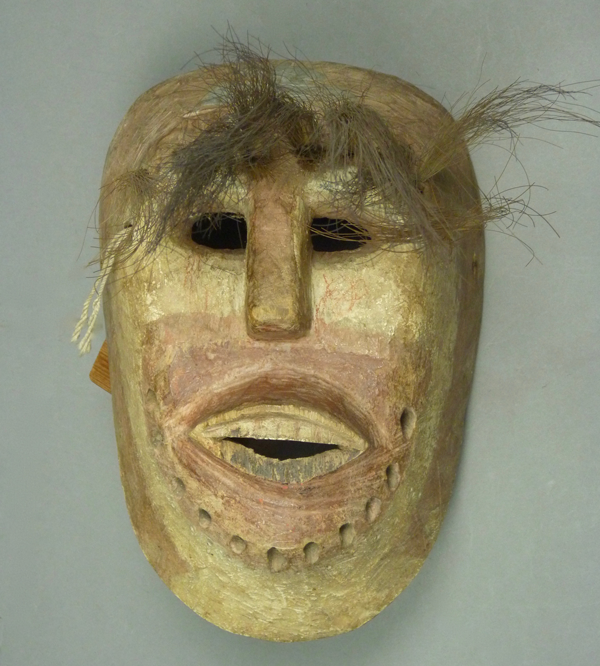

Last week we looked at four Rio Mayo Pascola masks that were carved by Héctor Francisco “Paco” Gámez in the 1980s and 90s, and then they were danced in Mayo fiestas for ten or twenty years, each possibly by just one dancer. This week we will examine five Rio Mayo masks from a parallel tradition, that of made-for sale masks. These too were made by Francisco Gámez, but most of them in a more colorful and less traditional style. They were briefly danced, perhaps for several fiestas, by Pascola dancers in the Sinaloa Mayo towns. This set of five and five more in next week’s post were all collected during the late 1980s by Barney Burns and Mahina Drees, and I traveled west to Tucson to photograph their collection in 2016. Here is a link to an earlier post where I told a little more about Barney and Mahina, in the context of discussion of Yoeme (Yaqui) Pascola masks.

https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=6930#more-6930

I should note that all ten of these masks originally had attached hair bundles to form the brows and beard, but insects have destroyed the hair on many of these masks. On the positive side, the absence of hair makes the details of these masks much easier to see. I didn’t measure any of these masks.

Also I should repeat an observation expressed by Mahina Drees, that some of these masks could have been carved by Serapio Gámez , the father of Francisco Gámez, and she was often uncertain whether a mask was carved by one or the other.

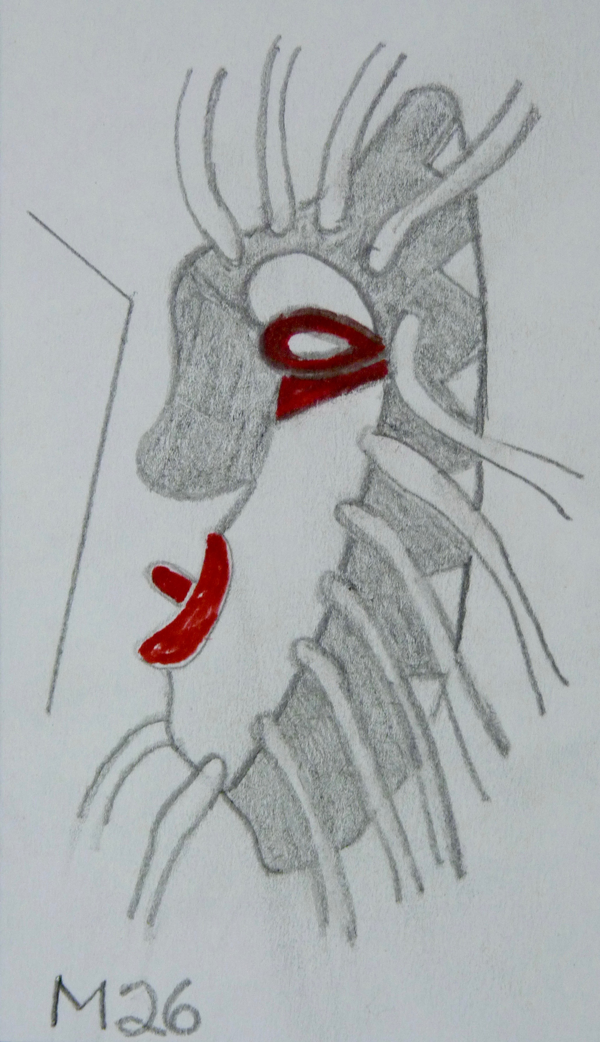

Here is the first of today’s group, a mask with the face of a bird, and with smaller birds flanking the forehead cross. Bird-faced masks are actually very uncommon in the Rio Mayo villages, as human faced masks are the preferred style. Apparently this mask was actually danced by a Mayo Pascola dancer in Sinaloa, where goat-faced masks are the most common style and bird faced masks are slightly less rare. The rest of today’s masks have human faces.

This is quite playful, attractive, and very well carved, isn’t it, although absolutely non-traditional.