In my recent series of posts about La Danza de los Santiagueros I demonstrated how the Indians of Mexico had managed to insert hidden meanings into public dance performances. As James Scott explained in his book, Domination and the Arts of Resistance (Yale University Press, 1990, 1-16), it is common for the less powerful in any society to search for ways to safely complain about felt mistreatment by the more powerful; one solution has been to present the grievance in a disguised form. He calls such a disguised complaint a “hidden transcript.” One of the best documented examples of a Mexican dance drama with a hidden transcript is La Danza de los Tastoanes. Although it is usually rare to find detailed explanations of Mexican Indian dances in English, one can learn a great deal about the Tastoanes dance from the books and articles listed at the end of this post.

In light of what I have just written, here is a riddle—”When does a Mexican mask not represent what it appears to be?” The short answer—”frequently.” A slightly more precise answer is— “when it cloaks a hidden transcript.” In la Danza de los Tastoanes the same dancers wear the same masks in a two act performance, yet they probably portray two different groups of characters, one in each act.

Here is a link to a YouTube™ video of the Tastoanes dance:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JdmnpBErj7g

And here is another link, this one about how these leather Tastoane masks are made in Jocotán, Jalisco.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2neuiXeMkE

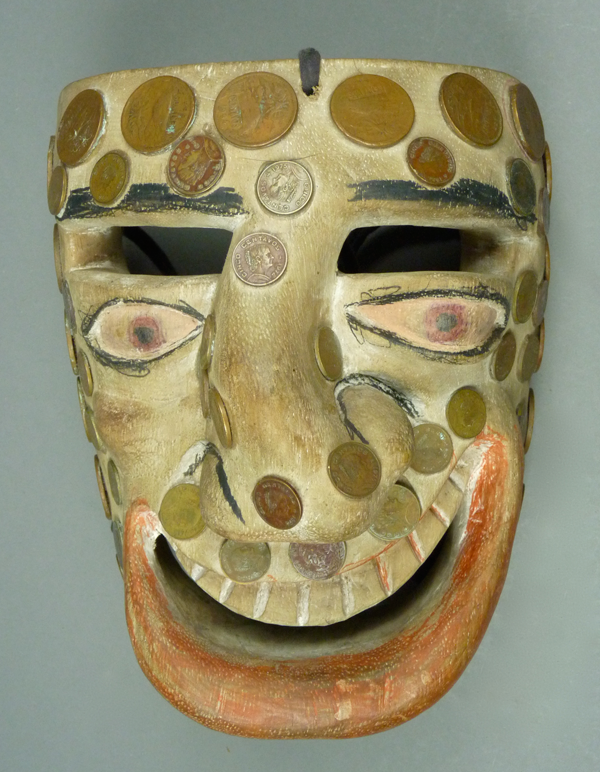

In this post I will begin with two traditional Tastoanes masks from San Juan Ocotán (Ocotán and Jocotán are neighboring villages), a town in the Municipio (county) of Zapopan, Jalisco, that I obtained from Jaled Muyaes and Estela Ogazon in 1997 . These are made from leather with attached wooden features and wigs of animal hair. Here is the first of these masks.

This Tastoane mask has the face of a dog. The mask is made of leather, and a carved wooden element provides the dog’s nose and open mouth. This is the standard method for the construction of such masks in villages near Guadalajara such as Jocotán and Ocotán. The hair appears to be horse tail.

Pan Bimbo™ (Bimbo Bread) is a popular brand of mass produced bread in Mexico. On the right side of this mask the dancer has personalized his mask with a small copy of the logo for that bakery, a comic figure wearing a baker’s hat. At the top one sees another such comic element, a pair of footprints.

Continue Reading →