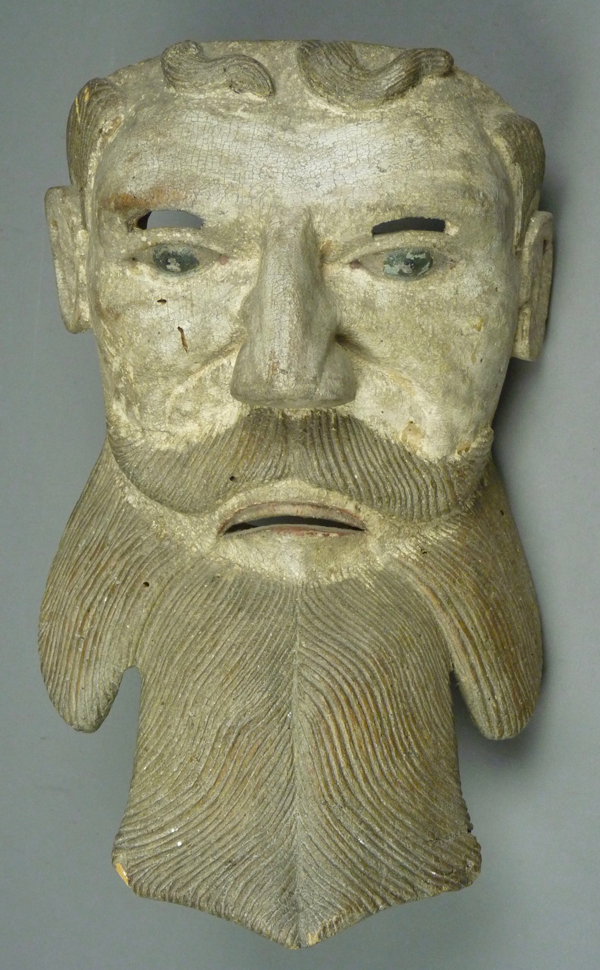

In today’s post I will discuss a single remarkable mask. I purchased this from Robin and Barbara Cleaver in 1995, but they had only recently obtained it from Spencer Throckmorton, and Spencer reported that it was previously owned by a famous 20th century Mexican collector and antiquarian, Raul Kampfer. It appeared to be a mask depicting a Moorish leader or king, perhaps it depicts Pontius Pilate, Herod, or the Emperor Tiberius, and it was probably used in the Moors and Christians dance drama (the typical frowning mouth of a Moor is apparent). What was not known was the place in Mexico where this mask was carved and danced.

Over the last 20 years I have searched through many books, looking for a mask of this unusual appearance, and I have only found one similar example in a dance photo— En El Mundo de la Máscara (page 58, left), “Danzante con máscara de rey, Sierra de Puebla” (dancer wearing a mask of a king). That mask has a single-lobed beard flanked by enormous sagging ears, so that it resembles this one in appearance, or at least more closely than any other mask I have seen. Note that the Sierra de Puebla is conventionally thought to include parts of the Mexican States of Puebla, San Luis Potosí, and Veracruz, but used loosely it can also refer to the Pacific highlands of Guerrero as well. To my eye, this looks like a mask from Guerrero or the State of Mexico, although one can find such finely carved ears in Guerrero or Puebla. Obviously it is very old, and we may never find another that has survived.

The design of this mask is so elaborate. The fancy hair, for example, reminds me of Colonial carved wooden images from Mexico or Guatemala of el Padre Eterno (Eternal Father, or God). But of course it calls such images to mind, because such a refined mask would have necessarily been carved by a santero, drawing on imagery borrowed from images of God and the Saints. Here is an image of God from Guatemala.